Social Worker or AR-15? Portland Struggles Over How to Respond to People in Mental Health Crisis

As Portland weighs expansion of an alternative crisis-response program, new data from a MindSite News-Medill investigation shows police often deploy force on residents who are unhoused or grappling with mental illness.

This story was produced by MindSite News, an independent, nonprofit journalism site focused on mental health. Get a roundup of mental health news in your in-box by signing up for the MindSite News Daily newsletter here.

This story is the latest installment of Fateful Encounters, an ongoing investigative collaboration between MindSite News, the Medill Investigative Lab-Chicago at Northwestern University and other media outlets exploring police response to mental health crises. This work is generously supported by the Sozosei Foundation.

On a fateful morning in April 2021, Portland police responded to a 911 call about a man holding a gun in Lents Park, a suburban park where unhoused people often sleep in tent encampments or in the parking lot. Within four minutes, Robert Delgado was dead, fatally shot with an AR-15 by an officer trained to respond to mental health calls.

Witnesses agree that Delgado was agitated and pacing erratically back and forth, drawing the gun and doing James Bond-type moves, but accounts of the killing differ. A witness said Delgado was unarmed and had his hands up as police approached. Two officers who fired at him—one with an AR-15 and the other with a less-than-lethal projectile launcher—said he pointed what looked like a handgun at them.

An Airsoft gun—a toy weapon that shoots plastic bullets but resembles a real firearm—was found near him after the shooting. Unhoused people often carry such “replica” guns or BB guns for protection, advocates say.

High rates of police use of force

Delgado was one of 22 people in Portland with mental health issues who were killed by police between 2004 and 2019—eight of them shot by AR-15s—according to a city review of police use of force. Another 15 were shot but survived.

A separate MindSite News-Medill Investigative Lab-Chicago analysis of police department data shows that another 880 were subject to non-lethal force while experiencing a mental health crisis between 2017 and the fall of 2024. Almost 40 percent of them—including Delgado—were unhoused, according to the department’s public records dashboard. Nationally, research suggests that about a quarter of unhoused individuals have a diagnosable mental health disorder, which amplifies their vulnerability during police encounters.

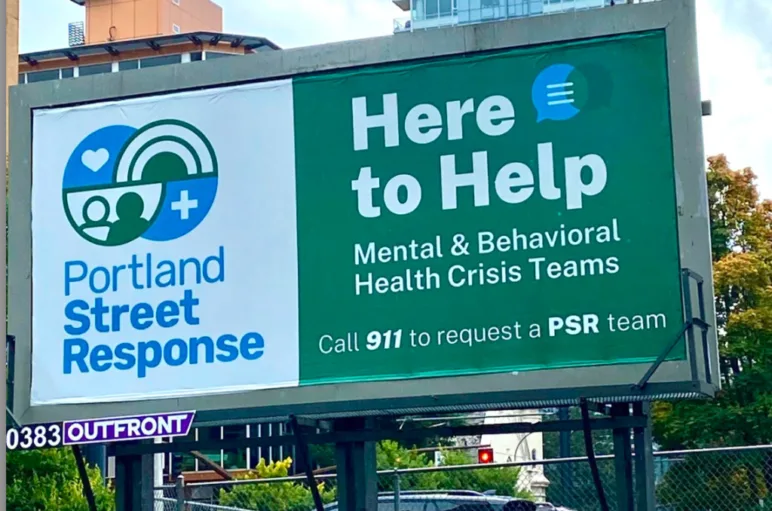

The high rate of force is happening in a city that, since 2021, has been operating a program that deploys clinicians to respond to mental health crises instead of police. The well-regarded program, Portland Street Response, will increase its hours of operation if a budget increase proposed by the mayor is approved by the city council in the coming weeks.

In Portland, as in other cities, officers who use force—including fatal force—against people experiencing a mental health crisis rarely face repercussions. A grand jury would later say the shooting of Delgado was justified. The officer who shot him, Zachary Delong, was promoted to detective 11 months after Delgado’s killing. He remains on the force.

After the shooting, a crowd gathered around the park and began throwing things at a group of officers who remained at the park and “feasted on pizza” while Delgado’s body lay in the park, according to an ongoing lawsuit filed by his family.

Portland police spokesperson Sgt. Kevin Allen declined to discuss Delgado’s killing and Officer DeLong’s involvement because “it is a personnel matter,” he wrote in an email. “But I can say that the Bureau does a complete and thorough review of the performance and discipline history when deciding whether to promote” an officer.

When asked about the high rates of police use of force—including fatal force—used against unhoused and mentally ill people in Portland, Allen had more to say.

“Police officers in Portland and nationwide are called to serve our communities from all walks of life, including those who are struggling with poverty, mental illness, and addiction,” he wrote. “These populations are victimized at disproportionate rates and we aim to serve them as completely as we do any other community member. When force is used by police, our policies on use of force reporting aim to make sure that every use of force is scrutinized and reviewed. Officers are also coached and counseled by their supervisors throughout their careers. We are a learning organization at every level and always working to improve.”

Policing the Vulnerable

Portland’s housing and drug crisis has led to a growing unhoused population and large tent encampments like the one in Lents Park where Delgado was shot. He had sought mental health treatment multiple times before the shooting and spent time in the hospital after being attacked by other unhoused people, according to Oregon Public Broadcasting.

“Our addiction service systems and our mental health service systems were woefully underbuilt,” Jason Renaud, a board member for the Mental Health Association of Portland, told MindSite News. “Someone like Robert Delgado can bounce around not getting services for years and years. If he had services, he may not have been in that park.”

Oregon, like other states, began closing state psychiatric hospitals in the 1960s, with the idea of shifting resources to community-based care and housing. But those services failed to keep pace as the number of people rotating in and out of homelessness rose over time.

Adding to the problem in recent years is the worsening addiction crisis as fentanyl and methamphetamine have exploded into the street-drug supply. In Portland, the result has been a complex mix of social crises which police are ill-prepared to address.

Between 2004 and 2010, Portland police killed eight people in the midst of mental health crises, according to records released in the aftermath of a lawsuit filed in 2012 by the U.S Department of Justice against the Portland Police Bureau. The DOJ’s 18-month investigation found that Portland police had engaged in a “pattern or practice” of using excessive force against people with mental illness and led to an agreement with the city to reform police practices.

In addition to the eight fatal shootings, the DOJ’s investigation found a disproportionate use of tasers and other “less lethal” weapons on people in mental distress. The settlement agreement reached in 2014 and later amended with new additions mandated a review of police use-of-force policies, the creation of a crisis intervention team designed to handle mental health-related calls, more mental health-related training for officers, the use of body-worn cameras, an early warning system to flag abusive officers and the creation of a new police oversight board. In March, applications opened for the 21-member board, which will be appointed by the city council.

The DOJ settlement also required the hiring of a compliance officer/community liaison to monitor the department’s adherence to the DOJ settlement agreement. Last year, then-compliance officer Tom Christoff found the city was meeting the terms of the agreement related to crisis response. But police watchdog groups including Portland Copwatch say the department is still using force too often, including against unhoused people. Christoff told MindSite News that the finding of compliance doesn’t mean all problems are solved.

“If anyone has taken the settlement agreement to be that we’re creating a perfect department, that’s a fundamental misunderstanding,” said Christoff, who also previously served as a monitor overseeing a consent decree between Chicago Police and the state of Illinois.

Allen said all officers are required to take Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training, a curriculum used nationally to help officers respond to mental health crises, and can also volunteer for enhanced CIT training to further “identify risks during a behavioral crisis, utilize crisis communication techniques to help de-escalate a person in crisis, and have knowledge of available community resources.”

According to data obtained through public records requests, in 2023, 146 officers—almost 20 percent of the force—had taken part in the enhanced training, including Zachary DeLong, who received his enhanced CIT certification before fatally shooting Robert Delgado.

The department also operates a behavioral health unit, which “offers access to treatment, housing and wrap-around services as an alternative to continued criminality and incarceration,” Allen wrote.

Fatalities and Disparities

MindSite News’ analysis of public records found that in Portland, as across the nation, Black men are disproportionately likely to experience force from police during a mental health crisis. In Portland, Black people constitute 6 percent of the population but were the subjects of more than 20 percent of all mental health-related use of force reports in the city, according to police data from 2017 through April 2025.

“I cannot say why there are disparities. There are racial disparities in many areas of our society, from crime victimization to educational success to medical outcomes.”

Portland Police Spokesperson Sgt. Kevin Allen

Black people also make up a quarter of all arrests of people with mental health issues during use-of-force incidents, and more than a quarter of all unhoused people arrested in those situations.

“I cannot say why there are disparities as compared to census demographics,” said Allen, the Portland Police Bureau spokesperson. “There are racial disparities in many areas of our society, from crime victimization to educational success to medical outcomes.”

The killing of a Black man named Aaron Campbell in 2010 was one of the triggers for the DOJ investigation. Campbell’s girlfriend called the police when he was experiencing suicidal ideation; the dispatcher told responders that he was armed. Campbell turned out to be unarmed, yet the police who responded shot him with an AR-15.

Even after the DOJ settlement, police shot people in crisis:

- On Feb. 9, 2017, Don Perkins, a homeless man experiencing a mental health crisis, called 911. He was shot with an AR-15 by Bradley Clark, an ECIT-trained officer, after Clark spotted a weapon which turned out to be a harmless replica handgun. Perkins survived and settled his lawsuit for $60,000, an amount that doesn’t cover the medical bills he listed in his legal filings.

Greg Townley, researcher and co-founder of Portland State University’s Homelessness Research & Action Collaborative, said unhoused people like Perkins and Delgado sometimes carry replica handguns because they are often subjected to crime and violence.

“There are many understandable reasons why people would be carrying a replica if they were at risk of being harmed,” said Townley. - On Jan. 6, 2019, Andre Catrel Gladen was fatally shot by Officer Consider Vosu, after a 911 call reporting that Gladen was trespassing. Gladen was Black and legally blind, and family members said he struggled with schizophrenia and was taking medication.

When Officer Vosu spotted Gladen, he deployed his taser and then fired his gun. None of the officers who responded to the call were ECIT-trained; an ECIT-trained officer showed up only after Gladen had been killed. - On June 24, 2021, Micheal Townsend called 911 while experiencing a mental health crisis in a motel, and asked for help from police. According to the Portland Police Bureau’s investigative files, “he was feeling suicidal and high on methamphetamine.”

During the call, he disclosed that he had a screwdriver. When officers Curtis Brown and Brett Emmons arrived on the scene, Townsend agreed to go to the hospital for a mental health evaluation. But he didn’t respond when police asked to check him for weapons, and when he advanced toward the officer with his screwdriver, Brown fired his weapon. Townsend died from the gunshot wound.

Ronald Frashour, who killed Aaron Campbell, was fired but then reinstated in 2016 based on a state appeals court decision. Officer Clark, who shot Don Perkins, is still on the force. So are officers Vosu, who killed Andre Catrel Galden, and Brown, who shot Micheal Townsend.

Townsend’s sister, Rachel Steven, whose family filed a wrongful death suit against the city, told Oregon Public Broadcasting: “Michael reached out… The wrong people responded. This was a very serious call of someone who was scared, needed help and expressed those things.”

“I can never get my brother back,” she concluded. “All I can do is focus on making the world a safer place, a better place, for people like him.”

A Different Response

City officials launched Portland Street Response (PSR) in 2021 to create an alternative method for responding to mental health crises that doesn’t put police front and center. Many cities nationwide have instituted such programs in recent years, especially after the 2020 police killing of George Floyd. The Portland program has extensive community support, including from the police department.

“Every day I hear on the radio officers asking for PSR to come help someone who needs it,” said Sergeant Allen. “We know that police are not always the best responders for certain situations and we believe strongly in this initiative.”

Portland Street Response teams, made up of a mental health counselor and a paramedic, are dispatched by 911 when a caller describes a person in crisis – as long as the person is unarmed and not experiencing suicidal ideation. Previously the teams could only serve people outdoors, and they could not transport people. A 2022 evaluation found that 68 percent of PSR’s calls served people who were unhoused.

In March, Mayor Keith Wilson called PSR “a success story” and announced that the teams can now enter businesses and government buildings and transport people to care with their consent. The new policy also allows police to call PSR to join them at a scene, even if the initial call didn’t meet the criteria for PSR to respond alone.

Last year the program’s budget was cut from $10.1 million to $7.4 million, though then-Mayor Ted Wheeler noted it was the first time a permanent funding stream was instituted rather than grant funding.

For next fiscal year, Wilson proposes increasing the program’s budget to $10.1 million, adding 14 full-time staff and expanding program hours. The city previously estimated that round-the-clock operations would require 68 staff and $10.6 million a year. The mayor released his proposed budget May 5, and public meetings are being held in coming days.

The program currently operates only from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. daily, though many crises happen overnight. The limited hours keep it from qualifying for Medicaid funding, which requires 24-hour operations, noted Greg Townley, the Portland State researcher who evaluated the program on behalf of the city.

On the day of the budget hearing last May, supporters of the program rallied outside city hall wearing blue and yellow to demand expanded funding. Activist Andrés Oswill called it “a critical part of our emergency response system.”

When MindSite News visited the program last May, the team started their morning with roll call in the fire house, their mobile response vans parked outside. The mood was somber as the group reflected on one of their regular clients, who had passed away the day before.

A call came in from a homeowner who only visits her residence occasionally. A man was camping out on her porch; he thought he owned the home and had lost his keys. PSR does not take calls inside private residences, but a porch is a reasonable middle ground.

The team slowly approached the porch, making sure that they had a safe and clear pathway for exit. The mental health counselor stepped up on the stairs and kneeled down to talk with the client.

“What about this place feels safe to you?” she asked. “Is there someone from your family that you would like to talk to?”

The man declined to leave, the team thanked the client for engaging in the conversation and got up. As they left, with the client still ensconced on the porch, another unhoused person nearby sarcastically asked, “Do you actually help people?”

For the street response team, every encounter can be challenging, but team members say they strive to respond with compassion, build rapport and help people get the services they need.

“What I really appreciate about our teammates is that everybody’s so empathetic,” Heather Weitman, a community health supervisor, told MindSite News. “For some of our folks, we might be the only people that care.”

Team members don’t have the power to order anyone into treatment, but the program does offer follow-up services to people after their initial encounter. Weitman said the team assigns cases to peer specialists and community health workers who provide social and emotional support, help coordinate care and refer people for housing and other services. As of March, team members can also transport clients to services including shelters, resource centers, addiction treatment and sobering centers and food pantries.

Members of the street response team may be better equipped than police to respond to unhoused people who are on edge, Townley said, because “police may enter that interaction primed to be on guard or to be vigilant against what they perceive could be someone that they think is going to be going to act erratically.”

Portland Street Response receives the highest volumes of crisis calls from Chinatown, where the city’s interwoven crises of substance use, homelessness and mental health concerns visibly intersect and where streets like Burnside Avenue are lined with dozens of tents.

“It’s always been a place where people have been imperiled,” said Kaia Sand, the former director of Street Roots, a newspaper that is sold by unhoused people and acts as their advocates. Sand said her own grandmother experienced homelessness in Chinatown in the 1940s.

Jim McRae, an avid supporter of the Portland Street Response program, used to sell copies of Street Roots in this area before he passed away in 2021 from natural causes, Sand said. He struggled with addiction and mental health, and Sand sometimes encountered him in an unstable state. When she did, she simply called out his first name—“Jim!”—and it would help him focus.

“When my brain itches,” McRae told her, “instead of a badge and a gun, I need a calm and soothing voice.”

Correction: Due to an editing error, the story misidentified the first name of the officer who shot and killed Robert Delgado. It has been updated with the correct name, Zachary DeLong.