Political Report

With New Law, Oregon Joins Wave of States Restricting or Halting the Death Penalty

Senate Bill 1013 is not retroactive, but Governor Kate Brown has the power to commute death sentences.

Senate Bill 1013 is not retroactive, but Governor Brown has the power to commute death sentences.

Movement is building against the death penalty at the state level, even as the Trump Administration calls for expanding its use and prepares to restart federal executions.

Oregon became the latest state to act against it last week when Governor Kate Brown signed Senate Bill 1013, which considerably narrows the range of capital offenses.

The reform does not abolish the death penalty, which is inscribed in the state Constitution and so can only be eliminated by referendum. But the legislature circumvented that requirement by redefining “aggravated murder” (the only category eligible for the death penalty in Oregon) and removing most circumstances that currently warrant the “aggravated” moniker.

“The concept of this bill is to close the front door to the death penalty,” said Lynn Strand, the chairperson of Oregonians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty (OADP). Strand expects the law to be “quite effective” at stopping new death sentences and she called it “a giant step.”

“But it does not address what you do with the back door,” she added.

Indeed SB 1013 is not retroactive. It leaves 30 people on death row, largely for crimes that are not capital offenses under the new law, according to Jeffrey Ellis, an attorney with the Oregon Capital Resource Counsel. That means that the state is now reserving an incommensurably higher punishment—death rather than life—for some people, based on the date of their crime.

The governor has the authority to commute existing death sentences. In explaining her support for SB 1013, Brown called the death penalty “immoral” and “dysfunctional.” These are adjectives that apply to past sentences as much as to new ones. But she has yet to publicly signal whether she is considering commutations. Her office did not answer a request for comment.

“Governor Brown should recognize that this is a failed public policy, and she has the power that others do not to address the wastefulness and the ineffectiveness of the death penalty,” Alice Lundell of the Oregon Justice Resource Center, told me, pointing to a study funded by her group. “Commuting the row… would allow those resources and people’s time to be diverted to things that will make a lot more difference to public safety.”

Representative Mitch Greenlick, whose early version of this bill was retroactive, also told me that he hopes the governor revisits this issue. “It would be rational to commute their sentences,” he said. “We just can’t afford to keep doing what we’re doing.”

Oregon does have a moratorium on executions. It was imposed by John Kitzhaber, Brown’s predecessor. Brown has maintained it in place since taking office in 2015.

The moratorium is important, but it is insufficient to end the death penalty’s moral and financial costs, and to remove its threat from a prosecutor’s arsenal of tools. It could also be lifted by a future governor. “The moratorium stops executions,” Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, told the Sacramanto Bee about California’s in July. “It doesn’t stop the machinery of death from moving forward.”

Oregon law specified 19 circumstances that label a murder “aggravated.” SB 1013 shrinks that list to the murder of a child under 14, a murder committed by someone who is already in prison, a terrorist act that kills more than two people, and the murder of law enforcement officers.

In addition, jurors will no longer be asked to judge a person’s “future dangerousness” when weighing a death sentence.

These changes are leading prosecutors to drop their plan to seek the death penalty in a criminal case underway in Malheur County. Some prosecutors, such as District Attorney Patty Perlow of populous Lane County (home of Eugene), fought the bill.

While Perlow is a Democrat, SB 1013 was largely carried by her party. 48 of 56 Democratic lawmakers voted for it, while only 3 Republicans (Dennis Linthicum, Ron Noble, and Duane Stark) did so. That’s a far cry from the comparatively high level of support for abolition from Republicans in New Hampshire and Wyoming earlier this year.

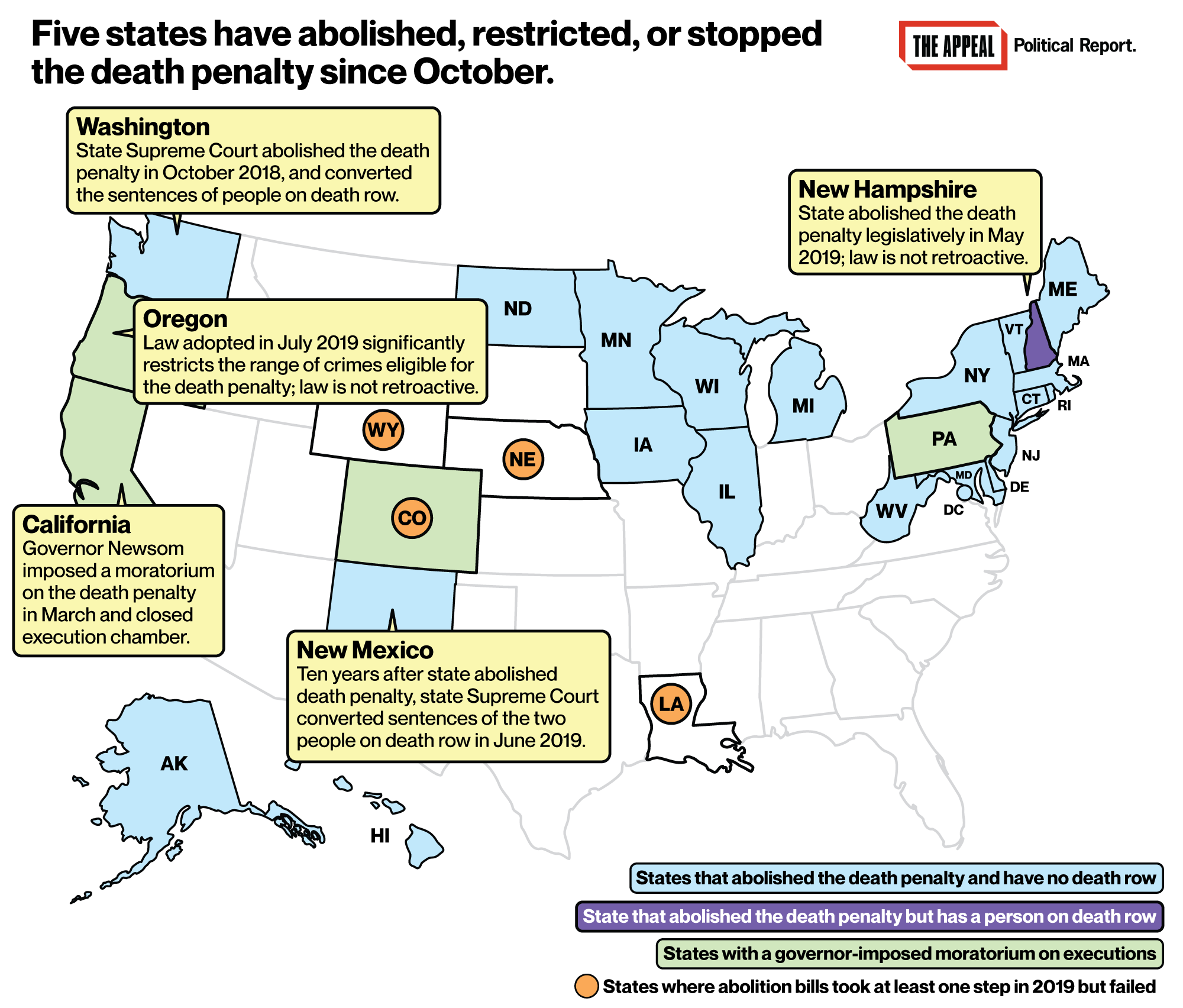

Oregon is the fifth state to restrict, halt, or abolish capital punishment over the last 10 months.

In October, Washington State’s Supreme Court abolished it and also commuted the sentences of all eight people on death row. Then, California Governor Gavin Newsom imposed a moratorium on executions in March; the New Hampshire legislature abolished the death penalty in May; and the New Mexico Supreme Court commuted the sentences of the only two people on death row there in June, a decade after the state abolished the death penalty for new crimes.

New Mexico’s decision leaves New Hampshire as the only state to abolish the death penalty but still have someone on death row.

Death penalty opponents are now actively planning their next moves in Colorado, Pennsylvania, and Wyoming. At the county level, people have successfully run for prosecutor on a promise to not seek the death penalty, and capital punishment looms large in other local elections this fall.

Oregon is also not done with this issue.

Beyond the governor’s powers, lawmakers can revisit the issues of retroactivity or abolition in their next legislative session. OADP will keep demanding a ballot measure on repealing the death penalty “in the next few years,” Strand vowed. Greenlick, the state representative, added that he thought it was “inevitable” that the legislature would organize a referendum in such a timeframe.