Political Report

Wisconsin is Voting For Its D.A.s, But Democracy Is Not On The Ballot

Nearly all of its 71 DA elections feature a candidate running unopposed. Once again, voters won’t have a say over the shape of prosecution and criminal justice.

Nearly all of the state’s 71 DA elections feature a candidate who is running unopposed. Once again, voters won’t have a say over changing the shape of prosecution and criminal justice.

When it comes to prosecutorial elections, expectations of whether anyone is running are low from the start. Incumbents and their hand-picked heirs often skate by with no opponent, and the carceral mindset that dominates these offices perdures unchallenged. It feels like a win for democracy when so much as half of a state’s elections draw multiple candidates.

Even against that backdrop, Wisconsin, which holds its primaries today, manages to stand out for its failure to make local elections count, and to take district attorneys’ vast powers seriously.

In 65 of 71 DA races this year (92 percent), there is no more than one candidate. Sixty-two feature incumbents who are running unopposed.

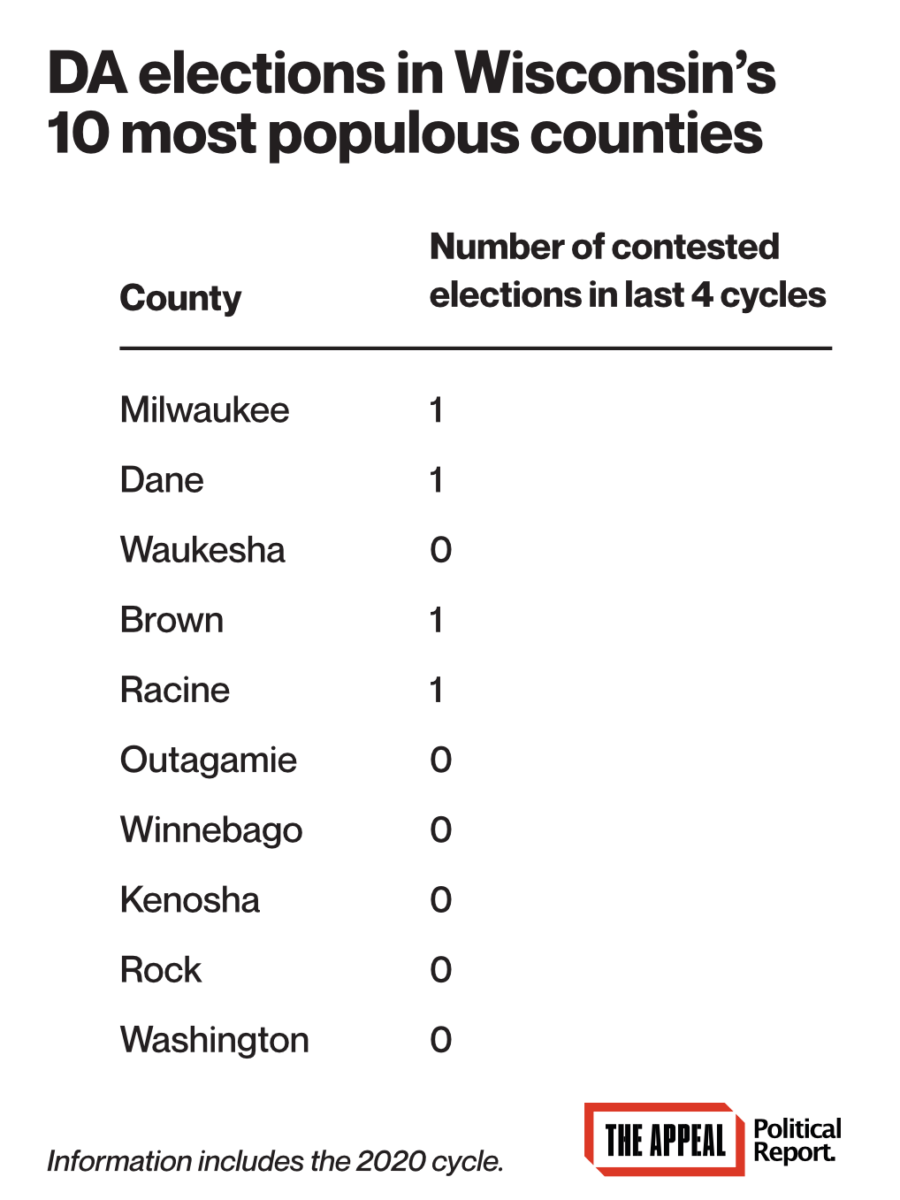

In all of Wisconsin’s 10 most populous counties, the incumbent DAs are running unopposed.

They will secure four-year terms without having to account for practices that have fueled mass incarceration and racial inequality. Advocates point to the continued marijuana prosecutions happening throughout Wisconsin, and to the frequency with which people are incarcerated for violating the stringent conditions of their probation or parole, as policies that these elections are failing to confront.

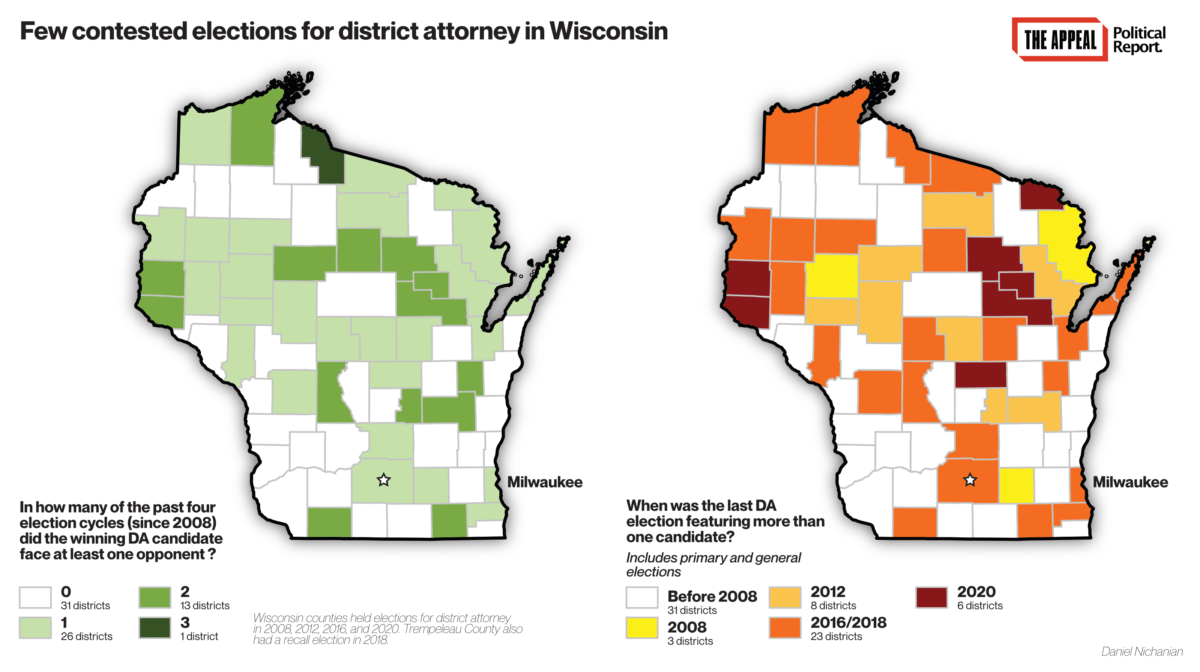

This is a longstanding pattern, an Appeal: Political Report analysis shows. Over the past four DA election cycles (2008, 2012, 2016, and 2020), four of the 10 most populous counties have held a contested DA race once. The six others never have. Similarly, across all Wisconsin counties, 80 percent have held either zero or one contested DA race since 2008.

“I’m just an advocate for democracy,” said Molly Collins, advocacy director at the ACLU of Wisconsin. “Even if I really like them, I think they should have to fight for their seat and respond to voters.” She added that some Wisconsin DAs may be “well-intentioned,” but that she doesn’t see any of them as “doing enough” in the face of the state’s incarceration crisis.

“We have massive amounts of people in prison, we have massive amounts of people on supervision in the community,” she said. “And a lot of that is because of prosecutors’ decisions.”

—

To a greater extent than in most states, incarceration in Wisconsin is fueled by revocations of supervision over violations of probation or parole conditions. For example, failing a treatment program can land people back in jail. Probation and parole terms also last longer in Wisconsin than the national average.

Elsewhere in the country, promises to reduce incarceration over such violations have been a basic staple of progressive candidates’ platforms for DA. “If I watch you for 24 hours a day, seven days a week, within one week, you probably committed reckless driving if you were driving, you may have thrown a piece of paper on the floor,” Buta Biberaj, a defense attorney who ran for prosecutor (and won) in Virginia last year, told me during her campaign. “With those little minor things, I’m going to end up violating you on your probation. I’m going to put you back into the system, and put you back into the system, and put you back into the system.”

Some Wisconsin DAs have argued for supervision reform. But the dearth of candidates running for these offices is robbing advocates of a crucial arena to press for accountability and to force a broader reckoning on what a bold overhaul of this system would look like.

Marijuana—a basic focus of progressive campaigns around the country, as many candidates are pledging to not prosecute marijuana-related offenses—is one example of Wisconsin prosecutors’ reluctance to emulate the bolder reforms now adopted by DA offices elsewhere.

According to the Wisconsin Justice Initiative Inc. (WJI), every county still charges people for marijuana-related offenses. These prosecutions are marked by wide racial disparities, especially in Dane County (Madison) and Milwaukee County. Most people charged in these two counties are Black, even though African Americans make up only 5 percent of the population in Dane County and 27 percent in Milwaukee County. In 2019, by comparison, Baltimore’s chief prosecutor cited the “crisis of disparate treatment of Black people for marijuana possession” to explain why she would stop charging marijuana possession, regardless of quantity.

“This is a system that’s affecting people’s lives, and the DA plays a central role,” said Gretchen Schuldt, executive director of the WJI. Schuldt would like prosecutors to stop charging “petty offenses” that balloon the criminal legal system.

Adam Plotkin, legislative liaison for the office of the state public defender, wants to reduce the system’s scope. “We overcriminalize stuff that is better treated as a health emergency. We expect that if we lock someone up who has a health disorder, after a set period of time we’re going to release them and we’re surprised when they fail on re-entry,” he told me. “It comes down to the fundamental discretion that prosecutors have. They have 100 percent liberty to bring or not bring charges.”

Collins agrees. “The DA could interrupt that by just saying we’re not prosecuting anybody for simple drug possession,” she said.

In 2018, Boston elected a DA who ran on a platform of not prosecuting drug possession (beyond marijuana). Last month, in Austin, Texas, an advocate ousted the incumbent DA on a promise of not charging the possession or sale of low levels of any drug. Each of these victorious candidates made the case that substance use should be treated as a public health issue, not as a criminal one.

Wisconsin’s DA races can spark no such debate as long as (almost) no challenger is on the ballot.

—

“Will anyone run for district attorney in Wisconsin?” I had asked in late 2018, in an analysis of the state’s past patterns. In my 2018 analysis, I noted that the majority of Wisconsin counties had held no contested DA race this decade. “Let’s change this in 2020,” the head of the state’s Democratic Party tweeted in 2019 in response to that analysis. But the state will now have to wait until at least 2024 to modify this dynamic.

The only contested elections this year are in counties that, combined, comprise about 4 percent of Wisconsinites: Florence, Langlade, Menominee and Shawano (Wisconsin’s only counties to elect a joint DA), Pierce, St. Croix, and Waushara.

State advocates are unsure what, if anything, makes Wisconsin even more inhospitable to DA races than already disastrous national standards. “Any job in government service in Wisconsin right now is very difficult,” Schuldt offered. “Wisconsin has devalued its public servants so much.”

Others mentioned more universal hurdles, including insufficient public attention, which makes electoral challenges more difficult, and the fear felt by some prospective challengers that they may jeopardize their legal careers by defying their county’s chief prosecutor.

“If they run against an incumbent DA and are not successful, will they have angered all the people who they have to practice in front of now?” asked Plotkin.

Wisconsin’s landscape may look even more anomalous by 2024 if DA politics continue to shift nationwide, and if demands to shrink the criminal legal system’s funding gain more visibility. Perhaps that accelerating bifurcation also means that more people will be watching.