Political Report

Where Are the (Reform) Candidates in Ohio?

Few Ohio elections feature candidates talking of criminal justice reform, with some notable exceptions such as in Cincinnati. Some activists are pressing ahead through other organizing.

Few of Ohio’s local elections feature candidates focused on criminal justice reform, with notable exceptions such as in Cincinnati. Some activists are pressing ahead through other organizing.

Ohio’s criminal legal system lays claim to many distinctions. It has the nation’s fourth highest rate of people under correctional control, due to an exceptionally large number of people on probation. Ohio is one of the likeliest states to sentence someone to death. And its prosecutors have been among the country’s most aggressive in filing homicide charges in the wake of overdoses as a punitive response to the opioid crisis.

The state’s 2020 elections for prosecutor and sheriff, though, provide few openings for voters who desire to change this status-quo. Few candidates are running for these offices, and fewer still are focusing on issues pertaining to criminal justice reform.

Hamilton County (Cincinnati) is one of the notable exceptions. There, a prosecuting attorney known for his support for the death penalty faces off against two challengers who oppose its use, and a sheriff who has drawn protests for cooperating with ICE has a contested re-election race.

—

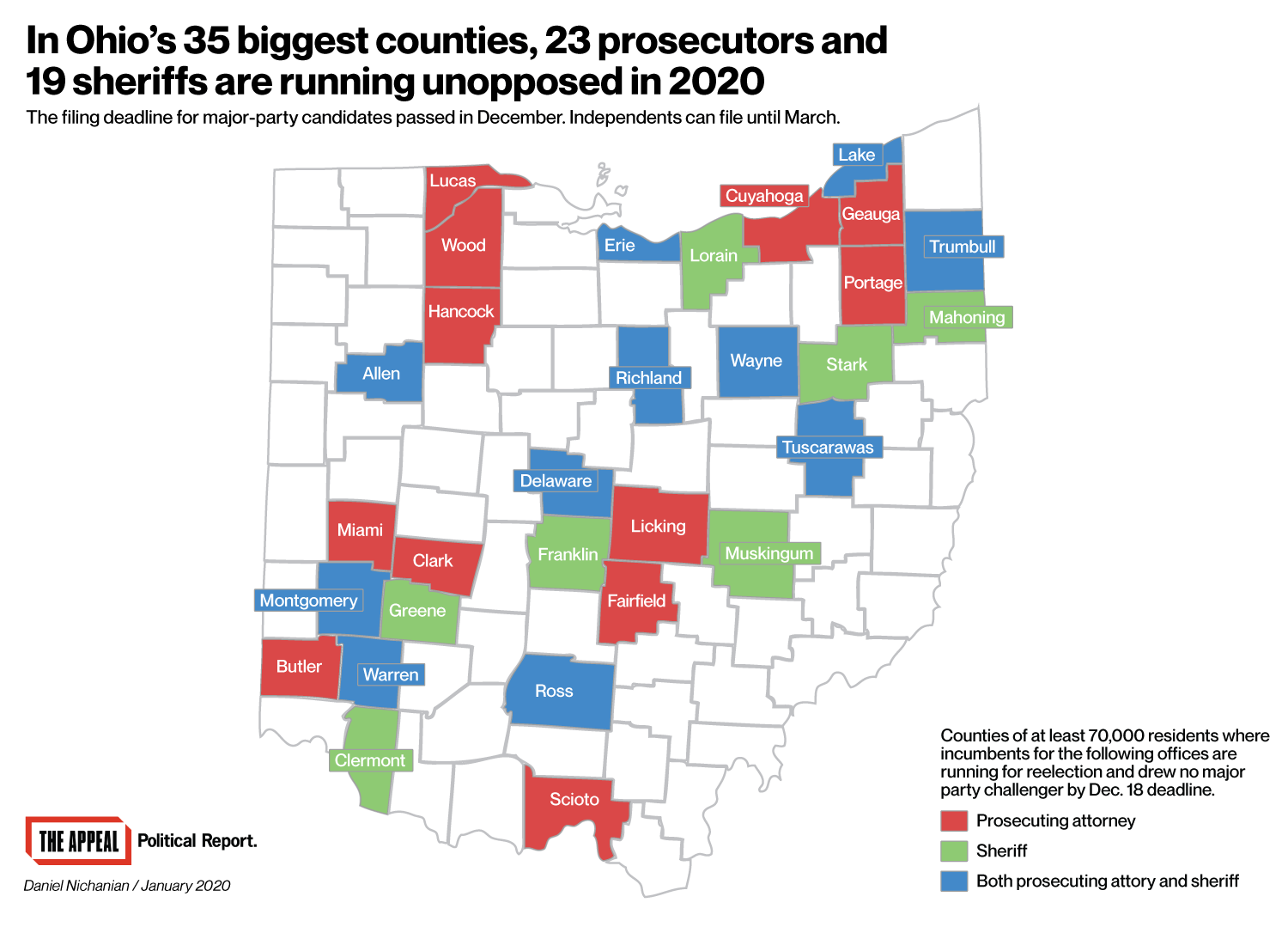

Across Ohio’s 35 biggest counties (those with at least 70,000 residents), 23 incumbent prosecutors are running for re-election with no major-party opposition, a Political Report analysis has found. This means that no one filed to challenge them by the Dec. 18 deadline for Democratic and Republican candidates; independents can still file nominating petitions until March 16.

These 23 incumbents, who are likely to secure re-election this fall, include:

- Michael O’Malley, a Democrat in Cuyahoga County (Cleveland). He has faced calls to not request cash bail amid a crisis of jail deaths. The county is also led the nation in death sentences over the past two years.

- Juergen Waldick, a Republican in Allen County, who is the incoming head of the association of state prosecutors.

- Julia Bates, a Democrat in Lucas County, David Fornshell, a Republican in Warren County, and Victor Vigluicci, a Democrat in Portage County. These prosecutors, alongside O’Malley and Waldick, fought a bipartisan bill in 2019 to end the death penalty for people with a mental illness.

- Dennis Watkins, a Democrat in Trumbull County, who recently fought a court ruling halting an execution, and who defended an assistant prosecutor who wrote social media posts mocking defendants.

- Ryan Styer, a Republican in Tuscarawas County, which has seen a large jump in felony drug possession charges (up 290 percent from 2017 to 2018), and Paul Dobson, a Republican in Wood County (Bowling Green), who defends his frequent use of drug-induced homicide charges.

- Dan Driscoll, in Clark County, and Melissa Schiffel, in Delaware County. Both Republicans, they were appointed to fill vacancies in 2019 and have not yet faced voters.

It is “hard to find candidates willing to go against the grain,” said LaTonya Goldsby, co-founder of Black Lives Matter Cleveland. Regarding Cuyahoga County, home to more than one million people, she regretted that “no one has come forward to challenge the status quo… We have to continue to organize and demand accountability from our elected officials.”

Sheriff elections are barely more competitive. Just 13 of Ohio’s 35 biggest counties with a sheriff’s race drew multiple candidates, versus 10 for prosecutors.

Butler County’s Richard Jones may be the most notable sheriff to draw no challenger. He is an advocate for arming teachers, he is the only Ohio sheriff to have contracted into ICE’s 287(g) program, which authorizes local law enforcement to act as immigration agents, and he has refused to equip his deputies with naloxone, a life-saving overdose antidote.

The Political Report has compiled a list of candidates who filed for prosecutor and sheriffs in Ohio’s 35 most populous counties.

Even in counties with a contested election for prosecutor, many candidates are running on ensuring continuity or on their prosecutorial experience, not on proposals to substantially transform the criminal legal system.

The Political Report contacted a dozen prosecutorial candidates to ask what changes, if any, they would make to their county’s prosecutorial practices and whether they saw “significantly reducing” incarceration as part of the rationale of their bids. Most either did not answer or else downplayed their interest in decarceration. Robert Gargasz, a Republican candidate running in Lorain County, rejected the notion that the incarceration rate is too high.

In Franklin County (Columbus), the state’s largest jurisdiction, longtime Republican prosecutor Ron O’Brien is seeking re-election and his sole challenger is Democrat Gary Tyack, a retired judge who has no campaign website as of publication. In answer to the Political Report’s request for comment on his policy views, Tyack replied via email that he was “not inclined” to answer, and then listed his professional experiences. He added, “I tried many cases, including death penalty cases.” The Appeal reported in December on O’Brien’s propensity to seek the death penalty.

Still, there may be important criminal justice reform conversations in some Ohio counties this year.

—

Death penalty is at issue in Cincinnati: Hamilton County prosecutor Joseph Deters, a Republican serving in a blue-leaning county, is closely associated with capital punishment. Now he faces two Democratic challengers who both say they oppose it.

Fanon Rucker, a former judge, said in November that he would not seek death sentences if elected. “I cannot see a circumstance, with all the inequities that we have in the system, that I would pursue a death penalty case,” he said.

Gabe Davis, a former federal prosecutor, told the Political Report this week that “the death penalty is simply too high a price to pay, and I do not support its use.” He said it “does not deter violent crime” and “is often used in a discriminatory and inconsistent fashion.”

Rucker and Davis both told the Political Report that they were running with an eye to advancing decarceration. “Reducing our prison and jail population is a tenet of this campaign,” Rucker said in an email through a spokesperson; he added that one tool for “decreasing mass incarceration” is “eliminating cash bail for nonviolent and low-level drug offenses.” Davis outlined a similar goal to “reduce incarceration rates in a meaningful way” by “reforming bail and expanding alternatives to incarceration for non-violent offenders.”

Rucker and Davis face off in the March 17 Democratic primary, and the winner will face Deters in November. The Political Report will return to this election in the months ahead.

—

Cincinnati has a major sheriff’s race, too: Jim Neil, the Democratic sheriff of Hamilton County who has toyed with support for President Donald Trump, has faced protests for cooperating with ICE; Neil has honored ICE detainers, which are requests by the federal agency that people suspected of being undocumented immigrants remain detained beyond their scheduled release.

In the Democratic primary in March, Neil will face challenger Charmaine McGuffey, who served as director of the county jail under Neil from 2012 to 2017; McGuffey subsequently filed a lawsuit alleging that she was facing retaliation for bringing up complaints about excessive use of force. McGuffey has said she is running to promote more rehabilitative policies in the jail. The Political Report will return to this election and what this might mean in the months ahead.

—

In Ashtabula County, a test of the impact of the opioid crisis: Colleen Mary O’Toole, a Republican and a former judge running for prosecutor in Ashtabula County (northeastern Ohio), says the opioid crisis has expanded the space for criminal justice reform.

“Everybody in Ashtabula knows someone who is strung out on drugs,” O’Toole told the Political Report. “It has changed the hearts and minds of people who historically would have said, ‘Lock them up.’ It’s taken the other, and it has put them in the house. Ten years ago I walked into a room and they were like, ‘You’re the judge, you’re going to lock them up right?’ Now they’re like, ‘How are you going to help my cousin?’”

She said she would implement changes to “shift away from incarceration” for people with drug addiction issues. She added that “21st century justice” requires other ways to reduce incarceration, including “eliminating cash bail for low-level offenses,” though she described this as a long-term goal, and not an immediate commitment. Prosecutors elsewhere have adopted policies of not seeking financial conditions for pretrial release.

Two other candidates are running in the Republican primary; the winner will face Cecilia Cooper, a Democrat who was appointed prosecutor in late 2019. Cooper did not respond to a request for comment on her own views on the opioid crisis and on whether she aims to lower incarceration.

—

Can 2020 slow the trend of drug-induced homicide prosecutions? Charging people with homicide if they provide or sell drugs that lead to an overdose fuels long sentences and often targets people with addiction issues; but the practice has surged in Ohio. In fact, few counties in the entire nation have done this as frequently as Clermont County, in the suburbs of Cincinnati, according to data collected by the Health In Justice Action Lab, a project of the Northeastern University School of Law

Clermont County is now sure to see turnover since the incumbent is not running. The only one candidate who has filed to replace him, Mark Tekulve, did not respond to a request for comment on this issue. Other counties whose prosecutors have filed such charges aggressively will host contested elections: Franklin, Hamilton, Mahoning, Medina, Summit, and Stark counties. Will any of the candidates running in these jurisdictions raise concerns about this prosecutorial trend?

—

Advocates eye other paths for change on issues such as cash bail: The majority of people held in Ohio’s jails are waiting for a trial, and advocates are demanding that the state curtail cash bail to shrink pretrial detention. While bail is set by judges, the issue is also in the hands of prosecutors, who make bail recommendations.

In counties where the current prosecutor is likely to remain in office beyond 2020, advocates can deploy pressure points other than an electoral challenge to demand change. In Cuyahoga County, various groups formed the Coalition to Stop the Inhumanity at the Cuyahoga County Jail last year to advance reform on issues such as cash bail. “We are more determined than ever to hold O’Malley’s feet to the fire,” said Goldsby, whose organization Black Lives Matter Cleveland is part of this effort. “By engaging in conversation with him about his role as prosecutor we hope to influence him to take a more progressive approach.

This coalition is “a platform that gives a voice to those that are most impacted by the criminal justice system,” Goldsby added.