Political Report

Blockbuster D.A. Races Rock Big Texas Counties, from Austin to Houston

The death penalty, drug policy, and bail reform are shaping Texas debates, with primaries just weeks away. But across the state, hundreds of local elections are left uncontested.

The death penalty, drug policy, and bail reform are shaping debates in El Paso, Harris, Nueces, Travis counties, with primaries weeks away. But across Texas, hundreds of local elections are left uncontested.

Read more coverage of the 2020 local elections.

The Texas criminal legal system is in upheaval. Confusion around a new law legalizing hemp has led to a drop in marijuana prosecutions, as some district attorneys look into extending that trend to other drugs. A court declared the bail system of the state’s largest jurisdiction (Harris County, home to Houston) to be an unconstitutional form of “wealth-based discrimination.” And the use of the death penalty has declined significantly this past decade.

Still, drug policy is very uneven across the state. Questions abound on how well Harris County will implement its new bail rules, and whether more lawsuits can force change in other counties. And Texas continues to lead the nation in the number of death sentences obtained by prosecutors.

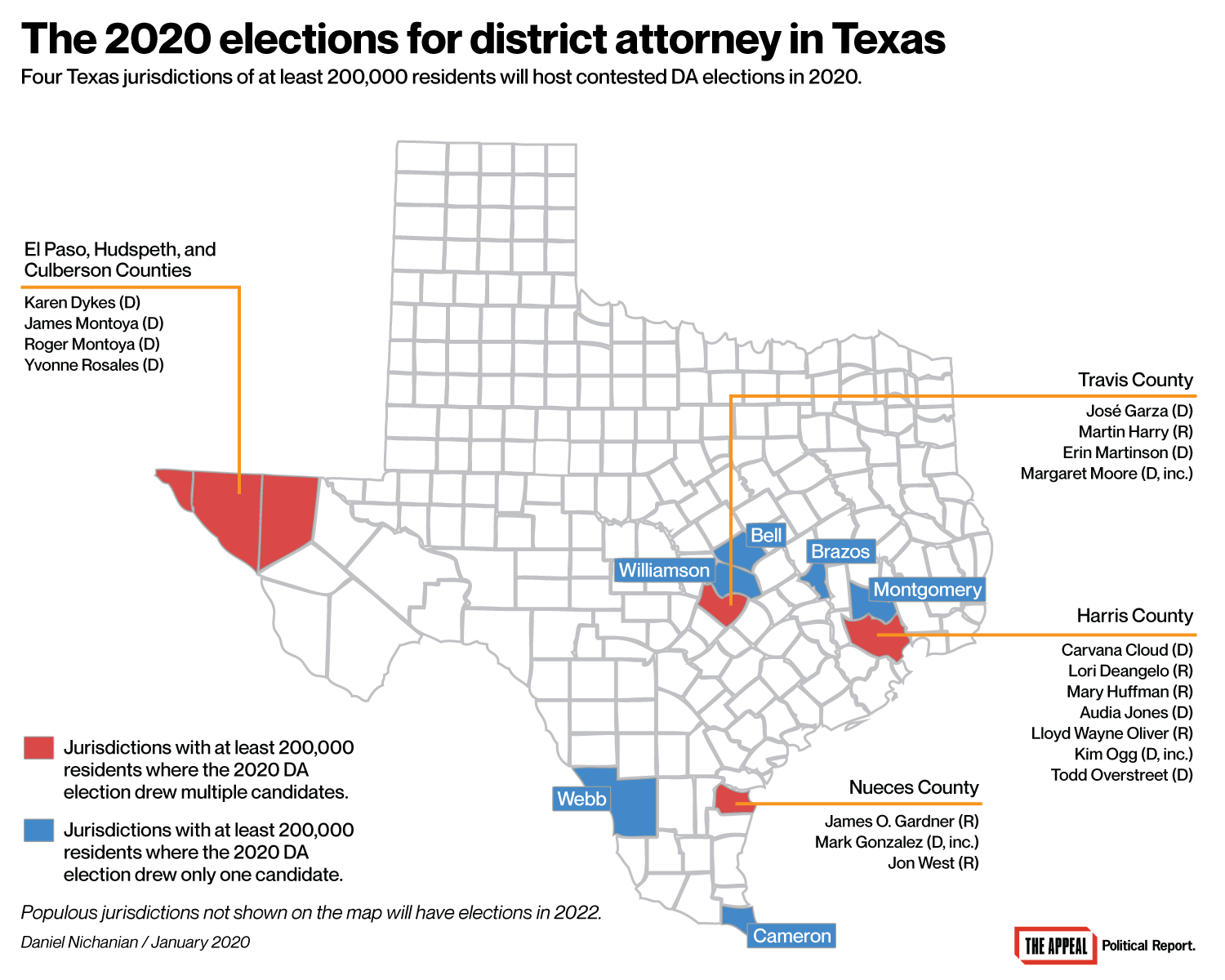

These issues are shaping blockbuster DA races this year in some of Texas’s largest counties, namely El Paso, Harris (Houston), Nueces (Corpus Christi), and Travis (Austin) counties.

In Harris and Travis, which combined have nearly 6 million residents, incumbent DAs face challenges from their left in the Democratic primaries, while in Nueces, a Democratic DA who ran on a reform platform in 2016 faces pushback from GOP opponents. In El Paso, a longtime prosecutor’s retirement has sparked a crowded open race.

These races are already marked by significant policy conflicts over the shape of prosecution. DAs, after all, enjoy significant discretion over which cases to bring, and with what severity. “When you have different prosecution philosophies, they have different results,” Jon West, a Nueces County Republican, said in an interview this month. That was in the context of faulting the incumbent for not prosecuting some low-level cases such as marijuana possession.

But other challengers say they are running instead to combat mass incarceration.

“I just could no longer sit and continue to be part of a system that targeted people of color, that targeted communities of drug addiction, that targeted low-income, the working class,” Audia Jones, who is running in Harris County, told The Appeal last year. José Garza, who is running on a decarceral platform as well in Travis County, made a similar case when he tweeted that he is “running for DA to build a system that lifts up working people and people of color.”

In most of the rest of Texas, though, incumbents are coasting to re-election with no opposition.

Seventy-six percent of the state’s 118 DA races drew only one contender by December’s filing deadline. The electoral landscape is barely more competitive in the most populous counties; of races occurring in counties with at least 100,000 residents, nearly 70 percent are uncontested.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Hundreds of other elections relevant to Texas’s legal system drew just a single candidate, including 129 county attorney races (that’s 86 percent of the total) and 109 sheriff races (43 percent). County attorneys are prosecutors who exist separately from the DA in some counties; where they do, they typically deal with misdemeanor offenses.

Primaries are set for March 3, and if no candidate crosses 50 percent the top two will move to a May runoff. General elections will be held in November. Full lists of elections and candidates are available on the Political Report’s candidate resource.

Below is a first preview of Texas’s major prosecutorial elections. You can jump to the preview of Harris County, Travis County, El Paso CountyNueces County, and the rest of the state.

—

Harris County: The county’s legal system has changed drastically since Kim Ogg won her first term as DA in 2016; a court ruling overhauled its bail rules, sparking a legal settlement under which most people charged with misdemeanors should be released pretrial. But Ogg fought that change, raising safety concerns about pretrial release, only to be rebuked by a judge.

Two of Ogg’s opponents in the Democratic primary, Jones and Carvana Cloud, told the Appeal in separate Q&As that they back this change. Jones said she supports expanding the reform to also end cash bail for felony-level offenses.

Cloud and Jones, who each used to work as prosecutors in Ogg’s office, have criticized her for seeking to expand the criminal legal system’s imprint. Ogg requested funds to hire 102 new prosecutors last year, and local activists protested that her office was already filing too many charges and that more staff would only increase this. Cloud and Jones have echoed that view in different ways. “More prosecutors means more prosecution,” Cloud told The Appeal. She has proposed pretrial diversion programs through which she would not charge people for certain offenses such as pot possession and trespass if they fulfill certain conditions.

Jones, meanwhile, has outlined a range of behaviors that she would decline to prosecute, effectively decriminalizing them. She has committed to not prosecute drug possession (beyond marijuana) as well as “offenses that target poverty.” She told the Political Report that this category covers “criminal trespass not involving dwellings,” and “low-level theft that involve crimes of necessity.” She has also said she would decline to prosecute sex work, a policy Ogg’s office said the incumbent opposes.

Of her preference to outright decline rather than divert cases, Jones told The Appeal that, “When we do things like diversion or any type of probation, we are still criminalizing those individuals.” Jones is also the only candidate in the race to say she would not seek the death penalty.

Another former prosecutor, Todd Overstreet, is also seeking the Democratic nomination. The Democratic nominee will face one of three Republicans in the general election; the county swung toward Democrats in 2018. County Attorney Vince Ryan and Sheriff Ed Gonzalez, both Democrats, face contested re-election bids as well.

—

Travis County: Margaret Moore, the incumbent DA, faces two challengers in the Democratic primary: Garza, a labor and immigrant rights attorney with the Workers Defense Project, and Erin Martinson, a former victims’ advocate at the Texas Legal Services Center. Garza was just endorsed by U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren this week.

Both challengers are running on major progressive changes.

One of Garza’s most striking promises is that, in an effort to take substance use issues out of the court system he would not prosecute the possession or the sale of under one gram of any drug. This is a distinctive proposal even by national standards of what progressive DAs have done so far; while some have rolled out blanket policies to not prosecute drug possession (even then, this is frequently focused on marijuana), it is still unusual for this approach to extend to low-level drug sales. Martinson has said she would not prosecute minor possession of drugs, beyond marijuana.

Other differences emerge in the three candidates’ answers to questionnaires published online by the Justice Collaborative. (The Appeal and the Justice Collaborative are a fiscally sponsored project of Tides Advocacy.) Garza and Martinson each endorse altogether ending the use of cash bail, unlike Moore.

Both challengers, again unlike Moore, also commit to never seek the death penalty.

But what may be most illustrative of the candidates’ differing philosophies on criminal justice is their views on the purpose of diversion programs. When is it fair and proper to encourage more rehabilitative outcomes and to avoid incarceration? Moore says people must first plead guilty and “take responsibility.” “We do not allow defendants who maintain their innocence to enter diversion,” she writes. But Garza and Martinson say they would drop this requirement that people first plead guilty as a condition of entry.

Requiring it defeats the point, Martinson says. “The purpose of diversion should be to give people a second chance and give them the tools and opportunity to break free from the criminal justice system,” she wrote. “Strapping folks with felony convictions does not set them up to succeed.”

As she runs for re-election, Moore is facing a lawsuit that alleges that she is mishandling sexual assault incidents by dismissing allegations brought by female victims.

Travis County also has an open race for county attorney, the office in charge of misdemeanors, between former judge Mike Denton, assistant prosecutor Laurie Eiserloh, Austin City Council member Delia Garza, and defense attorney Dominic Selvera, who is running on not prosecuting a range of behaviors, including misdemeanor drug possession and sex work, and on shrinking the criminal legal system. Selvera has also said he will not join Texas prosecutors’ statewide association, as has José Garza the DA candidate.

—

Nueces County: Mark Gonzalez drew national headlines for his transition from defense attorney with a tattoo that reads “Not Guilty” to DA of Nueces County in 2016. A Democrat, Gonzalez promptly announced he would stop jailing people for pot possession, and he has since supported replacing some arrests with cite-and-release policies, and participated in nationwide calls for reform, including responding to U.S. Attorney General William Barr.

The scope of Gonzalez’s reforms has come under question, though. The Appeal has reported on failures to share exculpatory material and his decision to seek the death penalty.

Still, in his re-election bid this year, Gonzalez faces attacks over his reform politics. Opponent Jon West, a Republican prosecutor, has rejected even basic premises of criminal justice reform, for instance denying that the U.S. is too harsh toward low-level nonviolent cases. “Every single case matters, even low-level drug cases,” he said in an interview. “Just because somebody may have a low-level drug arrest does not mean they might not be a violent person.” In that interview, he also insisted that the criminal legal system does not discriminate “locally”, though “it may nationally.”

In the Republican primary, West faces James Gardner, who lost to Gonzalez four years ago.

—

El Paso: All four candidates who filed to replace the retiring incumbent are Democrats, so an open Democratic primary will decide the next DA of the 34th judicial district, which includes El Paso County and smaller Culberson and Hudspeth counties. The Political Report contacted each of these candidates to ask whether they viewed reducing incarceration as a goal, and whether they favored a policy of not prosecuting certain offenses.

None of them endorsed the sort of wide-ranging measures put forth by some of the candidates in Austin and Houston, though differences emerged.

Yvonne Rosales, an attorney, mentioned initiatives to “reduce incarceration rates” for “nonviolent offenders,” such as steering people with mental-health issues toward treatment. But she qualified her answer by saying a DA must “balance” defendants’ rights and public safety; progressive DAs elsewhere have rejected the premise that those two poles are in tension. She also deemed improper a policy of not prosecuting any behavior that is illegal (including pot possession), and in any case rejected the view that “small amounts of marijuana” are “harmless.”

“I do not believe that El Paso County’s criminal justice system is excessively punitive,” said James Montoya, an assistant prosecutor, noting prison admissions are already low. (El Paso does have fewer prison admissions than other major Texas counties. But proponents of cutting incarceration tend to demand substantial reductions beyond national or state standards given that the country is a global outlier.) He added that he wants to set a pretrial diversion program for marijuana offenses.

Roger Montoya, an attorney, said he was interested in “ending mass incarceration”—the only candidate to use those terms—and specifically in ending the war on drugs; he mentioned steering people toward probation rather than incarceration over drug offenses. However, while he said he would decline to prosecute low-level of pot possession, he did not name another offense he saw fit for declination; that’s a far cry from Garza’s commitments in Austin. Montoya, who has himself been convicted of misdemeanors in the past, is campaigning on the argument that this experience helps him appreciate the importance of second chances; he told the El Paso Times it makes him “more of a humanitarian.” His opponent James Montoya went after him over his record in the Times.

Karen Dykes did not respond to a request for comment. She is a lawyer for Combined Law Enforcement Associations of Texas (CLEAT), and has support from local law enforcement groups.

—

Elsewhere: No other county of at least 200,000 residents holds a contested election this year. And only two other counties with at least 100,000 do. In Ellis and Midland counties, a GOP primary will decide the next DA.

Dozens of incumbent DAs—including in Montgomery and Williamson, both of which have more than half-a-million residents—are coasting to re-election unopposed.

And if you have not seen your county’s name in this article, you may need to wait two years: Some DAs, including those in Dallas and Bexar counties, as well as Bastrop County’s Bryan Goertz (known for rejecting DNA testing requests in the death penalty case of Rodney Reed), were last elected in 2018 and are not up for re-election until 2022.

The article has been updated to include comments made by Harris County’s DA candidates at the Jan. 30 debate.