Political Report

ICE Suffered Blows in the South in Last Week’s Elections

Voters in populous Georgia and South Carolina counties elected sheriffs who ran on ending contracts with ICE.

Voters in populous Georgia and South Carolina counties elected sheriffs who ran on ending contracts with ICE.

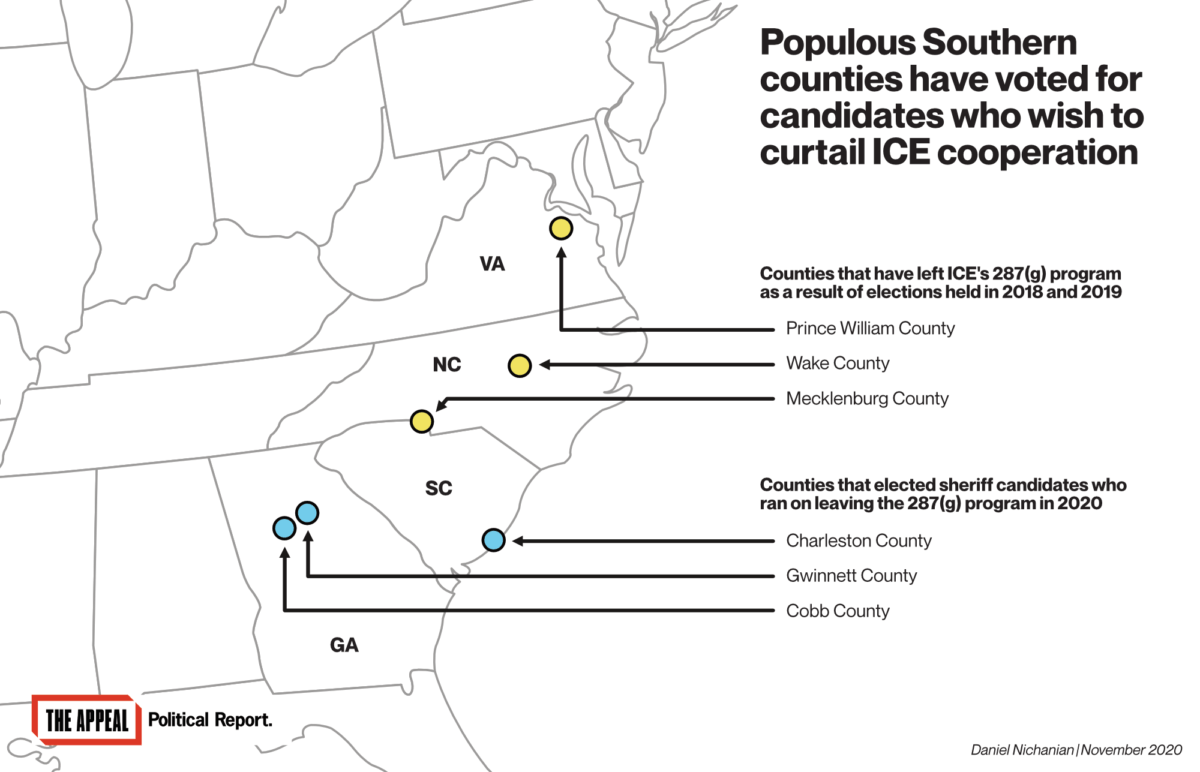

Republicans lost sheriff’s elections last week in populous Southern counties that have been close ICE allies. This is likely to bring an end to prominent ICE contracts in Georgia’s Cobb and Gwinnett counties and in Charleston County, South Carolina.

These results are major wins for immigrants’ rights advocates who have long worked to change policies in these jurisdictions, which are home to more than 2 million residents combined.

“We celebrate the ouster of the sheriffs who were responsible for the targeting of community members, working in collusion with ICE,” Azadeh Shahshahani, legal and advocacy director of Project South, told The Appeal: Political Report. “These incredible victories are the culmination of more than a decade of fighting back by immigrants’ rights organizers against the devastating 287(g) program which led to untold numbers of families being torn apart.”

Charleston, Cobb, and Gwinnett are all members of ICE’s 287(g) program, which deputizes local law enforcement to act like federal immigration agents within jails. The program has put thousands of people each year on ICE’s radar. Local officials justify this policy as a way to target people who commit violent crimes, though the vast majority of people affected were booked for lower-level offenses or were never convicted. As a result, people can be funneled into deportation proceedings and find themselves locked up in detention centers that are known for inhumane conditions. Project South is among the organizations suing ICE for failing to respond to a whistleblower complaint alleging that women in Georgia’s Irwin Detention Center were forced to undergo gynecological surgeries that could result in sterilization.

Participation in the 287(g) program is up to the sheriff—much like many other forms of cooperation with ICE—and the Democratic nominees in each of these counties ran on terminating it, a stance they reiterated in interviews with the Political Report in September and October. The Republican nominees favored the 287(g) program, by contrast. The three Democrats prevailed.

Cobb County’s longtime sheriff, Neil Warren, lost to challenger Craig Owens. In Gwinnett County, a sheriff with notoriously aggressive policies toward immigrants retired, and the resulting open race was won by Kebo Taylor.

And in Charleston County, Sheriff Al Cannon lost to Kristin Graziano, who told the Political Report in October that the 287(g) program is “contradictory to what we’re trying to accomplish in Charleston,” namely “building our communities back up and building trust.” Charleston has a separate agreement to help ICE detain people the agency arrests elsewhere, and Graziano indicated to the Political Report she opposed detaining people on noncriminal grounds.

These results add to a series of recent wins by candidates who pledged to cut ties with ICE.

In 2018, North Carolina was the epicenter of that surge, driven by extensive grassroots activism. Five of its most populous counties elected new sheriffs who ran on no longer assisting ICE, including by terminating 287(g) contracts. They promptly did so after entering office. All five of the new North Carolina sheriffs who ran on improving immigrants’ rights are Black, as are Owens and Taylor in Georgia, even as sheriffs nationally are overwhelmingly white.

Then, in 2019, Democrats took over Prince William County, Virginia’s second most populous jurisdiction, and used their newfound power to quit the 287(g) program this year.

A broader blue shift also contributed to last week’s results in Charleston, Cobb, and Gwinnett counties. Joe Biden carried each county by more than any Democratic presidential candidate since at least 1976. The two Georgia counties, in particular, are longtime conservative bastions that have seen tremendous change in their population and politics. For instance, more than two-thirds of Gwinnett County residents were white in 1996, when Butch Conway was elected sheriff and made his county a national leader in targeting immigrants. Now, it’s about a third.

Still, advocates emphasize that it took a lot of work to get these partisan flips to translate into policy commitments by candidates.

Aisha Yaqoob Mahmood, director of the Asian American Advocacy Fund, which has opposed cooperation with ICE in Georgia, told the Political Report in August that, “four years ago, nobody knew what this [287(g)] program did,” whereas this year it was a core campaign issue. “The last few years of organizing were very important for us to make sure that 287(g) becomes a top issue in this election, and it really has become that way,” she said.

Other organizations, such as Mijente, Project South, the Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights, and SONG Power, fought to curtail ICE’s reach through these sheriff’s races, and through protests and community events. And in a project sponsored by the Georgia NAACP, the group Informed Georgians for Justice sent questionnaires to all Georgia sheriff candidates, inviting them to clarify their views on immigration and other issues.

Georgia organizers had already scored a win in the June Democratic primary. Sheriff Ira Edwards lost in Athens to challenger John Williams, who took issue with the incumbent’shis record of helping ICE. Athens is not part of 287(g), but Edwards had honored ICE detainers, which are requests that he detain people beyond their scheduled release to give federal agents time to arrest them.

Williams said he would not honor ICE detainers. “It’s almost a level of terrorism when people are living in fear to the point that they will not ask for help,” he told the Political Report in June, right after his primary win. Williams also won the general election last week.

Graziano and Owens, the incoming sheriffs in Charleston and Cobb, also said during their campaigns that they would oppose ICE detainers. But Taylor, the incoming Gwinnett sheriff, left the door open to assisting ICE in ways beyond the 287(g) program. Advocates have said they will push local officials to be bolder to protect immigrants.

Graziano told the Political Report she has learned from organizers in Charleston’s Latinx community, whom she wants “sitting at the table making the decisions that affect their lives.”

Elsewhere in the country, two Republican sheriffs who have championed ICE and who joined 287(g) won in counties that narrowly went for Biden in the presidential race. Bill Waybourn in Texas’s Tarrant County (Fort Worth) and Bob Gualtieri in Florida’s Pinellas County (St. Petersburg) defeated challengers who had pledged to terminate these contracts.

But many candidates who called for winding down local relationships with ICE prevailed. Charmaine McGuffey won a heated sheriff’s race in Ohio’s Hamilton County (Cincinnati); earlier this year, she secured a primary win against a Democratic incumbent who had honored ICE detainers, which McGuffey vowed to oppose. In Massachusetts’s Norfolk County, voters ousted a GOP sheriff who had championed greater ICE cooperation.

And in Florida’s Miami-Dade County, Democrat Daniella Levine Cava flipped the mayor’s seat from the GOP. Cava ran on curtailing cooperation with ICE, which has been spearheaded by the retiring Republican incumbent Carlos Giménez, and on opposing a new state law that mandates that local law enforcement assist the federal agency.

Change will be most swift in the three 287(g) counties that elected new Democratic sheriffs. Since Election Day, the incoming Cobb and Gwinnett sheriffs have confirmed to the Atlanta Journal Constitution that they plan to exit the program. And Graziano told the Political Report in October that she would terminate the 287(g) contract “immediately” upon taking office.

She confirmed her plans through a spokesperson this week. “It will be a simple process, and I intend on keeping my promise to rescind the contract with ICE,” she said.