Political Report

COVID-19 Stalls Efforts to Help People with Felony Convictions Register to Vote

In states that restored people’s voting rights, many public agencies aren’t doing enough to assist, and the pandemic slowed grassroots plans to pick up the slack.

In six states, reforms have restored voting rights to more than one million people since 2018. But many public agencies aren’t doing enough to assist them, and the pandemic dealt a blow to grassroots plans to pick up the slack.

In December, Kentucky advocates began hosting in-person meetings and going door-to-door, informing people with felony convictions that they might now be eligible to vote due to an order by Governor Andy Beshear that restored the right to vote to about 140,000 residents.

But when COVID-19 hit, said Debbie Graner, “everything went to hell in a handbasket.”

As a member of Kentuckians for the Commonwealth (KFTC), a nonprofit group that advocates for voting rights, Graner had pushed the state to expand the right to vote for years. She was disenfranchised herself and promptly registered to vote after Beshear’s order.

But plenty of other Kentuckians with felony convictions, she said, don’t know that they are now eligible, and they may not have heard of the executive order. They will be harder to reach now that social distancing rules have stalled in-person organizing efforts.

Across the country, the pandemic has posed serious challenges to the campaigns that voting rights groups had planned to reach new voters and help them register. Registration drives usually consist of in-person events and public interactions. Advocates are now doing their best to reach people largely through phone calls, texts, and social media, though these methods pale next to the task at hand when it comes to assisting those whose rights have recently been restored.

Since the 2018 midterms, the last national election, six states—Colorado, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Nevada, and New Jersey—have expanded the right to vote and restricted the disenfranchisement of people with felony convictions. They did so to varying degrees: some enfranchised people who have completed their sentence, while others enfranchised people who are on parole or on probation. Collectively, they restored the voting rights of more than 1.8 million people.

But the sort of outreach that is now sidelined is crucial to ensuring that these newly enfranchised individuals register to vote, advocates stressed, often emphasizing that the state has not done nearly enough to help. People who have interacted with the criminal legal system are less likely than others to register. In some of these states—especially Kentucky, Louisiana, and Florida—this is compounded by the additional hurdles that the newly enfranchised must overcome in order to register. These include figuring out if they are even eligible to vote amid insufficient state information and taking extra steps to register. Now more than ever, these government-imposed burdens are threatening to keep people from exercising their right to vote in a key election year.

—

Colorado, Nevada, and New Jersey each adopted a simple rule in 2019: “If you’re not incarcerated, you can vote,” as Henal Patel, director of the Democracy and Justice program at the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice put it. Their new laws enfranchised people who are on parole and on probation, along with anyone who is done with a sentence. As a result, there are now 18 states where anyone who is not in prison can vote; that includes Maine and Vermont, which enable incarcerated people to vote as well.

This makes eligibility a straightforward matter. Having such a “clean law,” Patel stressed, makes a huge difference for voter registration.

These three states also take on active roles in registering people to vote. Each has a system to automatically register eligible people when they come in contact with particular state agencies, usually a Department of Motor Vehicles.

That said, none of these states’ new laws mandated that agencies automatically register those whom they newly enfranchised, nor that they give them registration forms when they come in contact with parole or probation officials.

Advocates with the NJISJ and the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition said state officials are working with them to set up mechanisms to inform newly enfranchised people, for instance by distributing informational material upon contact with parole and probation offices.

They have also launched efforts to maximize the impact of the new rules and to inform people that they may have newly gained the right to vote. The NJISJ had planned events on March 17 in three cities, hoping to draw hundreds or even thousands of people to register.

But then the pandemic hit and the events were canceled.

Instead, Ronald Pierce, a fellow at NJISJ who has been on parole and who regained the franchise for the first time since 1985, and Antonne Henshaw, another state advocate, signed registration forms during a live streamed event in Newark. “I am now back as a part of the community,” Pierce later told the Political Report.

—

In Florida, Kentucky, and Louisiana, by contrast, residents with felony convictions still face much more complicated rules to figure out their eligibility. Even with the new reforms, these states are continuing to disenfranchise hundreds of thousands of people who are not incarcerated—many of whom have completed their sentence—relying on often-complex legal distinctions as to who can vote and who cannot.

These distinctions—including type of conviction, length of time since incarceration, financial obligations, and other factors—make it far more difficult for prospective voters to know if they are eligible and for nonprofit groups to help them register.

Public authorities, for the most part, are not helping inform or register their newly enfranchised residents.

Advocates across several states told the Political Report that this situation has a chilling effect. People don’t want to risk voting when ineligible—even if unintentionally—and being punished for it.

In Kentucky, for instance, Beshear’s order enfranchised people who have completed sentences for a felony defined as nonviolent. But as in many states, it’s not always clear to the public, including those with convictions, what counts as “violent.” The state is doing little to help sort out this confusion and actively inform people that they are eligible, Graner and others at KFTC said, beyond setting up a website where people can enter their name to check if they are now able to vote.

Blair Bowie, who leads the nonprofit Campaign Legal Center’s Restore Your Vote campaign across several states, including Kentucky, said, “there’s a lot that the state can and should be doing [in Kentucky and elsewhere] to help overcome the persistent notion that you can never vote again after a felony—which is really seared into the public zeitgeist.” Kentucky’s tool for people to figure out if they are eligible to vote compares favorably with those of states like Alabama and Tennessee, which have made it difficult for people to even get such information, Bowie added, but Kentucky could be reaching out more proactively. She said the Restore Your Vote campaign is now placing targeted ads on social media and partnering with local advocacy groups to use texting to individually help people register.

Louisiana has entertained uncertainty as well, according to organizers with the Louisiana-based nonprofit Voters Organized to Educate as well as its sister organization, the criminal justice advocacy group Voice of the Experienced.

The state’s new law allows people on parole and probation to vote if they haven’t been incarcerated for at least five years. (All Louisianans with a completed sentence could already vote.) In the run-up to its implementation in 2019, the law proved to be confusing to the very politicians who passed it: Some had not realized that many people on probation were never incarcerated and had their rights restored with no waiting period.

Last year, Louisiana’s secretary of state said that he expected third party groups, rather than the government, to spread the word about these new rules.

“How are they going to put that on formerly incarcerated people and on advocates to make sure that all 35,000 people know that they have the right to vote?” asked Checo Yancy, policy director of Voters Organized to Educate, referring to the number of people directly enfranchised by the law. “We don’t have the resources to do that.”

Asked for comment on its outreach plans, the secretary of state’s office pointed to a statute requiring that correctional officials inform people of the procedures to regain their rights and give them a voter registration form upon their release from prison. Many people have to wait for years after their release, though, and this mandate would not inform those who were already on probation and parole when the law passed.

Last year, Voice of the Experienced began going to parole and probation offices to find newly enfranchised people and inform them of their newfound eligibility. But the pandemic shut down those offices, which has made it more difficult for the organization to reach people and help them register.

Most of the organization’s outreach is now virtual, said Bruce Reilly, its deputy director, and there are challenges to reaching people with limited access to the internet.

Florida advocates have faced similar obstacles, and The Appeal reported in March that state residents have been afraid of registering to vote. The Florida Department of State “sat on its hands for a year” instead of helping inform people, said Jonathan Topaz, a fellow at the ACLU’s Voting Rights project, and “we know as a matter of fact that many people have been chilled from voting in elections that they may well have been eligible to vote in.” The secretaries of state offices in Florida and Kentucky did not answer requests for comment.

—

Beyond insufficient state outreach, prospective voters in Florida and Louisiana must overcome state-imposed administrative and financial burdens, which is harder now due to the pandemic.

In Louisiana, newly enfranchised residents who wish to register to vote must obtain a form from the office of probation or parole attesting that they are eligible, and then bring it to their parish registrar’s office in person, unless they are “disabled and homebound.”

This was already a prohibitive burden. But during COVID-19, these steps have become even more difficult and hazardous for the health of would-be voters. The registrar’s office in Orleans Parish told the Political Report on the phone this week that, even now, during the pandemic, it was requiring residents to bring the form in person and was not offering expanded mail, email, or fax alternatives.

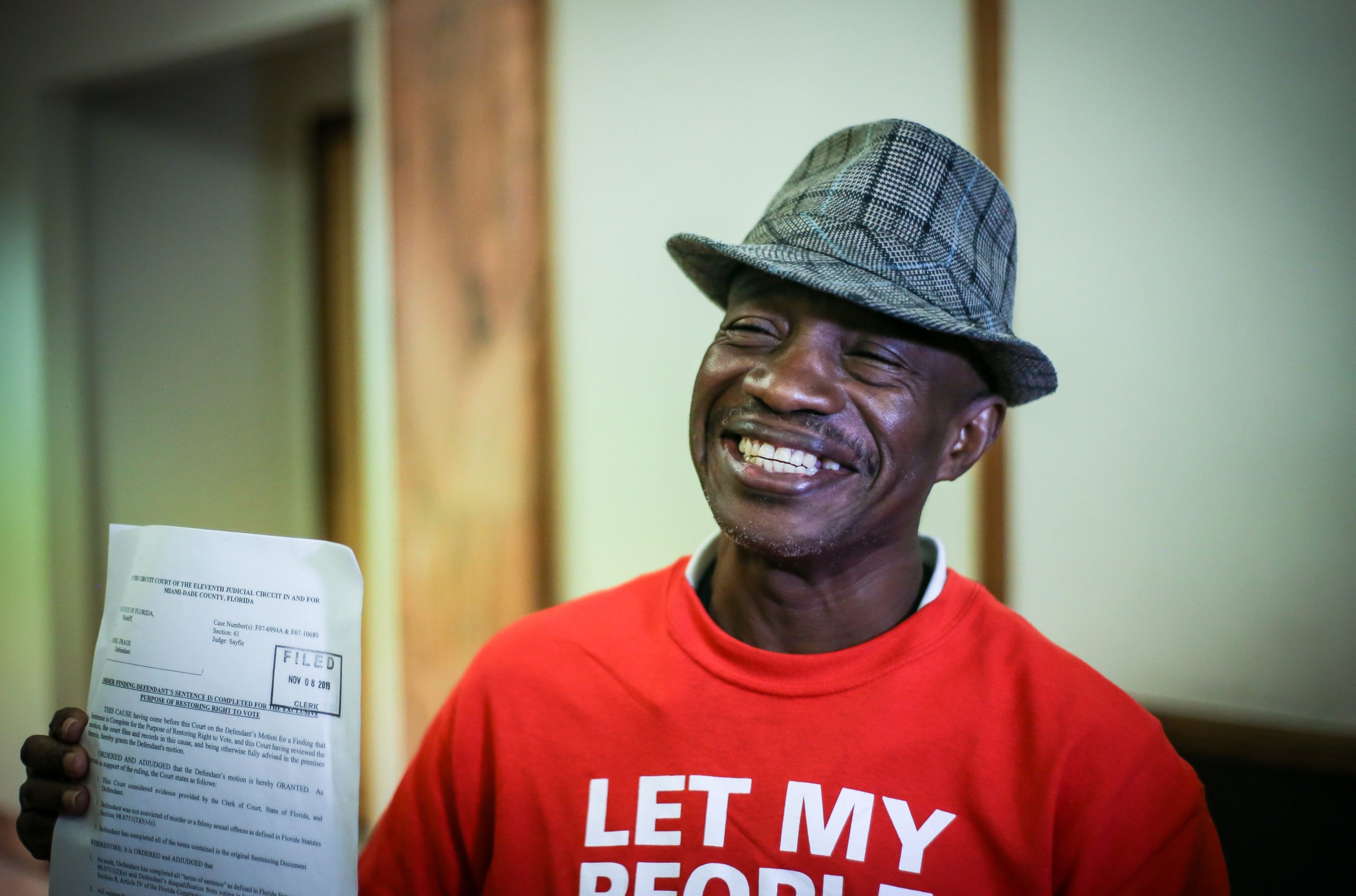

The biggest threat to the promise of expanded enfranchisement this year may be the burden that Florida put into place in 2019. In 2018, state voters overwhelmingly adopted Amendment 4, a ballot initiative championed by the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition (FRRC) and other groups that restored the voting rights of Floridians who complete their sentence for most felony convictions. But the following year, the state’s Republican legislature adopted a new law that required people to pay off the financial obligations related to their conviction before they could register. Civil rights groups sued, arguing that the law amounted to an unconstitutional “poll tax” because it tied the franchise to one’s wealth.

They won a major victory on Sunday. A federal judge, Robert Hinkle, struck down the requirement that people pay off court fees before registering to vote, and ruled that people who owe fines can still register if they genuinely cannot afford payment. The ruling once again restores voting rights to hundreds of thousands, though the governor has said he will appeal.

Hinkle stressed in his ruling that Florida did not even have a system to tell people whether they owed financial obligations.

Andrew Warren, state attorney of Hillsborough County, warned that Hinkle’s ruling is complex enough that outreach is as essential as ever. It “crystallized some of the constitutional issues,” he said, but “anytime you have legal battles about what peoples’ rights are, it requires some healthy communication and education for people to understand.”

Third-party groups such as the FRRC are helping people work through this informational minefield, but the pandemic has slowed contact.

It has also slowed down separate efforts by Democratic-leaning counties, including Hillsborough County, to ensure that people with financial obligations can register. Warren’s office, for instance, partnered with other county officials and the FRRC to set up a new process in which people go before a judge to show their inability to pay fines and fees in so-called “rocket dockets” that could waive some of these financial obligations.

Warren told the Political Report they had planned to begin the court process in early March, but that COVID-19 delayed it for months. The first hearing, with 19 people, is now planned for next week.

The pandemic “just slowed down everything,” Warren said, particularly since many of the people who will benefit did not have online video conferencing access. (The first hearing will be in person.) He added that his office will stay the course it had planned prior to Hinkle’s ruling. “We want to protect against the possibility that the system that the judge set up is struck down or changed or challenged in any way,” he said.

—

Part of the challenge of registering people during the pandemic is that job losses, housing insecurity, and illness are taking a huge toll on people. “People are trying to stay alive right now,” Yancy said. “Voting is probably in the back of their mind.“

In Florida, the FRRC was collecting money to pay off people’s court debt. It had raised enough funds to register about 1,000 people, Desmond Meade, executive director of the FRRC, told the Political Report, and is continuing to pay off their debts. It is now also focused on donating thousands of protective face masks to local jails, among other places.

Incarcerated people throughout the country are often denied basic protective gear, and they are getting sick and dying at exceptionally high rates.

New Jersey has the highest rate of death from COVID-19 among incarcerated people, at 42 people as of mid-May.

Pierce of the NJISJ said this has made him more committed than ever to push for change. He argues that the dire conditions in state prisons is, in part, a consequence of denying incarcerated people the right to vote.

The NJISJ has pushed New Jersey to be bolder than its 2019 law and join Maine and Vermont in also enfranchising incarcerated people. “I don’t believe that the most fundamental right, the right to protect all other rights, should be denied to people just because they’re incarcerated,” Pierce said.

Meade also thinks that public officials’ failure to protect their constituents makes accountability more important than ever. “I believe that COVID-19 has presented a great opportunity to really highlight the importance of voting, especially with newly registered returning citizens,” he said. “And we encourage them to really pay close attention to how elected officials are responding to this COVID-19 crisis.”