Political Report

“It Is Not Smart to Focus on Prosecuting Victimless Crimes like Drug Possession:” A Q&A with Amy Ashworth

Amy Ashworth, who is running for prosecutor of Prince William County, discusses declinations, the death penalty, and cash bail.

Amy Ashworth, who is running for commonwealth’s attorney of Prince William County, discusses declinations, the death penalty, and cash bail.

You can visit the Political Report’s coverage of the 2019 elections here.

The position of commonwealth’s attorney in Prince William, a populous county in Northern Virginia, is up for grabs for the first time in decades. Paul Ebert, a Democrat whose office is known for frequently pursuing the death penalty and for findings of misconduct, is retiring after 51 years in office. Last week, I talked to Tracey Lenox, a criminal defense attorney and one of the two candidates running to replace Ebert in the June 11 Democratic primary.

This week, I talked to Amy Ashworth, a private attorney and a former prosecutor in the commonwealth’s attorney office. She is also running in the June 11 Democratic primary. (The primary winner will then face Mike May, a former county supervisor who has already secured the GOP nomination, in November.)

Ashworth told me that she supported decriminalizing or legalizing marijuana, and repealing the death penalty. She said that until those changes become law, however, she would remain open to seeking the death penalty, and she would not institute a policy of declining to pursue certain types of charges like marijuana possession (as prosecutors have done elsewhere). She argued that such blanket declinations would violate her oath of office. She explained that she would instead use diversion programs and alternatives to incarceration for “the vast majority” of marijuana possession cases and for “many first offender nonviolent misdemeanors.” She added that she would focus elsewhere than on these cases, but emphasized as well that there should still be penalties associated with them because “that is the point of the criminal justice system.” Ashworth also discussed why cash bail has “unfairly punished” defendants, and she reiterated her opposition to Prince William County’s 287(g) contract with ICE.

The interview has been condensed and lightly edited.

Your campaign website states that you are “personally against” the death penalty. How would translate to your actions in office? If elected, would you ever seek the death penalty, and if so under what circumstances would you consider doing so?

As commonwealth’s attorney, I would take an oath to uphold the laws of Virginia, and the death penalty is legal in Virginia. I do not think the death penalty is appropriate in most cases, and it’s difficult for me to offer hypotheticals about when I would consider pursuing the death penalty. The crime would have to be so egregious that life in prison without parole would not do justice to the victims and their families. The bottom line is the death penalty should be extraordinarily rare. Under our current commonwealth’s attorney, Paul Ebert, Prince William County was ranked second in the nation for sending inmates to death row. When I’m elected, this trend will stop.

What are examples of the sort of circumstance in which Paul Ebert has sought the death penalty, but where you think this sentence would be excessive?

I am not comfortable going back and second-guessing the decisions that the prosecutor has made. As I said, I am personally opposed to the death penalty. I would support legislation to remove it from Virginia’s law. However, given that it is part of Virginia’s law and I would swear to uphold that law, I can only say that it would have to be an extremely egregious case. The shooting of the kindergartners comes to mind, anybody that would target that would commit a group and commit mass homicide come to mind as that type of cases. Certainly cases where the identity of the perpetrator is well-known.

Some prosecutors have rolled out policies to decline to prosecute certain cases like marijuana possession, or expand diversion programs that don’t rely on filing charges or obtaining a conviction. Are there offenses that you would altogether decline to prosecute, or for which you would expand opportunities for pre-charge diversion? In particular, would you continue prosecuting cases of marijuana possession, and would you seek jail time for drug possession?

It is not smart to focus on prosecuting victimless crimes like drug possession or driving on suspended. I would welcome a change in our laws that decriminalizes or legalizes marijuana with restrictions on sales similar to those on alcohol. As commonwealth’s attorney, I would take an oath to uphold the laws of Virginia, which means enforcing the laws as they are currently written. However, in the vast majority of possession of marijuana cases, we would not seek conviction or incarceration and would look to divert cases from the criminal justice system. The Commonwealth’s Attorney’s Office has limited resources and should be focused on crimes that case the most harm. Other crimes for which we can and should consider diversion include many first offender nonviolent misdemeanors.

What is the scope of these misdemeanor offenses for which you’d consider diversion programs?

I am open to diversion in cases where we’re talking about first offenders, young adults, nonviolent offenses, situations where a victim can be made whole, where a perpetrator is remorseful for his actions. Those are the type of cases that I would be open to diversion from conviction. There would have to be a penalty associated with it, that is the point of the criminal justice system, but I don’t necessarily think it has to be incarceration. It could be fines, it could be community services. There are a lot of alternatives to just incarcerating somebody.

Returning to your point about enforcement: Some prosecutors have announced they won’t be prosecuting some charges, for instance Baltimore’s prosecuting attorney has said that she will not file marijuana possession charges. Could you explain further why you would not pursue such a policy and altogether decline to prosecute certain charges?

I think when you take an oath to uphold the law, you can’t just say I’m not going to prosecute certain crimes, unless you have a good faith reason to believe that that law is unconstitutional as written. If it’s a valid law, you can use your discretion in how you handle each individual charge, but you can’t blanketly say I won’t uphold my oath, which is basically what you’re saying. There are certainly older laws that are arguably unconstitutional. In those cases, if you have a reason to suspect that the law itself is not valid, that’s a different scenario than just saying I’m not going to prosecute this crime because I don’t like it. That’s not your job as prosecutor. That’s contrary to your oath.

I’d like to further probe this question of the scope and limits of using discretion. On your website, you praise the policy that former Governor McAuliffe instituted of issuing executive orders to restore the voting rights of all individuals who complete their sentence. When it comes to how officials use discretion, what do you think is the difference between that policy, and a declination policy? Is that a relevant comparison?

Not really. The governor has the discretion to restore voting rights. What the Supreme Court ended up saying is that the way he did it was incorrect, that he had to do it individually. That’s entirely different from a prosecutor’s discretion, and I think it violates your oath to office to say that you are going to disregard particular types of charges. You can in an individual case as a prosecutor use your discretion to treat that individual fairly based upon the facts and circumstances of that individual case.

So perhaps it’s not an unfair comparison because when the governor restored the rights individually, in each individual case, that was acceptable. That was in compliance with the law. Maybe I’m not saying it’s different.

If it’s a matter of having the opportunity to review the cases individually, would you be open to having a bias toward declination toward some categories of cases?

Yes, and I said that. I said I want to focus our resources in the commonwealth’s attorney’s office on the crimes that cause the most harm, so your violent crimes, your special victims crimes, those sort of things. I’m not saying I wouldn’t prosecute other crimes, obviously I would I have a duty to do that. But do you have to incarcerate first-time offenders on nonviolent cases? Probably not.

The state’s incarceration rate is higher than the national average. Do you believe prosecutors play a role in impacting mass incarceration? Would a significant reduction in incarceration be a goal you would pursue as commonwealth’s attorney, and what specific reforms would you pursue to reach such a goal?

Prosecutors absolutely play a role in mass incarceration. As commonwealth’s attorney, I will stop the use of cash bail to reduce our jail population. Additionally, prosecutors have a number of dispositional alternatives to incarceration for those awaiting trial on nonviolent offenses, such as payment of fines, community service, therapy, and treatment or rehabilitation programs. For nonviolent first offenses, especially for juvenile offenders, it is often appropriate to utilize these dispositional alternatives that keep people out of prison, thereby reducing our prison population. We must also consider the role of mental illness and help those with mental health diagnoses seek treatment rather than incarcerate them.

You mentioned wanting to stop using cash bail. Why do you think cash bail is a problem, and what is the scope of this commitment? Are there circumstances where you think its use of cash bail is appropriate?

In the vast majority of cases, while somebody is awaiting trial and they’re presumed to be innocent, if they’re not at risk of fleeing and being a danger to society, then it doesn’t have to a cash bond. They can be released on their own recognizance, they can be released on conditions such as reporting to a pretrial supervisor. Again, we’re talking about people who are not at risk to society, or to themselves, and not at risk to leave the jurisdiction.

The cash bond system has often unfairly punished people who cannot afford to make those bonds, and disproportionately affected people of color. When you are held in jail, there is a good chance that you’re going to lose your job, your housing. Ultimately, you may not be convicted of a crime yet you’ve paid a tremendous price because you couldn’t afford a cash bond. That’s the problem with the cash bond system when we apply it to every single case.

Do you think there are steps that the office should take to change the way crimes involving violence are handled, for instance in charging and sentencing practices or with restorative justice?

Your crime of violence, your large scale narcotic traffickers, your gangs, all of those need to be prosecuted to keep our community safe. Those are cases that are probably not be eligible for bonds at all because they’re crimes of violence or they involve flight reform. When we’re talking about bail reform, we’re not necessarily talking about those types of cases.

We have in Virginia sentencing guidelines. An individual receives a certain score based on their sentence and some of the factors that are involved in the crime, like if a weapon is used your score is higher. Your score gives you a range of sentences for the judge to consider. They are not mandatory, the judge can go below those guidelines or above them. But those guidelines set a general range for people charged with this crime, with those particular background and factors. Using your guidelines, you can try to ensure that sentences are consistent across the board, so there’s no point for being a particular religion, or a race, or whether you’re male or female or anything else. It’s meant to give some consistency across the entire state, and I think using those guidelines are a good step in reducing any disparity in sentencing. Another good step would be diversifying the prosecutors that work within the office to reflect more of the community so you have different backgrounds, different cultures within the office, and use implicit bias training so that people are aware that racial discrimination exists in our criminal justice system, and we have to proactively make sure that we are doing what we can to stop it.

Do you think the current guidelines are generally fair? Are there circumstances where you would you look to go below the guidelines?

I think you have to look at each case individually, always. There are different circumstances why a prosecutor would make a recommendation that’s below the guidelines and sometimes above the guidelines. There are a lot of factors that come into play in each individual case.

Your website states that Prince William County’s 287(g) contract with ICE (one of only two in the state of Virginia) which is “created an entire class of people that were too afraid to call upon the police.” Do you think that the county should quit this program, and would you speak in favor of withdrawal if elected? Are there steps that you would take as prosecutor to ease the fear that you describe, or shield noncitizens from immigration consequences of prosecution?

I absolutely believe the county should quit the 287(g) program and I would speak out against the 287(g) program if elected. As commonwealth’s attorney, I would work to diversify the office so it better reflects the people of our jurisdiction. I would be an active participant in the community and engage community leaders. I would handle undocumented immigrants the same as everyone else: fairly and equally under the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Sometimes the same charge can bring collateral consequences for a noncitizen, but does not have those consequences for someone who is a citizen. Would that feature in how you make charging and sentencing recommendation?

Absolutely. It has to. You are absolutely right, sometimes because of somebody’s status there are collateral consequences to a conviction. The collateral consequences will be a far harsher punishment than what was ever intended or is appropriate. That’s when you use your prosecutorial discretion and fashion a remedy so that you can exact justice and you can make sure that the person is made whole and understands what is happening and why. You have to take these things in consideration.

You announced a run for prosecutor before Commonwealth’s Attorney Paul Ebert announced his retirement. What led you to decide to challenge him, and were there aspects of his record that you were concerned about?

Having worked in the office for eleven years, I know and am familiar with the good things about the office, and the things that need to change. And when I heard that Mr. Ebert was going to run for another term, I decided to challenge him because there are things in the office that need to be addressed as evidenced by the recent ethical violation of one of the prosecutors in the office at the direction apparently of the chief deputy that resulted in a Virginia State Bar public reprimand. The fact that they missed deadlines in a capital murder case twice was another reason. After I left the office, people would come to me and tell me about stories that were happening in the office that they weren’t happy about. All of these things combined.

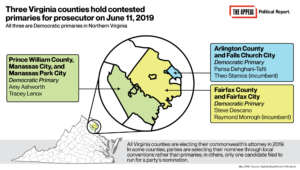

This election is one of three contested prosecutorial primaries races happening in Virginia this year.

The Appeal: Political Report has also interviewed Parisa Dehghni-Tafti (Arlington County), Steve Descano (Fairfax County), and Tracey Lenox (Prince William County).