Political Report

Oregon Could Become the First State to Decriminalize Drugs in November

A ballot initiative could decriminalize low-level drug possession and fund addiction treatment.

A ballot initiative could decriminalize low-level drug possession and fund addiction treatment.

Getting caught with drugs like cocaine, heroin, or methamphetamine normally leads to arrest, jail time, and a criminal record. But that could change in Oregon, which in November could become the first state in the nation to decriminalize possession of personal amounts of drugs, weighing between a gram or two depending on the substance.

Known as Measure 110, or the Drug Addiction Treatment and Recovery Act, the citizen-led ballot initiative would swap arrests and criminal penalties for a noncriminal $100 citation, and it would fund more treatment services. This would mark a momentous shift in favor of a public health-focused approach to substance use, and a turn away from policies that incarcerate people or at least saddle them with a criminal conviction over behaviors tied to addiction.

“What we’re really trying to do is move substance use out of a criminal justice model and into a healthcare model where it belongs,” said Haven Wheelock, one of the initiative’s chief petitioners. Wheelock also works at downtown Portland’s Outside In, providing services to homeless youth and people who use drugs. “Punishing people for a substance use disorder is an ineffective way of changing people’s drug use behavior. We know that because we’ve been trying for a hundred years to punish people into not using substances, and it hasn’t worked.”

People who are booked in jail for substance use face heightened health risks given the substantial rate of overdoses and suicides in detention or upon release. And a criminal conviction over substance use often leads to mounting economic difficulties by limiting access to housing, employment, and student loans, which can make recovery more difficult.

Measure 110 would wipe away the vast majority of criminal cases for drug possession, a state analysis found. It would not decriminalize offenses associated with drug sales, nor would it stop law enforcement against drug possession since this would be treated as a civil infraction.

Compared to other states, Oregon has a high rate of addiction while also ranking last in treatment accessibility, according to government surveys. To address these trends, Measure 110 has provisions that would use excess cannabis tax revenue, as well as savings from reduced policing and incarceration, to fund treatment and other health services.

The $100 fine would be waived if a person agrees to a health assessment where they would be screened for a substance use disorder and other health needs by licensed professionals.

This initiative is modeled after reforms undertaken by Portugal. In the 1990s, Portugal faced an injection drug crisis that led to a growing number of overdoses and an outbreak of HIV. To tackle the issue, drugs were decriminalized; in addition, new policies focused on boosting treatment and prevention programs.

“You can’t do one without the other,” Matt Sutton, a spokesperson for the New York-based nonprofit Drug Policy Alliance, told The Appeal: Political Report. The organization’s political arm has put more than $2.5 million into the Measure 110 campaign.

Since Portugal changed its approach, drug-related deaths, drug use, and HIV infections have all plummeted.

This matches a growing body of evidence in the U.S. that shows that tougher prison sentences do little to deter drug use, and that higher rates of drug arrests do not correlate with use patterns. Still, some law enforcement officials oppose the measure on the grounds that it will threaten public safety. “This is a terrible idea,” Washington County District Attorney Kevin Barton told a local Fox affiliate. “It will lead to increased crime and increased drug use.”

The measure has broad support among trade unions, faith groups, human rights organizations, as well as some law enforcement officials like Multnomah County District Attorney Michael Schmidt.

Drug decriminalization is different from drug legalization. Wheelock likened decriminalization to a speeding ticket. “It’s still not legal, you’re not supposed to get caught with these things,” she said. “You’re also not supposed to speed, and people shouldn’t go to jail for speeding, that’s why they get a ticket.”

But this continued role for law enforcement has some advocates worried that inequalities tied to policing will persist even if Measure 110 passes.

—

The decriminalization initiative lands in Oregon during a volatile political moment. Since the May 25 police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Portland protesters have risen up against police brutality and are demanding cuts to police budgets. When the campaign behind Measure 110 launched in February, Wheelock and her colleagues thought the political message with the broadest support would be one that emphasized expanding treatment.

More recently, the campaign’s message has focused on racial justice, highlighting disparities in drug arrests and the harms of the drug war on communities of color, like over-policing and over-incarceration. “In light of these protests, people universally understand and are calling for decriminalization,” Wheelock said. “That’s definitely changed not just how the campaign talks about it, but what messaging people are feeling the strongest about.”

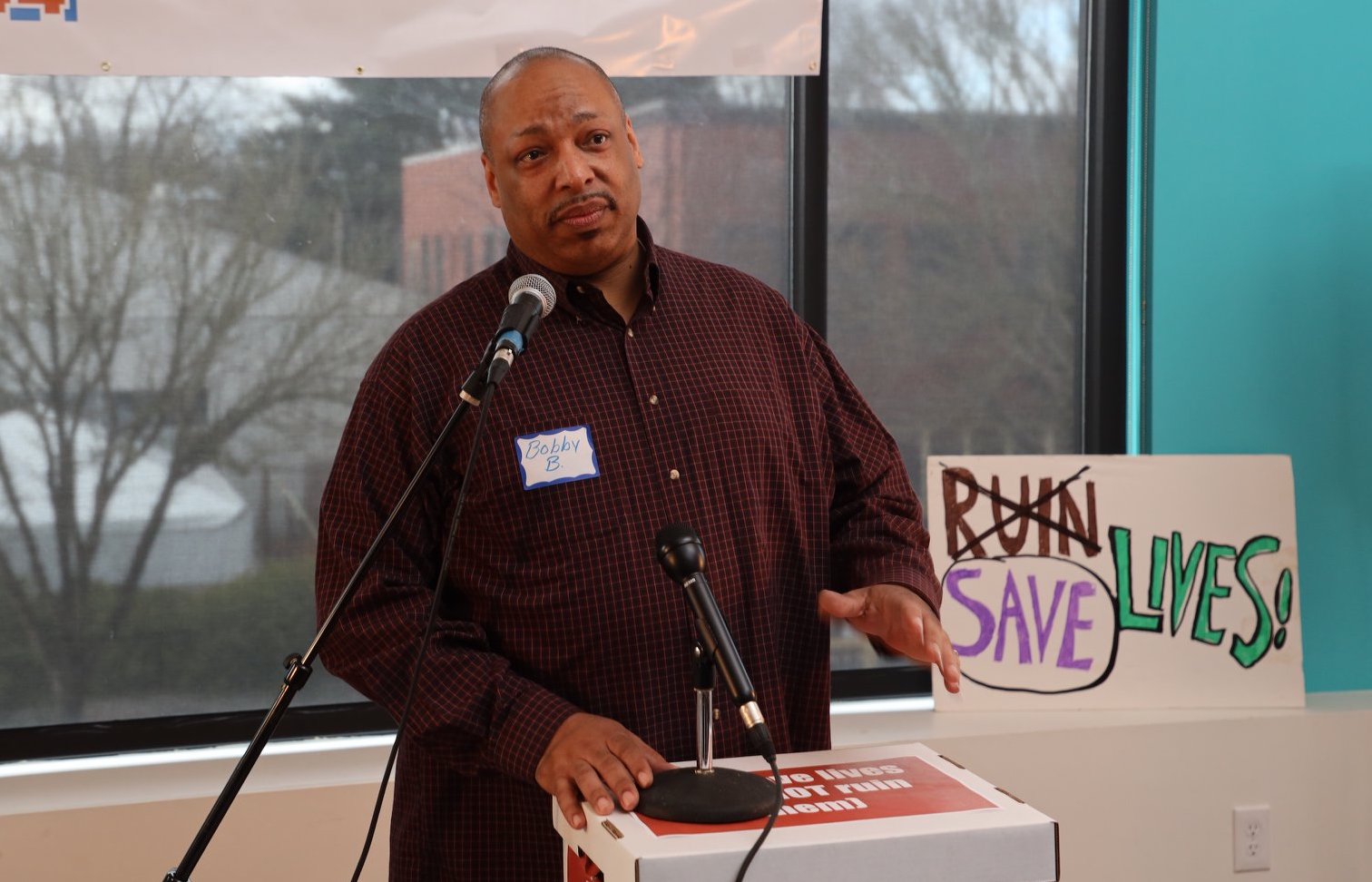

A new campaign commercial reflects the political sea change. “Two and a half decades ago, I was arrested for a small possession of drugs,” Bobby Byrd, a Black Oregon resident, said in the Measure 110 ad. “It’s kept me from getting housing, apartments, getting places near my kids, now I have to travel three hours to go see them. … It makes me feel like I’m trapped.”

At the request of the Measure 110 campaign, the Oregon Criminal Justice Commission conducted a racial and ethnic impact report analyzing the potential effects of the ballot initiative. The commission found the initiative would reduce simple possession convictions by 91 percent, and convictions of Black people by over 93 percent.

Despite the promises of reduced racial disparities and more funding for treatment, some politicians and players in Oregon’s addiction treatment industry have voiced criticism of Measure 110’s funding strategy. Though some still favor decriminalization, they are worried that Measure 110 could stymie efforts to raise alcohol taxes that would generate new revenue for substance use treatment. Rather than creating new revenue, Measure 110 would earmark existing funds from cannabis taxes. The ballot’s critics argue that means less money for other projects.

This conflict led one of the measure’s backers, the Urban League of Portland, to “pause” its endorsement.

“Unfortunately, alcohol taxes are a really big lift, and really hard to get passed,” Wheelock said in response to the ballot’s critics. “We are in a crisis where people are dying on the regular from their substance use disorders and this is something we can do right now.” She added, “In the long term, of course I’m going to fight for an alcohol tax to fund recovery services. This isn’t the end all be all.”

Measure 110 was written with flexibility in mind, leaving open the possibility to fine tune how resources are spent in the future and adapt to the state’s evolving needs. If the measure passes, those who are criticizing it now could have a say in how spending is structured down the road.

Others worry that the initiative will not be sufficient to stop the disparate harm of law enforcement. They note that the $100 citation could simply create a new form of fines and fees that target people of color and burden those with lower incomes. A 2017 report by the Drug Policy Alliance notes that “de jure decriminalization is often not enough—changes in law enforcement practices are needed as well.”

A report by the ACLU also shows that Black people in every state remain far more likely to be arrested for cannabis possession than white people, even in states where the substance is legalized. Though arrests did decrease after legalization and decriminalization, the report found that the racial disparities in arrests persisted.

“To substantially shift the experiences of people who use drugs in their communities, decriminalization must be coupled with meaningful police reform and efforts to build-up systems of support and care,” Leo Beletsky, director of the Health in Justice Action Lab at Northeastern University’s School of Law, told Political Report. “This is because police take advantage of wide discretion, continuing to surveil and control people who use drugs.”

—

Oregon has a trailblazing reputation in the realm of drug policy reform. In 2014, it became the fourth state to legalize cannabis. Then in 2017, it reclassified small-scale drug possession from a felony to a misdemeanor, which decreases penalties but does not apply to people with prior felony convictions. With all these wins, outright decriminalization was the next logical step for reformers.

A separate ballot initiative in November, Measure 109, aims to establish licensed psilocybin (“magic mushrooms”) treatment centers, making it the first state to allow for the legal cultivation and sale of the substance for medical purposes.

Advocates now hope that adopting these new reforms in Oregon could start a domino effect, akin to the one in favor of cannabis legalization, and start a national decriminalization trend. In July, the Drug Policy Alliance released a detailed framework for decriminalizing drugs at the federal level.

There is indeed wide support for a new approach to criminal justice and drug policy in America. A 2018 poll found that three quarters of Americans believe the criminal legal system needs significant improvements, and 85 percent believe the main goal of the system should be rehabilitation. A 2014 report by Pew Research Center found 67 percent of people think the government should focus more on treatment for people who use illegal drugs like cocaine and heroin, compared to just 26 percent who think prosecution of drug dealers should be the priority.

Oregon will soon find out whether the protests and uprisings against police have amplified support for ending the war on drugs.

“Throughout the war on drugs, this has been continually used to hold down these communities and gut them of economic opportunity and resources,” Sutton, of the Drug Policy Alliance, said. “People are really seeing that now.”