Political Report

How Ohio’s Racial Justice Movement Won Big at the Ballot Box

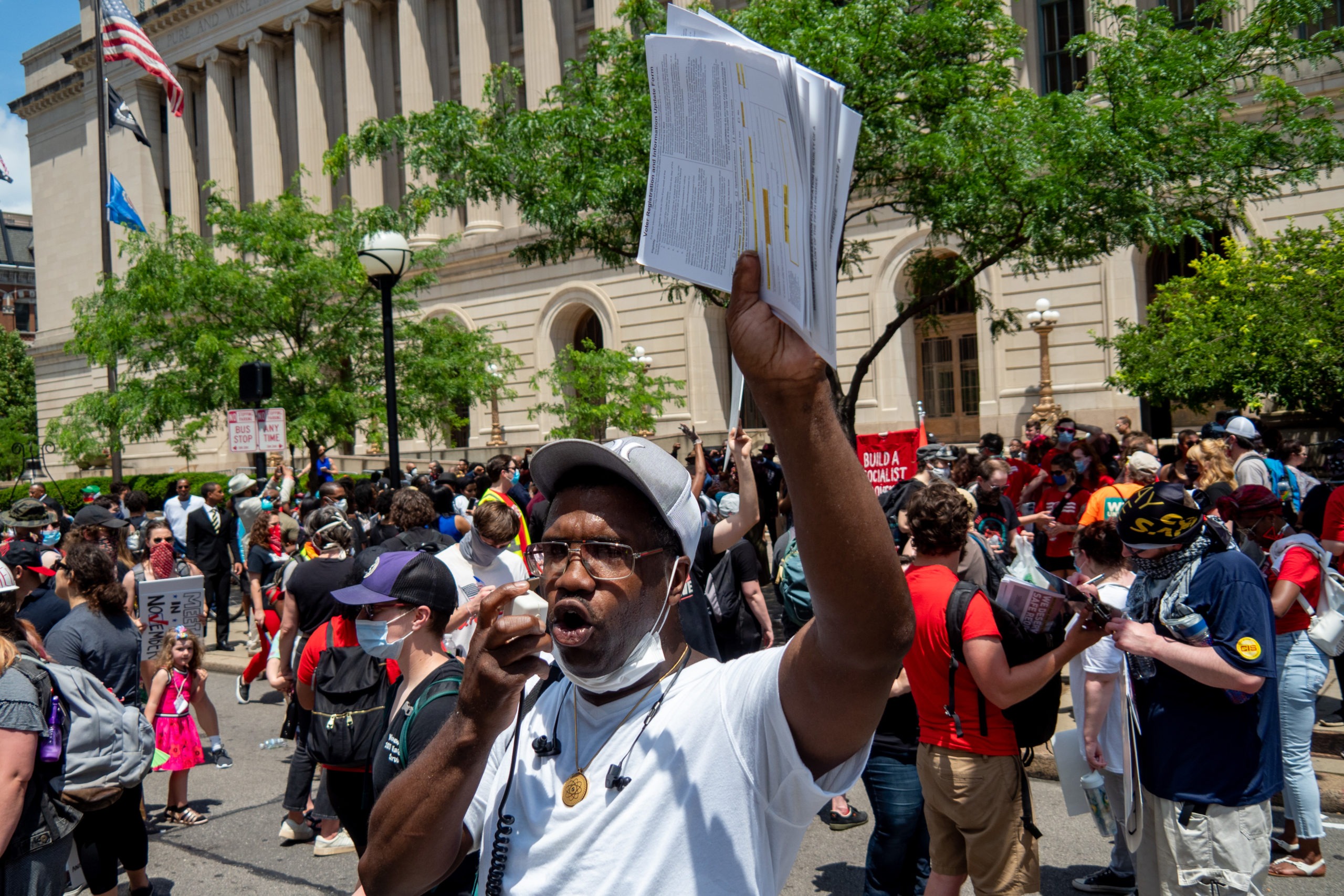

Years of grassroots organizing helped overhaul the criminal legal systems in Cincinnati and Columbus this November. Activists are already looking ahead.

Years of grassroots organizing helped overhaul the criminal legal systems in Cincinnati and Columbus this November. Activists are already looking ahead.

Daniel Hughes had an awakening years ago when police in his hometown of Lima, Ohio, killed a Black woman named Tarika Wilson and shot her infant son.

“At the time, there were folks who were talking about how no one will ever remember her name,” said Hughes, who is now a pastor at Incline Missional Community Church in Cincinnati’s Price Hill neighborhood. “And I remember thinking ‘I will never forget her name,’ because it just awakened something in me.”

So when a University of Cincinnati police officer killed Samuel DuBose, an unarmed Black man, in 2015, Hughes decided to get his congregation involved in the fight for racial justice. They joined the Amos Project, a federation of congregations throughout the greater Cincinnati area committed to improving the quality of life for all residents. Amos is among a number of local groups that have made strides in recent years toward criminal justice reform, which contributed to a significant political shift in November.

In Ohio, where President-elect Joe Biden lost and Democrats fell short of flipping the state Supreme Court, local elections in two counties delivered progressive wins that have potential to transform the criminal legal system. Hamilton County, home to Cincinnati, now has a sheriff who wants to lower incarceration rates, along with a slate of new reform-minded judges—though voters also narrowly re-elected a prosecutor who makes frequent use of the death penalty. In Franklin County, where Columbus is located, voters elected Democrats for every judicial seat on the ballot, approved a civilian police review board, and ousted a notoriously harsh prosecutor.

These wins mirror others in cities and counties nationwide, where voters embraced local candidates and ballot measures that promised progressive change, particularly on criminal justice issues like drug policy and policing. The shift highlights how grassroots organizing and coalition-building outside of four-year election cycles can expand electoral power. And it shows how focusing on down-ballot races can engage voters in ways that national elections may not, because it’s often clearer how the outcomes will directly affect people’s everyday lives.

In 2018, Celeste Treece, a criminal justice organizer with the Ohio Organizing Collaborative, was focused on raising awareness about judicial elections in Hamilton County. “A lot of people didn’t even realize that we elected judges locally,” Treece said.

That year, Democrats flipped two seats on the First District Court of Appeals and picked up two seats on the Hamilton County Common Pleas Court, which handles criminal and civil cases.

To build on the momentum after the 2018 election, Treece and a group of friends started a court watch program to monitor judicial proceedings. Meanwhile, they continued talking to people in the community about the role of the courts and how judges were selected.

“[Often] we only think about the criminal side, but there are a lot of civil matters that go through the courts, like child support and [debt collection],” said Treece. “Many people are going through those things and really don’t understand how the courts affect them.”

Information gathered during the court watch program helped inform Treece’s outreach during the 2020 election cycle. Treece and her team were able to organize small group Q&A sessions with judicial candidates so that voters could ask questions in an intimate setting. Treece also said the national conversation around federal judicial appointments motivated people to learn more about local judges.

Although judicial races are nonpartisan in Hamilton County, Democrats invested in them like never before, winning nine out of 13 open seats in the appeals and common pleas courts in November. The slate included candidates with experience as public defenders and civil rights lawyers, who promised reforms like overhauling the bail system to reduce pretrial incarceration. In an interview with Cincinnati NBC affiliate WLWT, attorney Bill Gallagher credited racial justice protesters for the election of a slate of judges more reflective of the communities they serve. “What was being demanded by people attending those protests was more accountability, more change, more access, more fairness,” said Gallagher.

Prentiss Haney, co-director of the Ohio Organizing Collaborative said the political shift in Hamilton County this year was due to multiple cycles of organizing that have gotten more people involved in local elections. He pointed to the efforts of faith leaders in 2016 to mobilize voters around Preschool Promise, a local ballot initiative that levied millions of tax dollars to fund near-universal preschool and other education programs. And he said that the momentum for political change in Hamilton County can be traced back even further, noting the role of the Amos Project, which has been around for 26 years.“The arc of the wins in Hamilton County has been connected to that base over the years,” he said.

In 2018, Hughes, the Cincinnati pastor, was involved in The Amos Project’s effort to pass Issue 1, a proposal to decriminalize low-level drug offenses. Although it did not pass, the group was able to build on that previous work as it started organizing in 2020. “There’s a sense of certainty [with faith institutions], a regularity around the practices, the ritual,” said Hughes. “The ability to bring people to an awareness, to bring people to a moment is intrinsic in faith communities.”

This year, the Amos Project held forums with Hamilton County sheriff candidates. Hughes said voters ultimately supported Sheriff-elect Charmaine McGuffey because she made significant commitments to reform the office. In April, McGuffey beat incumbent Jim Neil by a landslide in a Democratic primary election, running on a platform that included addressing poor jail conditions and opposing a jail expansion. In the general election, she won against Republican Bruce Hoffbauer, who attempted to stoke fear among voters by equating racial justice protests with violence and chaos.

Hughes referenced the recovery pod program that McGuffey spearheaded when she was a major in the sheriff’s department as an example of her leadership in improving jail conditions. The program began as an effort to help women with substance use disorder transition to life after incarceration. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the program was expanded to offer services to men.

“Someone like McGuffey gives us the opportunity to start to build on the kind of vision or future that we want,” Hughes shared.

But winning elections alone is not enough, he cautioned. For Hughes, building a winning coalition of voters is about getting people to stay involved in strategic organizing for equity and justice.

“What I’m doing right now is I’m trying to get faith communities to recognize the actual power that they have, and name the things that they actually want to create in the world, versus just chasing after an election,” Hughes said.

In Franklin County, Adrienne Hood has a similar perspective. A prominent local figure in the fight for racial justice and police accountability, Hood said the defeat of the county’s chief prosecutor, Ron O’Brien, shows that voters want to change the way Black and Latinx people are treated in the criminal legal system. But she also acknowledged that it takes more than one election to achieve that.

In 2016, Hood’s son Henry Green was killed by two plainclothes Columbus police officers. O’Brien did not prosecute the officers, a pattern that was characteristic of his office. That year, O’Brien faced his first electoral challenge in 16 years. He won, but it set the stage for the renewed effort to remove him from office this year.

O’Brien’s inaction led Hood to become more active in community organizing with groups like the Ohio Organizing Collaborative and The Freedom BLOC, a Black-led organizing effort focusing on civic engagement and electoral organizing in the cities of Cleveland, Columbus, Youngstown, and Akron.

Hood recalled the moment she learned O’Brien had been defeated. “There’s accountability sooner or later,” she said. “I was glad that this time around [O’Brien] was seen for who he is.”

But she was less enthusiastic about his replacement, retired judge Gary Tyack, who hasn’t taken a strong stance on certain reforms, like ending cash bail.

“It’s definitely time for a change in that office, and I’m praying that this is a beginning,” Hood said. “I don’t look at Tyack as my savior, but it is definitely a start in the right direction … that has to be attributed to the grassroot organizations that are making the connections for the community.” She explained that when George Floyd’s murder at the hands of Minneapolis police sparked protests nationwide, organizers in Franklin County channeled the outrage toward electoral action by educating protesters about O’Brien’s connections to the Fraternal Order of Police.

In addition to ousting a longtime prosecutor, voters in Columbus overwhelmingly approved the formation of a civilian police review board.

Hood says the actions of the Columbus police made the best case to the public for the civilian police review board. During this spring’s protests, the police pepper-sprayed several Black elected officials including U.S. Representative Joyce Beatty and Columbus City Council President Shannon Hardin.

“It is very unfortunate that it took three of the top Black officials here in Columbus, in Franklin County, to get [pepper-sprayed] in order to [say] that stuff has to change,” Hood said.

After that incident, Hood said the conversation of a police review board took greater urgency. “It is something that has been recommended for years.” Hood said, recalling a community elder who told her that the fight for a police review board dates as far back as the 1980s.

The energy motivating voter turnout also showed up in Franklin County judicial elections, with Democrats sweeping all eight open seats in the Commons Pleas Court, including the domestic and probate divisions. In an interview with the Columbus Dispatch, Judge-elect Andy Miller said candidates talked more during this election cycle about substantive issues. “I noticed people are more appreciative of the concept of restorative justice,” he said.

With the election over, Hood says the work of groups like Freedom BLOC continues through conversations and community education. “Now, the real work is ahead of us,” she said. “That is educating and empowering the people of our community so that they know the responsibility in holding elected officials accountable does not start nor stop at the ballot box.”