Political Report

Ohio Will No Longer Sentence Kids to Life Without Parole

“We now have hope that our loved ones and family members will someday come home to us,” one advocate said of the new law.

“We now have hope that our loved ones and family members will someday come home to us.”

This article is part of our series on state reforms on youth justice.

Ohio is expanding access to parole hearings for people who have been incarcerated ever since they were children. It will no longer sentence minors to life without the possibility of parole, and it will significantly curtail sentences that effectively amount to the same.

Youth justice advocates are celebrating Senate Bill 256, which was signed into law by Governor Mike DeWine on Saturday, as their latest win in nationwide efforts to keep kids from spending their life in prison.

The law is a “huge sea change” for the state, said Kevin Werner, policy director at the Ohio Justice & Policy Center, because “it recognizes that people change. … The heart of the bill is that Ohio values redemption over excessive punishment.”

SB 256, which is retroactive, only affects parole eligibility; it does not guarantee that people actually get released, even after spending decades in prison. Under the new law, people who committed a crime as a minor will be eligible for parole after no more than 18 years of incarceration if the crime did not involve a homicide, or after no more than 25 to 30 years if it did. That’s longer than in other states that have recently adopted similar laws.

Ohio’s parole board, which has faced heavy criticism, will determine the fate of parole petitions and whether the reform offers genuinely “meaningful opportunities to obtain release,” as the U.S. Supreme Court has put it.

Still, SB 256 will give many people serving life sentences at least some chance at leaving prison.

“The signing of SB 256 means everything to us,” said Stefanie Tengler, an advocate who championed the bill. Tengler’s partner, Joshua Wade, is serving a life sentence after being convicted of murder as a minor. Wade will now be eligible for parole about three decades earlier than he would have without the law

“We now have hope that our loved ones and family members will someday come home to us,” Tengler said. “And for those who were told as teens that they would die in prison, this bill means absolutely everything, too.”

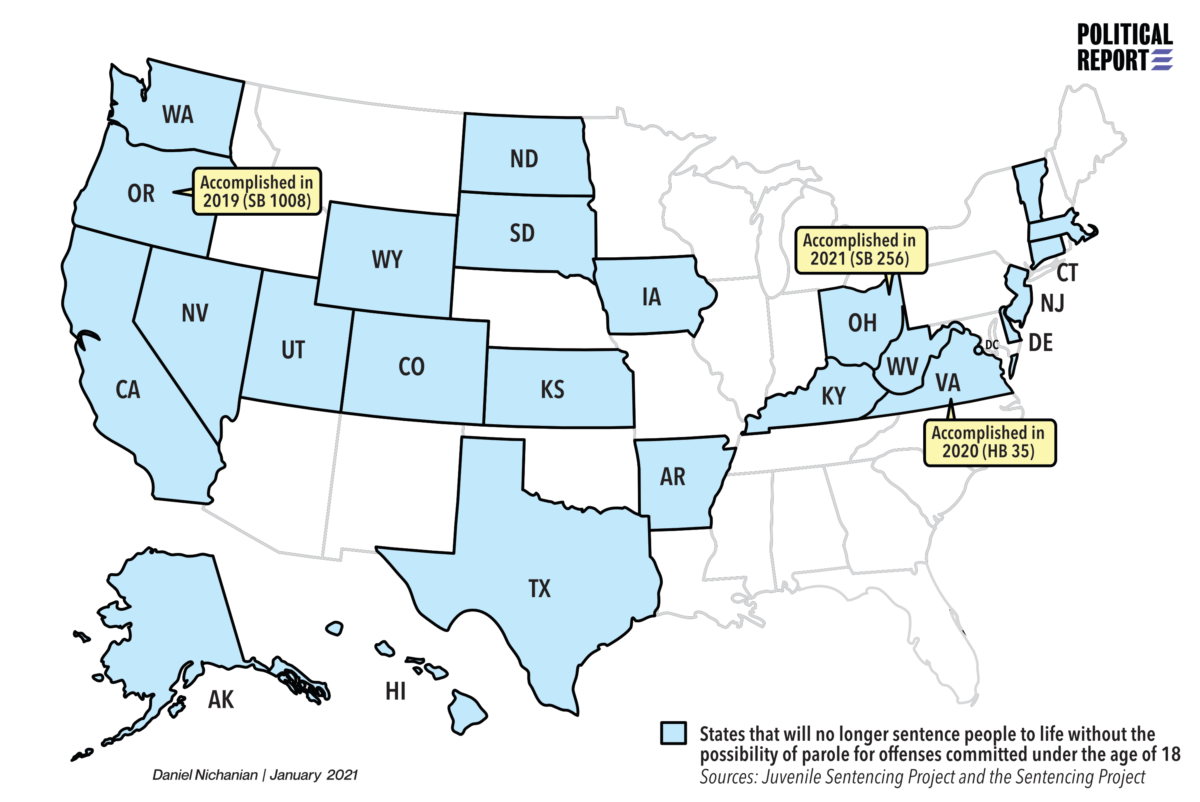

Ohio is the 24th state, plus D.C., that will stop imposing sentences of juvenile life without parole. A wave of states have adopted similar reforms since the Supreme Court ended mandatory life without parole sentences for minors in a series of early 2010s rulings. Oregon, in 2019, and Virginia, in 2020, did this most recently.

Brooke Burns, who heads the Ohio Public Defender’s Juvenile Department, stresses that SB 256 will also help the state confront significant racial inequalities in its prison population. “When we think about lengthy sentences, it’s overwhelmingly kids of color who are impacted by that,” said Burns.

These inequalities stem from disparate sentencing, but also the rate at which children of color are transferred to adult court in the first place, especially in counties such as Cuyahoga (Cleveland) that do so very aggressively.

The Appeal reported in 2019 that the office of Prosecuting Attorney Michael O’Malley has been transferring minors to adult court far more than other Ohio jurisdictions. Ninety-four percent of those who were transferred to adult court in 2018 were Black.

—

Ohio’s Legislative Services Commission estimates that 50 to 60 people will immediately become eligible for parole when SB 256 becomes effective; this is approximately the number of people who have served at least 18 years, and in some cases much more, of the sentences they received when they were minors. Many more will become newly eligible for parole in subsequent years.

The law will apply to most people who are serving outright sentences of life without parole, but also to people whose sentences are functionally equivalent since their parole eligibility was set so far in the future.

“SB 256 acknowledges that science has been at odds with how judges have sentenced youth in the past,” said Claire Chevrier, policy counsel at the ACLU of Ohio, referring to studies that show that the brain develops well into one’s 20s. “Science tells us that young people are not static. … It doesn’t make sense to punish forever something that a youth committed when they didn’t have all the skills necessary to behave like an adult.”

But Werner says that waiting 18 to 30 years for parole eligibility is still harsh. “It would have been better if those time periods weren’t quite so long,” he said. Although that is in keeping with many states’ reforms, recent laws adopted in West Virginia and Oregon make people convicted as minors eligible for parole after 15 years of imprisonment; Virginia last year set the threshold at 20 years.

In addition, states such as California have extended eligibility for reforms meant to treat youth differently above age 18 since young adults are also still developing. In December, the D.C. Council passed legislation to enable people with very lengthy sentences to petition for early release for crimes committed up to age 25. Some advocates are working to abolish life without the possibility of parole sentences for anyone, with no age restriction.

The Ohio law also comes with carve-outs. Youth convicted of killing at least three people, or convicted of homicide tied with terrorism charges, will not be eligible for parole any earlier than their sentence permits, even though going forward minors can no longer be sentenced to outright life without parole. This means that T.J. Lane, who killed three people in a school shooting in 2012 and was sentenced to life without parole, will continue to not be eligible.

One day before DeWine signed SB 256, the Montana Supreme Court ruled that a man serving a sentence of life without parole for a triple homicide he committed at age 17 should be granted a resentencing hearing. Chief Justice Mike McGrath wrote an accompanying opinion that urged the majority to “go further” and to outright hold “that all life without parole sentences are per se unconstitutional for juvenile offenders” due to “the Montana Constitution’s explicit protections for juvenile offenders.”

In Ohio, even for those who will fall under its purview, the practical effect of SB 256 will largely depend on the state’s parole board.

The Legislative Services Commission has already projected that the board will reject most of the parole petitions it considers. (People denied release will get another hearing no less than five years later.)

“It’s an uphill battle for anyone going in front of the parole board,” warned Niki Clum, legislative liaison for the Office of the Ohio Public Defender. She says she is “optimistic” that the people covered by SB 256 will “get a fair shot,” though, in part because the law spells out factors that the board must consider regarding people’s youth and growth.

The parole board has been denounced for its lack of transparency and its stringent standards toward even minor infractions that people accrue while in prison. Werner says that it is prone to “arbitrary” decisions.

Last year, a pair of Republican senators who also backed SB 256 introduced separate legislation that would make the Ohio Parole Board less secretive, but that bill did not move forward.

This is a “big piece of unfinished business,” said Werner.

Ohio advocates also hope to change the statutes that govern how children are transferred to adult courts in order to keep more minors in juvenile courts and avoid the very lengthy sentences that come with adult prosecutions. An earlier version of SB 256 targeted those issues, and would have reduced the sentences issued in the first place, but those provisions were dropped in the version that passed, which focused on parole eligibility.

Burns says that, given the emerging “realization that kids are different,” it is important to consider “those same factors… on the front end” of charging and sentencing as well.

—

In Oregon and Virginia, the two states that most recently adopted laws to end juvenile life without parole, the state government is run by Democrats. But SB 256 had to pass through Ohio’s GOP-run legislature—which it did with wide bipartisan majorities—and get support from the Republican governor.

Clum found that lawmakers from both parties responded to similar arguments. “A lot of people believe in redemption and believe that people, especially children, are capable of change,” she said.

A broad array of other organizations, including the Juvenile Justice Coalition, the Ohio chapter of the conservative group Americans for Prosperity, and the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, championed SB 256. (Some Repubican lawmakers have filed similar proposals in Congress, as have Democratic lawmakers.)

But the Ohio Prosecuting Attorneys Association opposed the bill; members repeatedly testified against it. That is in keeping with many Ohio prosecutors’ staunch opposition to criminal justice reforms. (On Saturday, DeWine also signed a separate bill that many prosecutors fought. It restricts imposing the death penalty on some people with mental illness.)

Prosecutors and other law enforcement officials are also blocking the prospect of similar reform in Illinois, said Jobi Cates, executive director of Restore Justice, an Illinois-based organization that has championed ending juvenile life without parole sentences.

“It’s still a tough haul here,” she said, due to the law enforcement lobby’s influence over the legislature.

But Cates said she was heartened to see Ohio’s reform. Advocates in other states, such as Maryland and New Mexico, are also pushing for similar changes to parole laws. “It helps to have the majority of states moving toward something,” Cates said.