Political Report

New York Senator Makes the Case for Defunding the NYPD

“These changes won’t be made unless we demand them loudly and relentlessly,” says state Senator Julia Salazar.

State Senator Julia Salazar argues in a Q&A that policing reforms “have failed” and that funds should be reinvested into other services; she also lays out bills she is supporting to improve accountability. “These changes won’t be made unless we demand them loudly and relentlessly,” Salazar said.

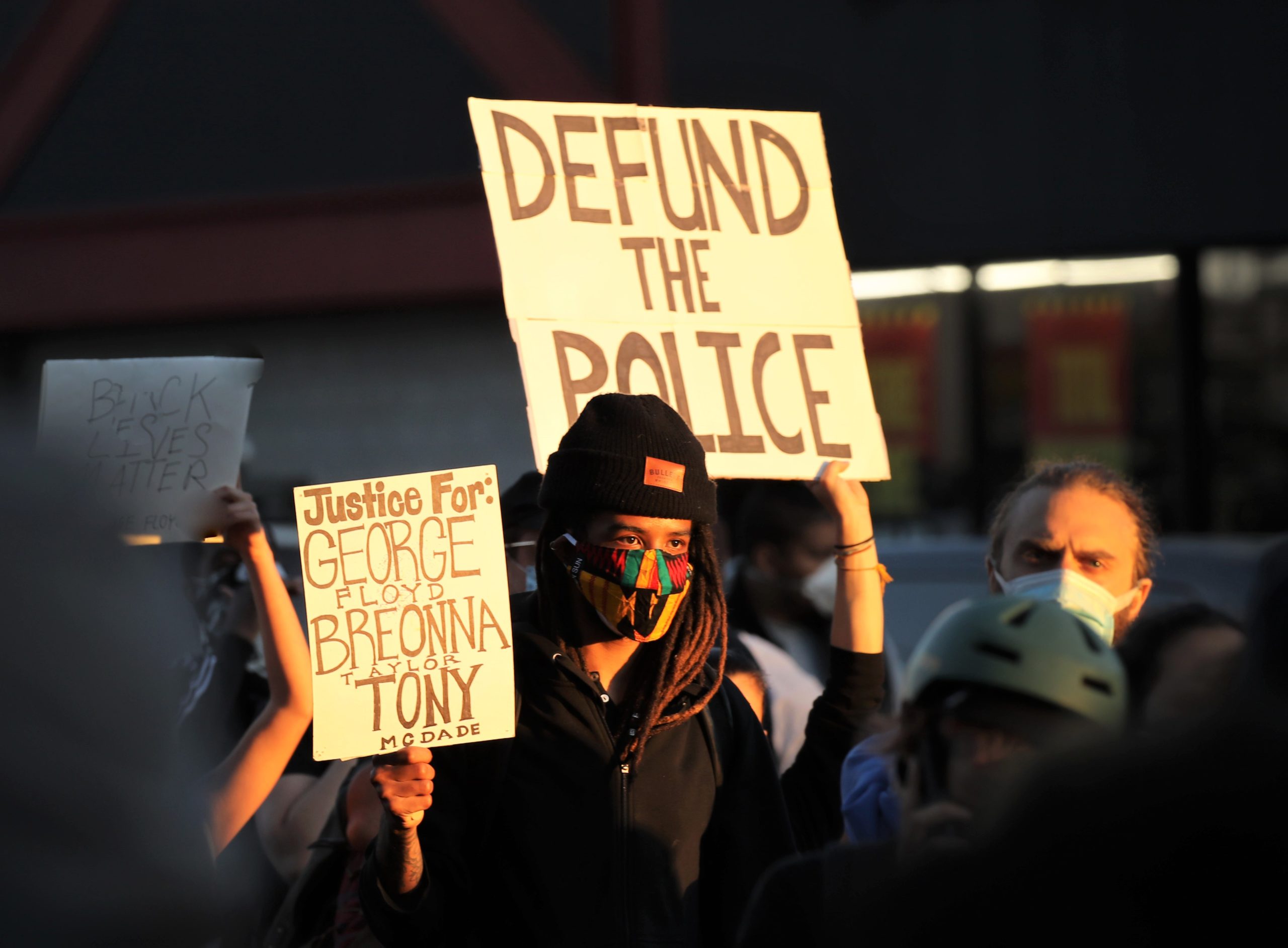

Protesters and advocates called for “defunding the police” during the weekend’s protests over the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other Black people killed by police officers.

Rejecting better training and softer forms of policing as remedies for police violence, they instead focused on substantially diminishing the roles that the police play in U.S. society and questioned the fiscal choices that local and state governments are making. “We must demand that local politicians develop non-police solutions to the problems poor people face,” Alex Vitale, a professor of sociology at Brooklyn College, wrote in The Guardian. “We must invest in housing, employment and healthcare in ways that directly target the problems of public safety.”

Julia Salazar, a Democrat who represents parts of Brooklyn in New York’s Senate, amplified those demands on Friday. “We should call to defund the NYPD,” she wrote in a tweet.

I talked to her in a telephone interview on Sunday about why she would like to see cuts in the New York City Police Department’s $6 billion budget, and about what she sees as steps forward to changing law enforcement in New York State. Our interview took place in the wake of the video of NYPD vehicles driving into protesters, and Mayor Bill de Blasio’s defense of the city’s police.

“I think that attempts to reform the NYPD have failed,” she said, stressing that the solution is not taking “resources in one area or program and transferring them elsewhere in the police department.” She noted, for instance, that asking police officers to stand in as service providers, such as being mental health first responders, has ended up putting people in danger.

Instead, she made the case for “cutting the NYPD’s budget.” She called this “a divest/invest model,” in which resources that the NYPD is “deploying … violently and recklessly” are transferred to public agencies and nonprofit groups to provide social services such as housing programs and mental health care services. Salazar stressed that, with the economic crisis brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, the city is right now eyeing the reverse—big cuts from which the NYPD is shielded.

Before she was elected to the Senate in 2018, ousting an incumbent in the Democratic primary with the support of Democratic Socialists of America, Salazar worked on police accountability issues from the organizing side with Jews for Racial and Economic Justice. That advocacy organization is part of a coalition, Communities United for Police Reform, that is pushing a legislative package meant to increase police transparency and accountability.

Salazar also explained why she supports that package in the course of our conversation, starting with the proposal to repeal Section 50-a, a statute that shields the records of police officers from disclosure. Salazar also defended a bill to diminish arrests over minor violations such as “riding your bike on the sidewalk.” Echoing the criticism of disparate policing that is central to the protests, she said, “If you live in a neighborhood that isn’t heavily policed, it sounds so absurd.”

Salazar acknowledged these demands have long been around, but expressed some optimism. “It has been only due to a lack of political will that these things haven’t happened,” she said, but “the publicity of this particularly heinous incident and the attention that people are paying to it, including people who maybe weren’t that motivated by racial justice and police accountability before,” may be a “significant difference” from the past.

The interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

—

You tweeted on Friday that “we should call to defund the NYPD.” Can you tell me what that call means to you, and what it would entail in practice?

The NYPD has about a $6 billion budget. Even if we weren’t seeing the justified outrage right now at these incidents of severe police brutality, I think it’s completely unjustifiable that there’s $6 billion allocated to the NYPD. We’re facing an economic crisis in New York, and there are proposals to cut some essential services and programs from the city budget. The city is considering cutting funding to things like the summer youth employment program, which vastly benefits young people of color and gives people employment opportunities they wouldn’t otherwise have. There’s also threats of cuts to health care services, even at a moment when they’re more desperately needed than ever. In light of that, it’s even more important that we consider, do we need to be giving the NYPD $6 billion?

I think we need to consider a divest/invest model. When we look at their resources, and how they’re deploying them violently and recklessly, it makes the case even stronger for reducing their budget, and then using those funds for social services, and specifically for things that New Yorkers would want the police to do but the police are not currently doing: harm reduction, community-based public safety.

That’s the sort of thing grassroots organizations have been doing for a while, but every year they have to fight over scraps or look for funding from different sources just to sustain themselves, while the NYPD has this ongoing line item in the budget. I’m not in this City Council or in the mayor’s office, but I know that council members, whose take on it is actually consequential, are seriously considering reducing the budget.

To clarify, when you talk of steering money toward harm reduction and community-based public safety, are you suggesting providing services outside of law enforcement agencies, or are you suggesting that law enforcement agencies should be better focused on those goals? If the former, what kind of programs and services do you think should be empowered?

I think that attempts to reform the NYPD have failed—attempts to provide de-escalation training, to train officers on emergency, mental health first aid. We could cite a lot of examples in the past few years of how attempts to change the way NYPD does policing and public safety have failed. I don’t think community policing has been successful either. It’s either because the attempts have been insincere, and we still see officers who have no stakes in a community, no real relationship to a community, being assigned to police that community, or simply because just because an officer from Bed-Stuy for example does not mean that they are going to treat Bed-Stuy residents with the respect that that people deserve. It doesn’t nullify the importance of de-escalation training, or ensuring that the patrol guide is instructing officers to exhaust all nonviolent actions before using their weapon. It doesn’t nullify the importance of policies within the department.

But I don’t have a lot of faith in reforming the NYPD, or taking resources that are in one area or program and transferring them elsewhere in the police department. I think that, instead, we should be cutting the NYPD’s budget and then transferring the cost saved from those cuts to nonprofit organizations, transferring them to a city agency that can provide adequate mental health care services for people and other social services.

Especially considering how much time the NYPD spends policing quality-of-life crimes that are related to issues that other agencies or organizations are seeking to address. I would be really interested to see the funding that’s directed to NYPD enforcing loitering laws or managing people experiencing homelessness and directing them to shelters, and the different ways that they respond to people living on the streets or in the subways that could instead be used to provide people with at minimum temporary housing. And it provokes another question, is the most cost effective solution to homelessness in the long term to just provide people with permanent housing? That’s something that I do believe.

So part of what you’re saying is that social services should not be provided by people who also have a law enforcement hat.

Absolutely. I don’t think that the NYPD should be first responders. If for example I called 911 and said I’m with this person who is having a mental health crisis, often NYPD officers will be the ones who are sent to respond, and we’ve seen many cases in which that ends in physical violence for the person who was seeking help. So-called emotionally disturbed people, as the NYPD refers to them, people who are in crisis, who are not armed with any kind of weapon, end up being victims of police brutality.

One example comes to mind: the Bard Prison Initiative, a program for people who are incarcerated. What programs like this have demonstrated is that when you provide people with services and opportunities for them to be empowered, pursue their interests, to learn to develop, and to be supported, that drastically lowers the recidivism rate. Within the NYPD’s $6 billion budget, there is some funding already allocated to social services, and yet I don’t see at least any measurable benefit from the NYPD being the ones who distribute those services to people.

You’ve said a few times that reinvesting policing funds elsewhere would specifically improve the metrics for which we typically turn to policing, such as harm reduction, safety, or recidivism. Can you talk more about that?

The underlying question here is, does the presence of the NYPD make people in Black and brown communities generally feel safer? Looking at how resources are spent geographically in the city, it certainly appears that more officers are deployed in Black and brown neighborhoods. What measurable impact do we see from that? Because if we’re not seeing a proportionate decrease in violent crime, or a decrease of certain risk factors that ostensibly the police is supposed to be able to address related to public safety, if we’re not really able to demonstrate that—and I don’t think we could demonstrate that more police has generally made our communities safer. There are people in my district, to be clear Black and brown people, who are not necessarily thinking about alternatives to the police in terms of public safety. But I know that there are some who definitely think about it, and who do not feel safer when they see police officers in a subway car, or outside the turnstiles and in the train station, or just patrolling outside of the public housing development.

I have 25 public housing developments in my district; the city spends enormous resources on policing public housing residents, and being a constant presence in public housing developments, to an extent that many of the residents are either uncomfortable with or they’re not seeing the benefits. That’s something that I think should be completely reevaluated in terms of how the city spends money.

I’ve asked you about New York City’s budget, but you of course hold office at the state level, where there have been similar budgetary debates. In March, you voted against a section of the state budget, which made important spending cuts, although the state’s correctional budget has been comparatively shielded. Is New York State prone to the same unbalance you described at the city level?

I voted no on the policy bills in the New York State budget this year, and one of the biggest reasons was because of the inclusion of these rollbacks to bail reform and discovery reform that were passed in 2019. So in 2019 we passed legislation that we knew would lead to dramatically fewer people being detained and incarcerated pretrial, and making the discovery laws more reasonable for the defense and for someone accused of a crime. And then due to baseless hysteria before the new bills were even implemented—from the right, from DAASNY, from law enforcement interests—this blowback against the reforms provoked the state legislature and the executive to try to roll back these reforms. The rollbacks amount to an expansion of wealth-based detention: More people are going to be detained via cash bail pretrial.

And that is going to be at additional cost. There is a fiscal impact to increasing the prison population, especially amidst a pandemic that for the sake of public health demands social distancing. And so it’s very frustrating that that has been a priority in the state government, rather than seeking to address some of the underlying issues that lead to people being incarcerated in the first place.

A New York coalition, Communities United for Police Reform, is now pushing for the Safer New York Act, a package of bills that it describes as promoting police accountability and transparency. Days ago you called it “a minimum we should do.” The component that has received the most attention this week is repeal of Section 50a, which prohibits the disclosure of police misconduct records without the officer’s approval. You actually clashed on this with police union leaders last year. What obstacle does Section 50a present to accountability?

This is something that communities and advocates in support of greater police accountability have been advocating for quite a while. Section 50A of the Civil Rights Law was originally intended to protect the privacy of public servants, and instead, in the decades since it became part of New York State law, it has been used by police departments to shield officers from accountability in cases where officers are accused of misconduct or being investigated. It really prevents violent officers from being held publicly accountable. There are multiple bills at the state level that seek to address 50a. One is Senator Bailey’s bill. I’m a co-sponsor of that bill. and it is a full repeal of Section 50a. It would prevent the NYPD from being able to say in court that they don’t have to release disciplinary records of, for example, officer Daniel Pantaleo, who killed Eric Garner, despite the Freedom of Information Act or other transparency legislation.

Another bill would enable the attorney general to investigate and prosecute cases of police killings. Why would transferring jurisdiction to the attorney general help promote accountability, and what else should be done to reduce the killings in the first place?

What this legislation would do is create an office of the special prosecutor, most likely in the attorney general’s office, for prosecuting officers who kill a civilian. The reason that I support this is that I think anytime an officer commits, not only lethal violence against a civilian, but any kind of serious physical violence against a civilian, they should not be investigated by the NYPD. This should be policy for any public servant who is accused of some kind of professional misconduct. It’s a conflict of interest.

Governor Cuomo, years ago, signed an executive order to create this special prosecutor within the attorney general’s office. Since then, there have been some cases that this unit chose to investigate, and the idea is that, if we were to codify this executive order and, additionally, strengthen it so that it’s not limited to only investigating some cases, it would lead to more accountability. It would at least be more likely that families of people who’ve been killed by the police would be able to pursue criminal justice through the courts and not just a civil lawsuit.

There’s also Senator Bailey’s “unnecessary arrest” bill. It would help to end some of the arrests for violations which are minor, noncriminal, ticketable offenses, but where an NYPD officer has the choice of either issuing a summons or arresting a person. This legislation would say you can no longer arrest someone for these minor offenses, things like riding your bike on the sidewalk. If you live in a neighborhood that isn’t heavily policed, it sounds so absurd, but people are still arrested for these things. We need to minimize the number of people who are needlessly arrested and incarcerated and ending up in the system in the first place.

Moments after I read through the bills embedded in this package today, I saw this tweet from Sam Sinyangwe, an activist who works on police violence and accountability: “The problem is not a lack of knowledge or solutions – it’s a lack of political will.” This struck me since many of these proposals have been around for a while. What do you think of that point? What would it take for an overhaul?

Even though I didn’t see the tweet, I agree with the assessment. These bills have existed for a while, advocates have been publicly and very clearly demanded these changes for a while, and it has been only due to a lack of political will that these things haven’t happened.

I have been a legislator just for the past couple of years, a year and a half. Immediately before I ran for office, I worked full time as a community organizer for a nonprofit that was within the Communities United for Police Reform Coalition. And before I ran for office, I was advocating for some of the legislation that we’re now still having to advocate for, and demand that our leadership prioritize it. So I feel the exhaustion with having to do this all over again as an elected official, and I can sympathize with the exhaustion that people feel as civilians or advocates.

I think the difference is that leadership has changed in the past year and a half, and I think that’s meaningful. The state legislature, especially the Senate, changed dramatically in 2018, and effectively in 2019. Then, additionally, things are not getting better; for many people this is a life-or-death issue, and so it is urgent. At the same time, it’s realistic to say that a year is very short in a legislature’s time. And so what’s important is that we act with urgency right now, particularly in this moment, to actually pass these reforms and changes.

But, even though it’s only been a year and a half since Democrats took power in the state legislature, in that time, as you mentioned earlier, there was both passage of the bail and discovery reforms, but then also a roll back this year. There was time for that rollback this year even after the pandemic had begun. So does that raise concerns about political will in New York going forward?

Yeah. I am concerned, and I think we really need to loudly be demanding that this is done and otherwise it won’t be. These changes won’t be made unless we demand them loudly and relentlessly.

Of course it isn’t new for police officers unfortunately to kill Black civilians with impunity, but the publicity of this particularly heinous incident and the attention that people are paying to it, including people who maybe weren’t that motivated by racial justice and police accountability before, I think that that’s a significant difference from when we were negotiating the bail reform and discovery reform laws.

Earlier this week, U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said that, “A lot of politicians are scared of the political power of the police, and that’s why changes to hold them accountable for flagrant killings don’t happen.” What do you make of that factor in New York?

I think it’s important to focus on how the role of police unions and law enforcement as an industry, certainly as an interest, in politics. I think it is highly relevant that this crisis has provoked people to pay attention to how much money even some progressive legislators are taking from law enforcement interests, and to demand that they stop taking that money.

Have you taken money from law enforcement PACs or unions in the past, and will you in the future?

No, I haven’t I haven’t before and I definitely won’t in the future. I recognize that it’s not the entire equation for why politicians are afraid. There are also politicians who are afraid to offend and challenge the police because they have a lot of officers in their district.

But I think that pairing popular rejection of these private interests and politics with a change in the public discourse, of more people recognizing that we need these policies and these changes, that those two things together can be what finally changes it.

This article is part of The Stakeholders, a Political Report series of Q&As with state and local actors on the criminal legal system.