Political Report

New York Ends a Punishment That Traps People in Poverty

A new law will stop the suspension of driver’s licenses when New Yorkers fail to pay fines.

A new law will stop the suspension of driver’s licenses when New Yorkers fail to pay fines, though the governor weakened the legislation before signing it.

On New Year’s Eve, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed into law a bill that will end the suspension of driver’s licenses over a failure to pay a traffic ticket, a major win for economic and racial justice advocates who have long decried the practice. The law will also reinstate the licenses of hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers, many of whom have lost driving privileges because they cannot afford to pay their fines.

Suspending driver’s licenses entrenches and punishes poverty by preventing people from driving to work, taking kids to school, or visiting their doctor during the COVID-19 pandemic. People who are stopped for driving on a suspended license face misdemeanor or felony charges, and arrests of people who can’t afford to pay fines and fees inflate jail populations across the country.

“This win is a significant step toward scaling back economic and racial inequality in New York,” Katie Adamides, New York state director at the Fines and Fees Justice Center, said in a press statement about the new law. (Note: Jonathan Ben-Menachem, the author, was employed by the Fines and Fees Justice Center until July of 2020.) The law was sponsored by Assemblymember Pamela Hunter and Senator Timothy Kennedy.

Advocates are also warning, though, that New York needs to take many other steps if it aims to fight the criminalization of poverty, especially because Cuomo cut out an important part of the legislation before signing it.

After the 2008 recession and the wave of austerity that followed it, local tax revenues dropped and tax increases became less politically viable. As a result, jurisdictions increased the amounts of fines and fees, and they imposed them on more people in order to fund government services. Since fines and fees are not adjusted according to wealth, they’re an inherently regressive form of taxation, and cities with larger Black populations tend to rely more on fines to fund government.

When the 2014 police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, led to a Department of Justice investigation that exposed the town’s racist and extractive policing practices, efforts to reform fines and fees accelerated nationwide. In recent years, advocates have targeted driver’s license suspensions.

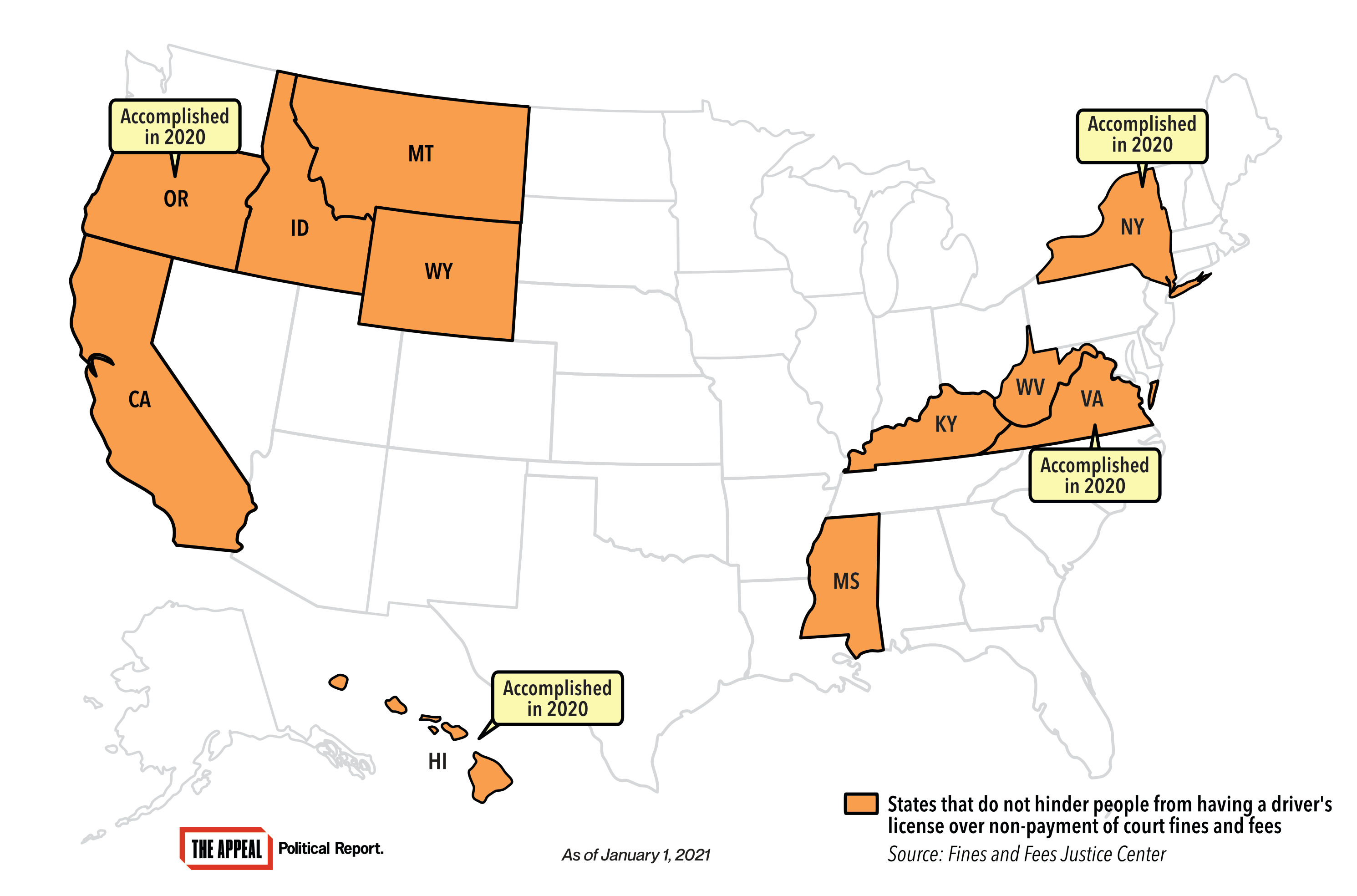

With its new law, New York joins 10 states that have stopped suspending licenses for failure to pay court debt, according to the Fines and Fees Justice Center. Hawaii, Oregon, and Virginia adopted similar laws last year, and others have restricted license suspensions more narrowly as well. (New York, unlike other states, already did not suspend licenses over fines and fees related to criminal convictions as opposed to traffic violations.) Advocates are hoping to get other states such as Texas to join.

Studies undertaken in New York show that driver’s license suspensions for unpaid fines and fees disproportionately target Black and low-income communities, as is true nationally.

According to data released by Driven By Justice, an advocacy coalition that supported the new law, New York ZIP codes with lower average incomes and fewer white residents tend to see dramatically more suspensions. In New York City, where driving on a suspended license is one of the most-charged crimes, 80 percent of all those who are arrested for this offense are Black or Latinx.

The inequitable impact traces back to the fact that Black and Latinx drivers are pulled over and ticketed at higher rates, making them more likely to accrue debt and have their license suspended. New York courts are among the most aggressive in the country when it comes to traffic tickets. In Buffalo, for example, police issue seven times as many tickets for tinted windows as they do for speeding; drivers even told the Investigative Post in 2019 that they had received a separate ticket for each tinted window. Those multi-ticket stops are most common in Black neighborhoods.

The new law does not eliminate all driver’s license suspensions related to traffic tickets, however.

The bill that had initially passed the legislature would have also ended suspensions for a failure to appear in court for traffic hearings. But in late December, the governor’s office requested a chapter amendment, which the legislature agreed to, removing this provision.

In a memorandum explaining the carve-out, the governor wrote: “Allowing drivers to simply ignore their tickets will inevitably allow for scofflaws to remain on the roads, and present a health and safety hazard to the public.”

But a failure to appear in court is connected to poverty as well. People who can’t pay a traffic ticket may also not be able to take time off work to go to court, or may be unable to arrange child care. Those who can afford it can pay off their fines without the need to show up in traffic court.

“Driver’s license suspensions for failure to appear only punish poor New Yorkers who can’t afford to take time off of work to appear in court,” Scott Levy, chief policy counsel at Bronx Defenders, told the Political Report. “The state is shooting itself in the foot by not ending these suspensions for failure to appear. It means that thousands of people across New York will not get the benefit of being able to drive to work without the fear of being arrested.”

Under the new law, people who miss their court appearance will be afforded a 90-day grace period before their license is suspended, and two notifications will be sent by mail or digital communication. The new law also imposes a moratorium on all criminal charges for driving on a suspended license (when the suspension stems from failure to pay or appear) between Jan. 1 and July 1, when the state will implement a new system to offer payment plans to people who cannot afford their traffic tickets.

The cumulative effect of driver’s license suspensions in New York has been enormous. Between January 2016 and April 2018 alone, there were almost 1.7 million driver’s license suspensions in New York for both nonpayment of traffic fines and non-appearance at traffic hearings.

The new law also still allows suspensions for nonpayment of fines and fees for drivers who violate vehicle height or weight restrictions. These account for less than 1 percent of tickets statewide and mainly impact drivers of large trucks and construction vehicles.

Beyond tickets and driver’s license suspensions, advocates have pointed to a broad array of potential fines and fees reforms in New York. The No Price on Justice coalition is calling for the abolition of all state-imposed court fees, commissary garnishment for court debt, arrests and incarceration for nonpayment of fines, and mandatory minimum fines.

State lawmakers have introduced legislation to address several of the coalition’s policy goals. In the last session, one bill would have abolished a wide range of court fees, including the mandatory surcharge attached to criminal convictions. It would have ended commissary garnishment and debtors’ prison practices, too. Another bill would have required all state prisons to provide free phone calls for incarcerated people for a minimum of 90 minutes per day; currently, incarcerated people must pay exorbitant sums that they often cannot afford in order to get in touch with their families. It’s likely that these bills will be reintroduced in the 2021 session.

Democrats made legislative gains in New York in 2020, including securing a newly veto-proof majority, which may ease passage for progressive legislation in the upcoming session.

Some advocates hope that this new landscape will encourage politicians to take up even more ambitious transformations of the state’s fiscal policy.

For example, the state property tax cap—a policy long pursued by Governor Cuomo—prohibits local governments other than New York City from raising property taxes by more than 2 percent each year. Municipalities that have few ways to raise revenue may then end up resorting to fines and fees. Abolishing the property tax cap would give municipalities another option.

“While recent reforms like ending driver’s license suspensions for unpaid traffic tickets are steps in the right direction, New York is long overdue for much broader fines and fees reform,” Adamides, of the Fines and Fees Justice Center, told the Political Report. “Until the state ends its reliance on fines and fees for revenue, we will continue to see the extreme harm that these regressive taxes cause to those least able to afford them.”

—

This story has been updated to reflect the author’s past employment with the Fines and Fees Justice Center.