Political Report

New Mexico D.A.s United to Torpedo Reforms. The 2020 Elections Could Breach That Unanimity.

The June primaries may give reform advocates new allies for ideas they have championed, for instance on drug policy, parole, and voting rights.

The June primaries may give criminal justice reform advocates new allies for some of the ideas they have championed, for instance on drug policy, parole, and voting rights.

Progressives hoped that Democrats’ 2018 takeover of the New Mexico state government would overhaul its criminal legal system, but they quickly ran into the political juggernaut of state prosecutors.

One promising bill would have lowered drug possession charges to the level of misdemeanors, significantly reducing penalties. Five states have done this, including conservative Oklahoma. Days after Senate Bill 408 made it out of committee, though, the New Mexico District Attorney Association (NMDAA) released a statement against it approved by all of the state’s DAs; it died soon after.

When a bill restricting felony disenfranchisement made it out of committee that same week, DA Dianna Luce, who presides over the NMDAA, called voting a “privilege” rather than a “right” to reject the idea of enfranchising people while on probation and parole. Though three other newly Democratic states did just that last year, New Mexico’s version did not get a vote on the floor.

Reformers’ most stinging defeat came when Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham vetoed House Bill 564, an overhaul of probation and parole rules, shortly after all 14 DAs jointly lobbied her to kill it. It would have increased the state’s burden to justify denying parole to people in prison for decades and reduced the use of incarceration as a sanction when people violate probation or parole conditions.

“We passed [HB 564], and they torpedoed it,” Representative Antonio Maestas, the Democratic lawmaker who sponsored it, told me. “Because they’re so fixated on penalties and incarceration as a deterrent, their only policy initiative is to increase penalties and run bills to increase penalties.”

“The DA association here in New Mexico has been very disruptive when it comes to realizing meaningful reform,” said Barron Jones, senior policy strategist at the ACLU of New Mexico. “They are very powerful voices.”

The 2020 elections, which kick off in three weeks, on June 2, will not alter the politics of state DAs overall.

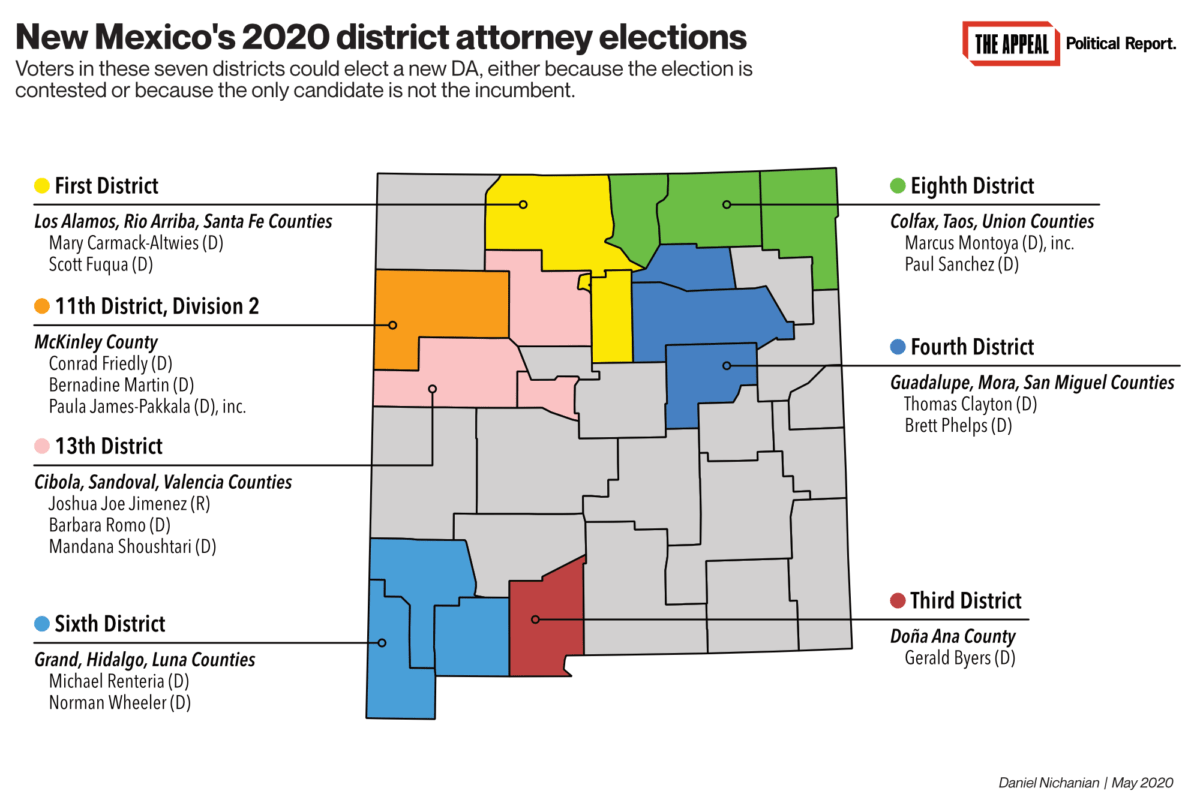

Although all 14 DA offices are up for grabs, the only candidates running in most of these races are the incumbents who lobbied against the 2019 bills, or else deputy DAs whose platforms mirror these DAs’ “tough on crime” positions. Some are even calling for harsher laws, though the state’s incarceration rate is far higher than the nation’s already sky-high numbers.

Still, the united front that DAs presented in 2019 may be breached.

Candidates are running in at least two races — the populous First Judicial District (which covers Santa Fe, Los Alamos, and Rio Arriba counties), and the smaller Fourth District (Guadalupe, Mora, and San Miguel counties) — on promises to bring some change. In interviews, they expressed support for some of the reforms that the state’s DAs fought against last year.

These races may give the state’s reform advocates new allies for some of the ideas they have championed.

—

Last week, I contacted all non-incumbent contenders running in New Mexico to gauge their views on the bills that current DAs opposed, as well as on broader reform proposals. Many did not reply; others shared positions that were aligned with the state’s prosecutorial status quo.

But three candidates broke with that status quo on at least some matters: Mary Carmack-Altwies and Scott Fuqua (First District), and Brett Phelps (Fourth District).

In both districts, the incumbent DAs are not seeking re-election and their replacements will be decided in the June 2 Democratic primary. (No Republicans filed to run in either race.) Phelps faces Tom Clayton, a deputy DA who did not answer a request for comment. By contrast, in the First District, Carmack-Altwies and Fuqua are the only candidates running.

Phelps, a public defender, told me he was already active last year in advocating for the reforms that faltered, and that he had traveled to the capitol to do so as a member of the state’s Criminal Defense Lawyers Association. He would keep that up if he were elected DA, he said. Although he would represent one of the state’s least populous jurisdictions, he made the case that his win may change statewide dynamics by at least introducing one alternative perspective. “It really is a significant voice in this discussion to be one of 14 elected DAs,” Phelps said. “That would amplify the message at a statewide level.”

Fuqua echoed that point. “The opposition to reducing possession to misdemeanor offenses feels like a vestige of the war on drugs to me,” he said. “If [SB 408] came up again, and I’m in the DA’s office, it’ll be 13 to one, unless I can convince other people to come on board with it.” His opponent, Carmack-Altwies, agrees with him on this issue. “Those are easy questions for me,” she said, laughing, when I asked about her views on SB 408 and also on legalizing marijuana.

All three candidates also indicated support for the 2019 proposal to expand voting rights to at least people who are not presently incarcerated.

Maestas, the lawmaker, agrees that even a lone DA could make a difference. He believes that the 14 DAs’ united front against his probation/parole bill (HB 564) proved decisive last year. (Phelps and Fuqua expressed support for that bill; Carmack-Altwies defended the DAs’ criticisms.)

“They weren’t persuasive, it was just the fact that all of them signed the letter,” said Maestas, who himself used to work as a staff prosecutor. “It was too much to overcome in terms of the public backlash they created. When all 14 DAs signed a letter saying veto the bill, it would have taken a lot of strength from the governor to not do that. They had the bully pulpit.”

—

Elsewhere in the state, away from its First and Fourth Districts, the prospect of new perspectives or for voices that are critical of the status quo are weaker. (Our New Mexico master list contains a database of who is running for DA in each of the state’s elections.)

Luce, the NMDAA president, and Andrea Reeb, its vice president, are unopposed in the Fifth and Ninth Districts. Both are Republicans. Many other DAs are also unopposed, including Raul Torrez, the Democratic DA in the state’s largest county (Bernalillo, home to Albuquerque), and Rick Tedrow, San Juan County’s Republican DA. Tedrow presided over the NMDAA in 2017, during an earlier push against a statewide change, when DAs voiced worries about bail reforms.

In the Third District (populous Doña Ana County), deputy DA Gerald Byers is sure to be the next DA since the incumbent retired and Byers, who declined to answer my questions, is the only candidate on the ballot. A 2019 lawsuit filed by former staffers in the DA’s office alleged that Byers contributed to sex discrimination, and that he ordered them to remove signs from their doors because the phrase on them—“No Mansplaining”—was “sexist against men.”

The incumbent is also retiring in the 13th District (Cibola, Sandoval, and Valencia counties), the state’s second most populous jurisdiction. Joshua Joe Jimenez, a former prosecutor running as a Republican, will face one of two Democratic deputy DAs, Barbara Romo and Mandana Shoushtari. On their campaign websites, Romo and Shoushtari both regret that it is too easy for some defendants to be released pretrial; they include no specific proposals that would promote decarceration. None of the three replied to a request for comment on their views.

The Sixth District (Hidalgo, Grant, and Luna counties) is yet another open race. On his website, deputy DA Norman Wheeler touts the fact that he greatly increased drug-related prosecutions as an achievement, a far cry from others’ aspirations to lessen “war on drugs” practices. Neither Wheeler nor his opponent, defense lawyer and former deputy DA Michael Renteria, replied.

In the Eighth and 11th Districts, finally, DAs Marcus Montoya and Paula Pakkala face challengers in the Democratic primary. Despite their stances on the 2019 bills, their opponents are not pressing them on criminal justice reform. (Here again, no Republican filed.) In email messages, Paul Sanchez (Eighth District) and Bernadine Martin (11th District) indicated views that were in line with the incumbents’ on those legislative proposals; both also expressed concern about the prospect of legalizing marijuana for recreational use. Another 11th District candidate, Conrad Friedly, did not reply to a request for comment.

—

The First District, which includes Santa Fe, is the likeliest to elect a DA who espouses some affinity for criminal justice reform. Both contenders argue for shifting away from the war on drugs and minimizing prison sentences for drug possession. “We’ve been trying to incarcerate our way out of drug addiction for 40 years, and it hasn’t worked,” said Carmack-Altwies, who was a public defender for more than a decade before joining the DA’s office as a prosecutor.

Prison admissions over drug offenses have indeed grown significantly since 2012, an ACLU analysis shows. “Civil possession indicates a public health problem and not a criminal problem,” said Jones, of the ACLU.

The Santa Fe candidates also agreed that people who are on probation and parole should be granted the right to vote, which is not presently the case.

They parted ways on some other issues, though. Carmack-Altwies argued that making it easier for people to be granted parole after 30 years of incarceration would make releases too frequent for people who committed the worst crimes. She also regrets that the state’s bail reform, which she noted she largely supports, may have swung too far in restricting prosecutors’ ability to obtain pretrial detention.

Fuqua, an attorney in the attorney general’s office, raised no concern when asked about the current bail rules, and he broadly defended the 2019 bill on parole grants.

Phelps, the public defender who is running in the smaller Fourth District, took bolder stances on these issues. Besides unequivocally defending HB 564 and SB 408, he argued for ending felony disenfranchisement altogether, describing voting as a mechanism of accountability for officials prone to overcriminalize.

Phelps called on reform advocates nationwide to pay attention to smaller, rural districts like his, even if they are less populated than reform hubs like Philadelphia or San Francisco. “The need for change extends beyond big cities. And the recognition by people of that need for change is not limited to big cities either,” he said.

He added, “I would encourage anybody who’s in a rural area to be vocal about these issues, because for us it’s been a hugely positive response.”

Reform advocates have certainly had some positive responses in recent years. In 2019, New Mexico decriminalized possession of small amounts of marijuana, and restricted the use of solitary confinement against pregnant women, children, and people with mental illness. But even those proposals were very considerably narrowed during legislative debates. Marijuana legalization did not make it through, and a stronger proposal to restrict solitary confinement for all prisoners was hollowed out. New Mexico uses solitary confinement very aggressively, The Appeal has reported.

Maestas was also one of the main sponsors of the bill that restricted solitary confinement. “We have a lot of challenges in New Mexico,” he told me. “Crime is very prevalent, and politicians are still a little leery because of the politics of crime. It’s easy to torpedo criminal justice reform efforts by painting it as soft on crime. It’s more difficult to articulate the truth and convince the voter that criminal justice reform actually lowers crime.”

He added, “But it’s only a matter of time before DAs start winning on criminal justice reform campaigns.”

Explore our coverage of the 2020 local elections.