Political Report

New Jersey Attorney General Bans ICE’s 287(g) Program

Gurbir Grewal terminated existing 287(g) contracts. But immigrants will continue to be treated differently.

Gurbir Grewal’s directive terminates existing 287(g) contracts. But immigrants will continue to be treated differently.

Attorney General Gurbir Grewal acted last week to eliminate ICE’s prized 287(g) program from New Jersey’s landscape.

His new directive terminates two counties’ existing 287(g) contracts and bars other counties from striking such deals in the future. It also expands the circumstances under which counties can cooperate with ICE outside of the 287(g) program, however.

The 287(g) program authorizes local law enforcement officers to research the immigration status of people brought into county jails. Grewal said in a statement that 287(g) contracts create “confusion regarding the distinct roles of local law enforcement and federal agents” and “make it less likely that immigrant victims and witnesses will cooperate with local police in criminal investigations.”

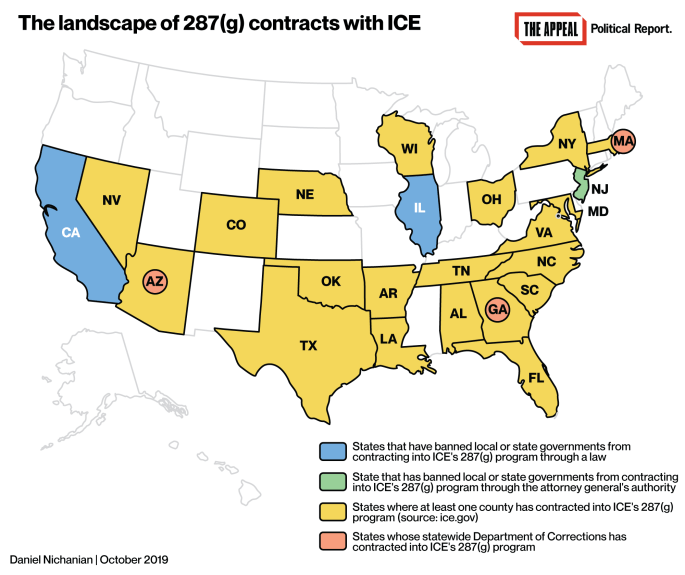

New Jersey is the third state to institute a statewide ban on 287(g), according to Political Report tracking. It is also the first to do this via executive action. California and Illinois adopted bans via the legislative route in 2017 and 2019.

“No jurisdictions should waste their limited resources and personnel time on separating immigrant families, funneling immigrants into inhumane detention conditions, and violating due process rights,” Angela Chan, a leading advocate behind California’s ban and the policy director of Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Asian Law Caucus, told me this week. She called Grewal’s directive against 287(g) “a smart move.”

There are still 20 states where at least one county contracts into 287(g), however.

I reached out to Democratic attorneys general in Colorado, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, and New York, all of whom have some participating counties. None replied to a request for comment on whether they believe that their office has the authority to restrict 287(g) contracts and other ICE deals. “In New York, I think it’s the state legislature that’s best positioned to pass this kind of reform on a statewide level,” Zachary Ahmad, a policy counsel with the New York Civil Liberties Union, told me. A legislative proposal stalled in New York this year, as it did in most of these states; the Colorado governor even threatened to veto such legislation.

New Jersey could also strengthen Grewal’s policy by enshrining it into law. “We have to ensure that these policies are codified so that any other administration would have to uphold these policies,” Johanna Calle, director of the New Jersey Alliance for Immigrant Justice, told me.

The 287(g) program has gained steam under the Trump administration, but it has also faced organizing blowback. Three populous counties quit after ICE-friendly officials lost in 2018, and sheriff’s races in Louisiana and Virginia this fall could spark similar outcomes.

Two New Jersey counties, Cape May and Monmouth, were in the 287(g) program at the time of Grewal’s directive, which terminates these contracts effective today. (Salem County was also a member at the start of 2019 but its contract expired this summer. An earlier directive, issued by Grewal in 2018, had addled hurdles to the renewal process.)

The sheriffs of Cape May and Monmouth, who are both Republicans, remain defiant. They have threatened legal action and they argue that Grewal’s policy endangers public safety. “This sanctuary directive will make our communities less safe, since it places people in those communities at risk for increased violence,” said Monmouth County Sheriff Shaun Golden, who is running for reelection in November. (His Democratic challenger, Raymond Dothard, did not respond to a request for comment.)

Proponents of 287(g) cite stories of undocumented individuals who allegedly committed a crime to suggest that it poses public safety risks for local law enforcement to not partner with ICE. As of Thursday, the ICE web page devoted to 287(g) lists three examples of people who were issued an immigration detainer by local officers deputized under the program; this list includes two people from Monmouth and Cape May counties.

This tactic is a variation on the Willie Horton strategy of championing punitive policies through sensationalized anecdotes, often involving people of color. It is belied by a new study from the University of California, Davis, which found no connection between deportation and crime. In any case, it is misleading to bring up the dangerousness of not detaining someone on immigration grounds since public safety factors are baked into the bail and release decisions made by New Jersey courts in the course of an individual’s independent criminal proceedings, regardless of immigration status.

The tactic also exploits the false assumption that someone who is arrested must have committed a crime. While it is true that people checked by 287(g) officers have been arrested and brought to jail over some offense, they typically have not been convicted. A U.S. citizen would be released if their criminal charges were dropped, but the same may not be true for an undocumented immigrant living in a 287(g) county.

But Grewal himself used aspects of Golden’s rhetoric. In justifying the preservation of other forms of cooperation, a statement issued by the attorney general’s office hints at a link between ICE cooperation and public safety. “The Directive explicitly allows any state, county, or local law enforcement agency to refer any individual to ICE who has been charged with a ‘violent or serious offense,’” it states. “That is why ‘the vast majority of New Jersey’s 21 counties have already proven able to protect public safety without entering into 287(g) agreements of their own.’”

In an earlier directive, issued in 2018, Grewal restricted but did not abolish circumstances under which local law enforcement can notify ICE or honor immigration detainers to “violent or serious offenses.”

Last week, the same directive that banned 287(g) also expanded the definition of a “violent or serious offense.”

Involving ICE when someone is charged with a crime violates the presumption of innocence, Calle warned. They may be cleared or acquitted, but only after getting ensnared in immigration proceedings. And people who are convicted face a court-ordered sentence anyway. “The criminal justice system is broken,” Calle said. “ However, there is a criminal justice system. If someone commits a crime, they go through that process.”

Grewal’s office did not reply to a request for comment about adding immigration consequences to criminal proceedings, nor about the suggestion of a link between ICE cooperation and public safety.

Calle added that the court system is already tasked with making public safety assessments when deciding whether to release someone pretrial. “The assumption that an immigrant who commits a violent crime is somehow running loose in our communities isn’t real. We in the state of New Jersey decided that people that do not pose a public threat to our public safety are deemed to have been allowed to go back to their communities,” she said, referring to the state’s recent bail reform. “Then why are we going to be treating immigrant communities differently?”