Political Report

In Massachusetts, the Democratic Party Shifts Toward Supporting Voting Rights for All

Most members of the state’s congressional delegation now say they support restoring voting rights to incarcerated people. Will Tuesday’s primaries elect more proponents?

Most members of the state’s congressional delegation now say they support restoring voting rights for incarcerated people, a testament to organizing successes. Will Tuesday’s primaries elect more proponents?

Stephen Lynch was still a state senator in 2000 when he voted for the constitutional amendment that ended universal suffrage in Massachusetts. The measure was part of a backlash fueled by Republican Governor Paul Celluci against electoral organizing at the Norfolk prison in 1997.

Until then, Massachusetts didn’t practice felony disenfranchisement, just like Maine and Vermont, its New England neighbors. The 2000 amendment—championed by Celluci, passed by a Democratic legislature, and approved by voters in an era of tough-on-crime norms—stripped citizens incarcerated for a felony of the right to vote. Due to the measure, approximately 11,000 people were barred from voting in the state in the 2016 presidential election; these citizens were disproportionately African American.

Today, though, the call for universal suffrage has gained steam among Democratic officials in the state, fueled by years of activism by Massachusetts organizers working from both inside and outside prisons, and by the renewed national reckoning around racial injustice in the criminal legal system.

Heading into Tuesday’s primaries, The Appeal: Political Report has determined that a clear majority of the state’s all-Democratic congressional delegation—seven out of 11—has gone on the record in favor of abolishing disenfranchisement altogether.

And Lynch, now a U.S. representative, faces a challenge in Tuesday’s Democratic primary from Robbie Goldstein, a progressive who says he supports abolishing felony disenfranchisement.

Goldstein said Lynch’s 2000 vote is part of a pattern that shows “he has no intention of addressing the systemic racism that exists in our society, including in the criminal legal system.” Lynch’s campaign did not answer repeated requests for comment on his position.

“Prison disenfranchisement specifically impacts Black and brown communities that are targeted by current policing policy and the failed ‘war on drugs,’ limiting their abilities to make their voices heard in the political process,” Goldstein told me.

Many studies show that African Americans are more likely to be incarcerated when convicted of a crime, including when controlling for the underlying offense. In Massachusetts, that translates into an unequal loss of political power: 6 percent of the state’s adult population is Black, but that compares to 27 percent of those disenfranchised as of 2016, according to the Sentencing Project.

“If we as a nation are going to do the difficult work of addressing centuries of racism, we must be willing to have difficult conversations and acknowledge our prior mistakes and bad actions,” Goldstein said.

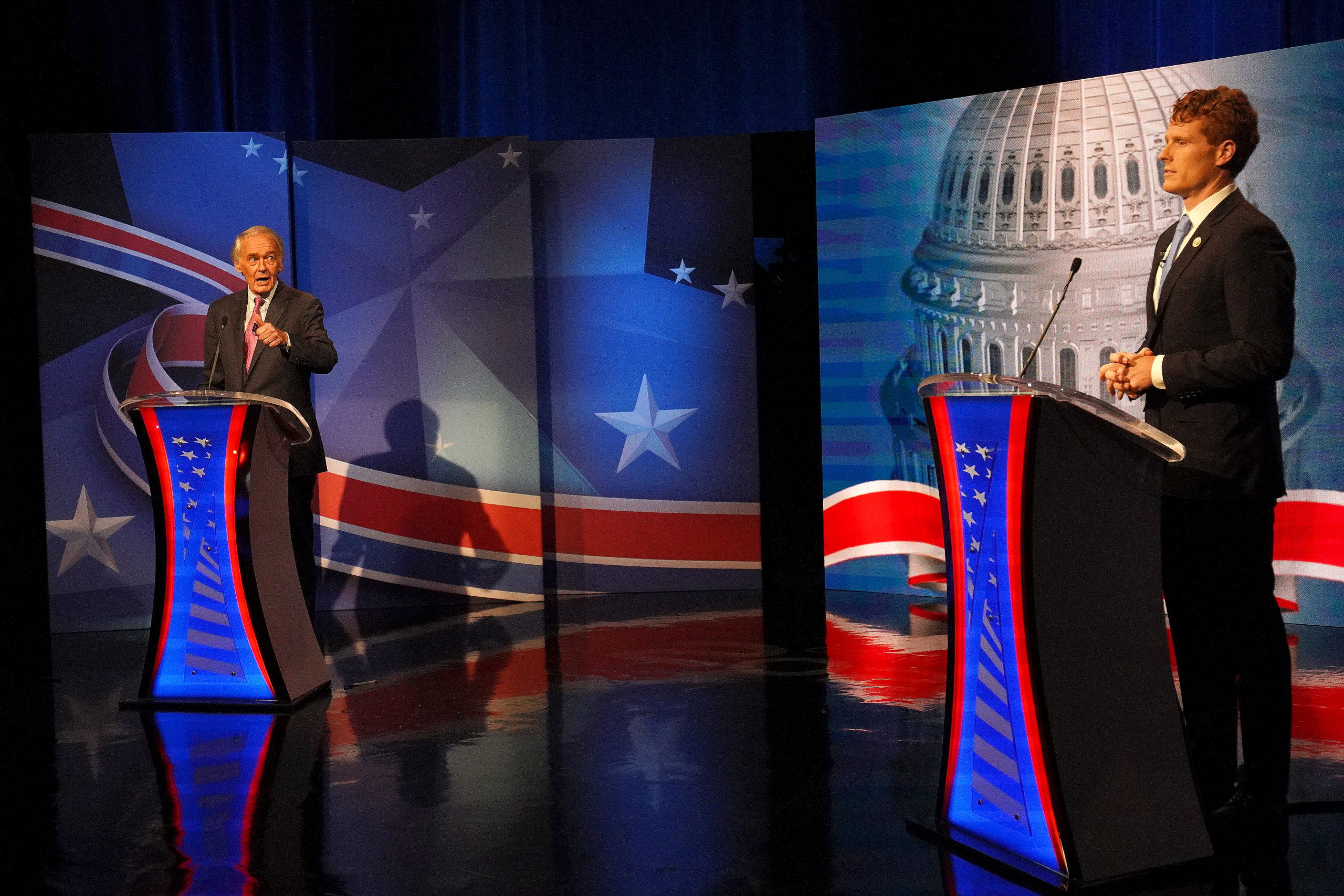

Goldstein’s challenge has not gained nearly as much attention as the other explosive Democratic primaries that are taking place on Tuesday. Media coverage has focused largely on the U.S. Senate race between incumbent Ed Markey and U.S. Representative Joe Kennedy and the U.S. House race between incumbent Richard Neal and Holyoke Mayor Alex Morse. All four told me via campaign spokespeople that they support extending the franchise to all voting-age citizens.

—

This is a significant turnaround from even just a year ago, when I was struggling to find public officials willing to discuss the issue.

And it reflects growing momentum for activists who have long made the case that the fight for voting rights and racial justice cannot stop at the doors of the prison.

The Emancipation Initiative, a Massachusetts-based organization, has championed the voting rights of incarcerated people for years, as the Political Report has covered. Working alongside other groups in the Mass POWER coalition, which includes Families for Justice as Healing and the National Council for Incarcarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls, organizers launched a petition drive to put the issue on the ballot last year, though that effort did not succeed.

Since 2016, they have also organized a project called #DonateYourVote, which pairs an incarcerated person and a free person who commits to voting according to their disenfranchised partner’s preferences.

Elected officials finally picked up the issue in 2019. State Senator Adam Hinds introduced a measure to extend the right to vote to all adult citizens, though it was shelved in committee on a secret vote that spring. And U.S. Representative Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts filed a congressional resolution that called for the same.

“Perhaps we would be further along in transforming the criminal legal system if people were held more accountable to those that are behind the walls,” Pressley told The Appeal at the time. (Her point mirrors a case that officials in Maine and Vermont are making as well.)

Since then, Pressley has gained congressional allies on this issue, and the state constitutional amendment has gained new proponents.

—

Markey and Kennedy are facing off in a bruising Senate battle. But on this issue, at least, they have staked the same position: Both wrote in questionnaires for Progressive Mass, an advocacy group, that they opposed prison disenfranchisement.

Their campaigns confirmed that position in exchanges with the Political Report. “Congressman Kennedy believes felony disenfranchisement should be abolished, and he supports federal and state-level efforts to reinstate voting rights for all formerly and currently incarcerated people,” said a spokesperson for Kennedy’s campaign.

“Senator Markey recognizes that felony disenfranchisement is intimately connected with efforts to criminalize being Black,” said a spokesperson for Markey’s campaign. “Empowering persons in prison to vote is critical to their reintegration into society and must be part of a broader push that emphasizes rehabilitation over punitive punishment.”

Markey’s spokesperson stated that the state legislature should take up and adopt a constitutional amendment, but she also added that this issue goes beyond people’s right to vote. It’s about the “dignity” and “voices” of incarcerated people, she said, and the sort of electoral organizing that occurred in the Norfolk prison in 1997 should be encouraged so that people speak up on matters on which they have “firsthand experience.”

The state’s other high-profile primary is in the First Congressional District between Neal, the incumbent, and Morse. Here, too, both sides now say they back abolishing disenfranchisement.

A spokesperson for Neal’s campaign told me that the incumbent wants the state legislature to adopt the constitutional amendment filed last year, and that he also backs Pressley’s proposal to bring this about via federal legislation. As chair of the Ways and Means Committee, Neal is one of the most powerful House Democrats to indicate support for this position.

Neal’s response came amid the biggest primary fight he has faced in decades, which makes it a barometer of sorts of how issues linked to voting rights and racial justice are playing out in the Democratic electorate.

Morse, who is backed by national progressive groups and by U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, had already said he favors ending prison disenfranchisement this winter, in his Progressive Mass questionnaire. Neal did not return that questionnaire at all.

“This shouldn’t be a radical idea,” Morse told me in a written statement when asked to elaborate on that position.

“Our criminal justice system today deliberately shuts people out of our political and civic life,” he said. “We have people in our jails who shouldn’t be there. And even those who have committed crimes should be given the chance to rehabilitate their lives. They’re still American citizens, and should be free to exercise their right to vote and to help shape the future of the country they call home.”

On the campaign trail, Morse has faulted Neal for voting in favor of the 1994 crime law, which encouraged states to impose tougher sentences, furthering the country’s ballooning incarceration rate and thus also increasing the number of people who are disenfranchised. Neal has replied that the law contained provisions like the Violence Against Women Act to justify his vote.

Over in the Sixth Congressional District, U.S. Representative Seth Moulton also indicated in his Progressive Mass questionnaire that he backs abolishing disenfranchisement and enabling “those currently incarcerated” to vote.

But his campaign did not respond to requests for comment about this questionnaire answer.

On Tuesday, Moulton faces primary challenger Angus McQuilken, who told Progressive Mass he opposes voting rights for incarcerated people.

Massachusetts’s Fourth Congressional District, finally, is the state’s only other contested federal primary, and it is the only one without an incumbent since Kennedy retired to run for Senate.

Seven Democrats are still running to replace Kennedy and the ratio in favor of expanding voting rights is even more lopsided. Six of the seven—Becky Grossman, Alan Khazei, Ihssane Leckey, Natalia Linos (whose responses are on her website), Jesse Mermel, and Ben Siegel—wrote in Progressive Mass questionnaires that they support extending voting rights to incarcerated people.

The only candidate who opposes this proposal, Jake Auchincloss, is a Newton city councilor who is perceived as a front-runner and who received the Boston Globe’s endorsement. Auchincloss has come under fire recently for past comments he made about the burning of the Quran.

I also reached out to the state’s five members of Congress who are not facing a primary this year, or else who are not on the ballot at all, to ask their latest position on this issue.

Representatives Katherine Clark and Jim McGovern support proposals to extend voting rights to incarcerated people, spokespeople from their respective offices said.

But the office of Senator Elizabeth Warren, who stated in 2019 that “we can have more conversation about” whether people should vote while incarcerated, did not clarify her stance on prison disenfranchisement. Nor did the offices of Representatives Bill Keating and Lori Trahan.

Keating was in the state legislature in 1998 when the amendment to disenfranchise incarcerated people came up to a vote for the first time. He voted in favor of the measure, according to copies of legislative archives shared by elly kalfus, a researcher and coordinator with the Emancipation Initiative. Keating became district attorney of Norfolk County in 1999; the measure he backed gave him new authority to shape whether people would retain the vote through his prosecutorial discretion.

—

Even as the tide shifts in Massachusetts, the state is falling behind the change bubbling up elsewhere. In a historic milestone, adopted in an emergency response to Black Lives Matter protests, Washington D.C. abolished felony disenfranchisement in July.

And progressives are winning elsewhere on a platform of voting rights for all adult citizens. Those include Jamaal Bowman, a progressive who defeated a U.S. House incumbent in New York in June, and prosecutorial candidates in Austin, Texas, and Portland, Oregon. Within Massachusetts, Boston’s DA has also signaled support for this position.

Still, support for abolishing disenfranchisement is by no means broadly held among national Democratic politicians. Neither Joe Biden nor Kamala Harris, the party’s presidential ticket, support extending voting rights to people in prison. A bill adopted by the U.S. House last year would enfranchise people upon their release from prison. Although it leaves out those who are incarcerated, that change would by itself tremendously expand voting rights in the 32 states that, unlike Massachusetts, still disenfranchise many people who are not in prison.

Goldstein thinks that the “urgency of the Black Lives Matter movement and systemic racism” may continue pushing more Democrats toward universal suffrage. “To fight injustice, those most impacted must be able to use their voice at the ballot box,” he said.