Political Report

In 2020, Look at Sheriffs and Prosecutors Too

In Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, and beyond, next year will bring blockbuster local elections that could overhaul law enforcement and criminal justice.

In Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, Phoenix, and beyond, next year features blockbuster local elections that could overhaul law enforcement and criminal justice. Some candidates are proposing bolder reforms.

Explore our 2020 portal for coverage of specific states and elections.

Next year is headlined by the re-election bid of a president whose administration keeps launching assaults against progressive prosecutors and sheriffs.

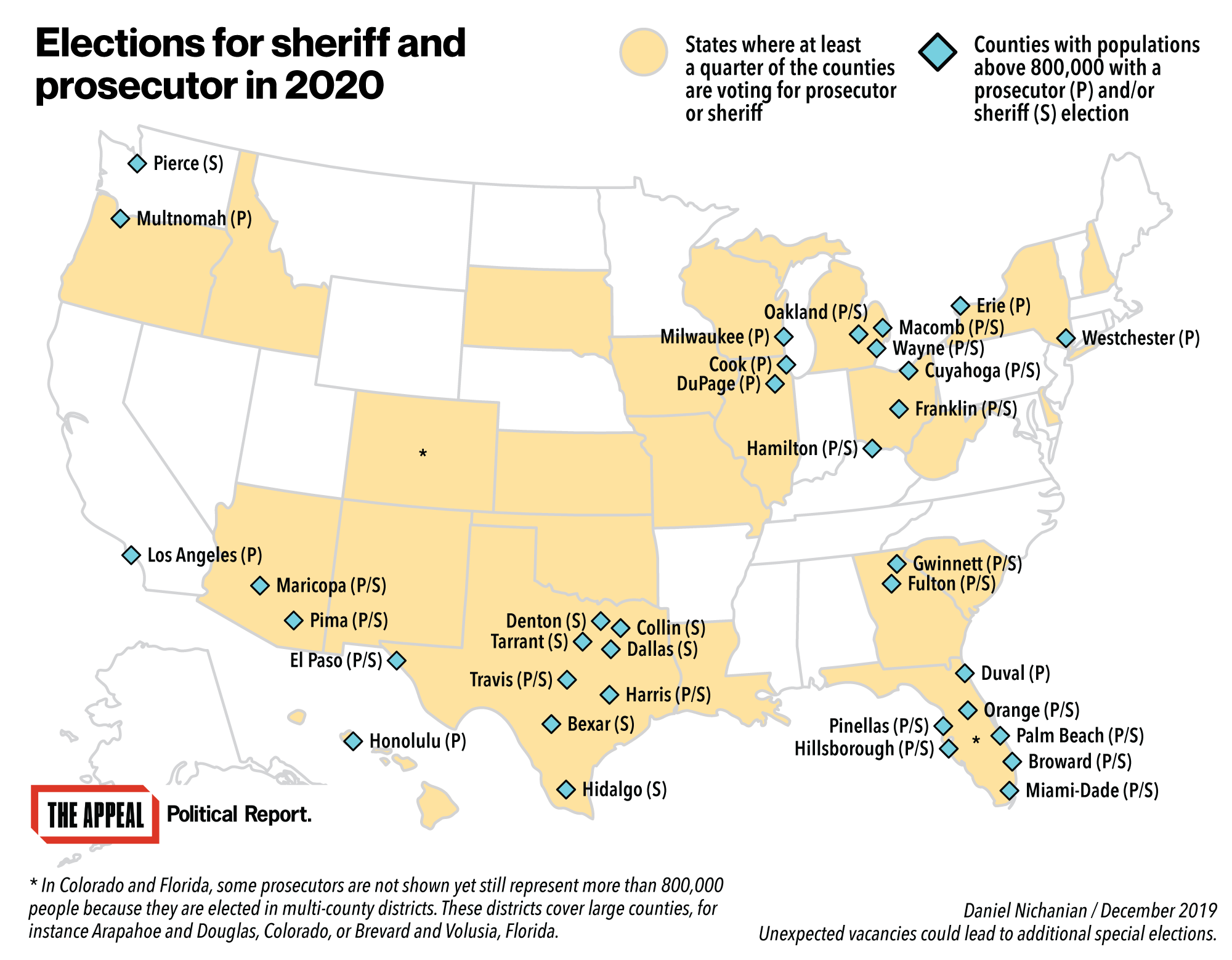

But President Trump’s fate won’t be the only test of what voters think of these assaults. Many of the nation’s most populous counties will hold high-stakes elections that will decide how much they overhaul their criminal legal systems in the years ahead. This includes Los Angeles, Cook (Chicago), Harris (Houston), Maricopa (Phoenix), Miami-Dade, and Tarrant (Fort Worth).

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Approximately 2,300 prosecutors and sheriffs will be elected across the country, according to the Political Report’s new master list of 2020 elections.

These elections represent opportunities for the reform movement to replicate its recent successes. Criminal justice and immigration activists have upended expectations of who can win races for prosecutor or sheriff. They have helped oust incumbents with punitive records; made even punitive prosecutors want to adopt some reform rhetoric; and fueled wins for candidates who favor significant cuts to incarceration and criminalization. And in 2019, their success broke out of big cities and into suburban and rural jurisdictions.

Will those trends continue in 2020? The answer is sure to have profound policy implications. Candidates have already clashed over bail reform in Houston, cooperation with ICE in Fort Worth, the death penalty in Los Angeles, and jail conditions in Phoenix, where former Sheriff Joe Arpaio is mounting a comeback.

But 2019 was also a reminder that the movement has plenty more to surmount. In state after state, most prosecutorial elections drew just one candidate. Others attracted no one who focused on criminal justice reform; elsewhere, candidates who talked of these issues were snubbed by their own party.

Among candidates who have won on progressive platforms, many remain cautious when it comes to policies that would actually reduce their powers and shrink the criminal legal system, rather than modify the ways its coercive force is deployed. There are signs that some candidates are proposing bolder reforms, though, for instance by clarifying areas DAs should not be involved. And with a number of incumbents elected as progressives running for re-election next year, 2020 will provide an opportunity to take stock of how transformative this wave of reform officials has really been.

Below is a preliminary preview of some of the year’s likely battlegrounds.

In the nation’s four biggest counties, incumbent prosecutors with varying records seek re-election: If you thought Queens or San Francisco were major prizes this year, wait until 2020. Four counties that are each more populous than 24 states elect their prosecutors.

In Los Angeles County, home to more than 10 million people, District Attorney Jackie Lacey has drawn criticism for failing to implement necessary reforms and perpetuating discriminatory practices, and her re-election bid is already spilling national ink because of George Gascón’s decision to resign as San Francisco DA to challenge Lacey. Both are Democrats. “We have been doing things for the past 40 years that are not only inhumane but expensive and also has not made us any safer,” he said. At least three other candidates are also running, including one—Rachel Rossi—whose background is in public defense rather than prosecution.

In Cook County (Chicago), State’s Attorney Kim Foxx is running for re-election, four years after grassroots organizing against her predecessor Anita Alvarez fueled her win. Foxx, a Democrat, has rolled out reforms meant to increase diversion and transparency; jail and prison sentences fell by 20 percent in 2018. Five candidates have filed to run against Foxx, including a number of former prosecutors; for now, opposition has come from people skeptical of reform and of her handling of the Jussie Smollett case, rather than from her left.

Kim Ogg, the DA of Harris County (Houston), is seeking a second term; she clashed with reform advocates this year for opposing bail reform, requesting to hire more than 100 new prosecutors, and trying to execute an intellectually disabled man. In Maricopa County (Phoenix), newly appointed prosecutor Allister Adel, who has aligned herself with her reform-skeptic predecessor, faces voters for the first time. Ogg and Adel have drawn multiple reform-minded challengers.

If 2019 broadened the geographic breadth of decarceration, 2020 could accelerate that trend: Under next year’s marquee elections are dozens of prosecutorial races in counties that epitomize the role that DAs have played in pursuing punitive policies, or in not holding law enforcement officers accountable.

In Miami-Dade, Katherine Fernandez Rundle is seeking re-election three years after deciding to not charge prison guards who threw a man into a boiling shower until he died; she has since repeatedly drawn attention for decisions to not press charges against police officers, including over alleged brutality. George Brauchler, the DA of Colorado’s Arapahoe and Douglas counties, is an avid death penalty proponent who has fought efforts to review juvenile life-without-parole sentences, as has Jessica Cooper in Oakland County (Michigan). Travis County (Austin) DA Margaret Moore is accused of mishandling the prosecution of sex crimes. In Cuyahoga County (Cleveland), prosecutor Michael O’Malley is facing demands that he curb the use of cash bail. In Louisiana, Orleans Parish DA Leon Cannizzaro has ramped up more aggressive prosecutorial practices toward minors, while Calcasieu Parish John DeRosier reportedly solicits gifts as a condition for diversion.

And all prosecutors are on the ballot in Illinois, Ohio, and Wisconsin, three states that are responding aggressively to the opioid crisis by treating many overdoses as homicides.

Next year will be a referendum on these counties’ largely punitive status quo. The same is true in the races without incumbents in Florida’s Broward County, and in Honolulu.

Elsewhere, though, 2020 will be a referendum on prosecutorial reforms that have drawn resistance from other political officials.

St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner has fought with the local police union and was stymied by a local judge in her efforts to issue an exoneration. And in Orlando, Aramis Ayala, one of the most emblematic progressives elected in 2016, is not even seeking a second term in 2020 due to backlash against her opposition to the death penalty.

Other large counties, or counties where reform debates are already front-and-center, include Pima County, Arizona; Fulton (Atlanta) and Athens counties in Georgia; Lake County and Peoria County, Illinois; Washtenaw (Ann Arbor) and Wayne (Detroit) counties in Michigan; Hamilton County (Cincinnati), Ohio; Multnomah County (Portland), Oregon; and others.

But will anyone even run? Local elections are still frequently uncontested, even as their visibility grows. We’re likely to see more of the same during the 2020 elections.

In DuPage County, Illinois’s second largest, not a single major-party candidate filed against State’s Attorney Bob Berlin by Monday’s deadline. (Independents can still enter through June.) Berlin, a Republican in a blue-leaning suburban county, has fought criminal justice reforms.

Illinois has an early filing deadline—but this pattern may well recur across the country, as it did in 2019. This a major obstacle to those who push for reform or accountability through the polls.

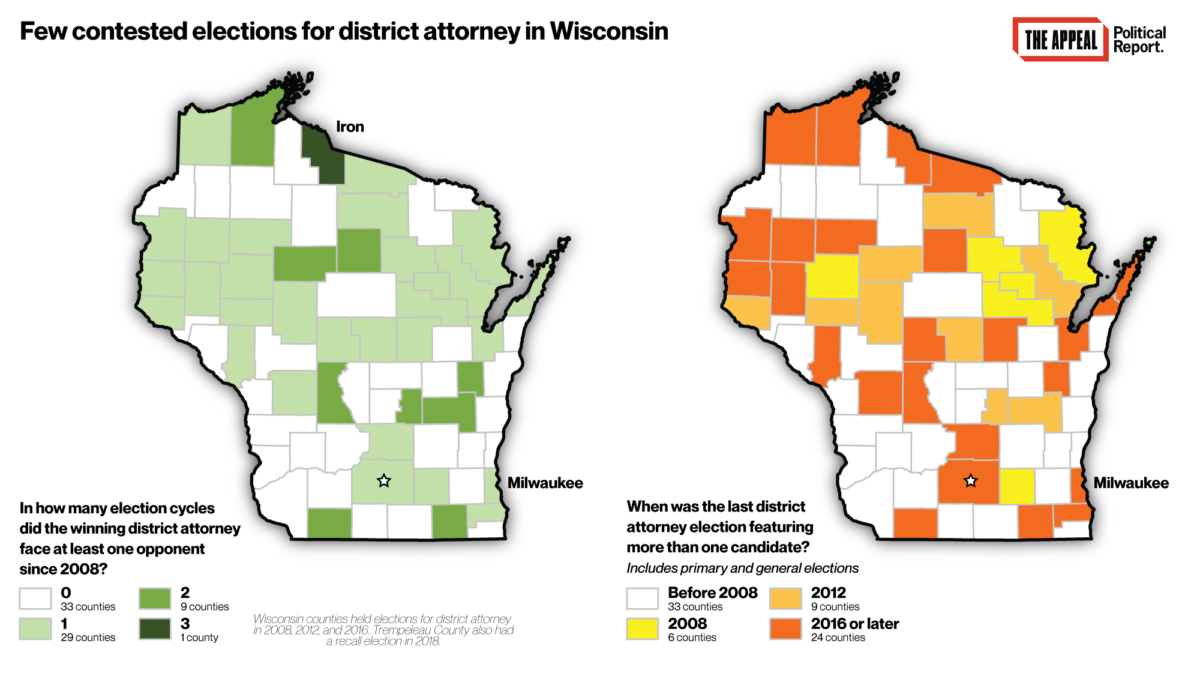

Take Wisconsin, which is electing its 71 DAs in 2020. A Political Report analysis found last year that most Wisconsin counties haven’t held a single contested election this entire decade. In fact, six of the state’s ten largest counties haven’t held a single contested election since at least 2008. “Let’s change this in 2020,” Ben Wickler, the chairman of the state Democratic Party, tweeted in October in response to this analysis. We will know after the June filing deadline whether the state has defied this historic dearth of competitiveness.

Will 2020 bring more pushback against DA associations that fight reforms? A slate of progressives ran (and won) on talk of coalescing against Virginia’s prosecutorial association, which has promoted punitive policies. Next year carries similar stakes in Arizona and Hawaii: Prosecutors successfully blocked reforms in both states this year, so the election of officials with different views could trigger a statewide realignment. Another test is in New York: Albany County DA David Soares, a Democrat, oversaw an offensive against the proposed pretrial reforms this spring when he was president of the District Attorneys Association of New York.

Policing and jail conditions are under the spotlight in sheriff’s elections: Joe Arpaio, the longtime GOP sheriff of Maricopa County, wants his old job back. He is running against Paul Penzone, the Democrat who beat him in 2016. As sheriff, Arpaio detained people in horrid conditions that were continually denounced for human rights abuses, operated in a facility (Tent City) he himself called a “concentration camp,” and oversaw a string of gruesome jail deaths. And he conducted street patrols that courts and government reports found amounted to systematic racial profiling.

But Arpaio’s record is only a window into the tremendous power sheriffs have over detention conditions and policing practices.

When he announced his challenge to Sheriff John Mina in Florida’s Orange County (Orlando), public defender Andrew Darling argued for supplementing attention to prosecutors with demands toward sheriffs.

“We often talk about a lot of young, progressive people running for State Attorney. But we don’t talk about that the criminal justice system actually starts before that,” he said. (Mina and Darling are both Democrats.)

Many officials whose records on policing and jails conditions have drawn criticism will be on the 2020 ballot. For example, last year in Florida’s Pinellas County, Sheriff Bob Gualtieri, a Republican, cited the state’s Stand Your Ground law when he declined to arrest a white man who shot an African American. And jail deaths ought to be a major issue throughout Georgia. The Appeal reported on dismal conditions in jails run by Fulton County (Atlanta) Sheriff Theodore Jackson and DeKalb County Sheriff Jeffrey Mann; both are Democrats who are up for re-election in 2020.

Where will ICE be a defining issue? Sheriffs play a huge role in expanding or restricting ICE’s power, so immigration policy could be on the line in dozens of counties with sheriff’s races this year. In particular, sheriffs typically control whether their county joins ICE’s prized 287(g) program, which deputizes sheriffs’ deputies to act like immigration agents within jails.

Over 50 counties in the 287(g) program as of this week also vote for their sheriff in 2020. The vast majority lean Republican, so they may be challenging for candidates who favor restricting ICE’s powers. But seven pop out as potential battlegrounds. Three voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016: Charleston (South Carolina), and Cobb and Gwinnett (Georgia). Four other counties narrowly voted for Trump in 2016 before voting for a Democratic Senate candidate in 2018: Nueces, Tarrant, and Williamson (Texas), and Pinellas (Florida). Bill Waybourn of Tarrant County (Fort Worth), for instance, has closely aligned himself with White House rhetoric and practices.

These seven counties combined have about six million residents. If some candidates who oppose 287(g) win in 2020, it would significantly shrink ICE’s reach in populous counties.

ICE could also be at issue in many other counties with 2020 elections: Sheriffs cooperate in many other ways, such as voluntarily agreeing to detain people based on ICE requests. Those include Democratic sheriffs like Jim Neil of Hamilton County (Cincinnati), Ohio.

Will officials do more to shrink the criminal legal system? Many reforms keep the criminal legal system as a central player, even as they steer resources to new programs. Some advocates are calling for much bolder moves like questioning whether law enforcement responses are necessary and targeting public authorities’ use of criminal justice as a solution to all sorts of social issues.

“The best thing prosecutors can do for people who need services is get out of the way,” a group of abolitionist organization states in a new document. They warn of “institutions that use threat of punishment to force treatment or coerce services,” and call on prosecutors to “advocate for resources to be distributed to community organizations that already provide services and for policies that redistribute resources.”

Boston DA Rachael Rollins drew startled reactions in 2018 when she ran on committing to simply not prosecute certain categories of offenses, rather than prosecuting them differently, or steering them toward still-coercive diversion program. But by 2019, decriminalization was a more expected part of the repertoire of the bolder progressives like Chesa Boudin in San Francisco and Tiffany Cabán in Queens. And 2020 already features conversations along those lines: Joe Kimok (in Broward County, Florida) would not prosecute sex work, and José Garza (in Travis County, Texas) would decline cases involving sale or possession of under one gram of any narcotics; few prosecutors until now have talked of declining drug cases other than marijuana.

In Houston, finally, it is the very size of a DA’s budget, rather than where the money is spent, that has become an electoral issue. Challengers Audia Jones and Carvana Cloud have both criticized the budget and staff increase requested by Ogg, the incumbent. Carvana Cloud told The Appeal this week that “more prosecutors means more prosecution. I don’t care how you spin it.” The money should be spent “to invest in education, healthcare, and housing,” Jones has said.