Political Report

Why ICE Cooperation Is Dangerous Even with Biden in the White House

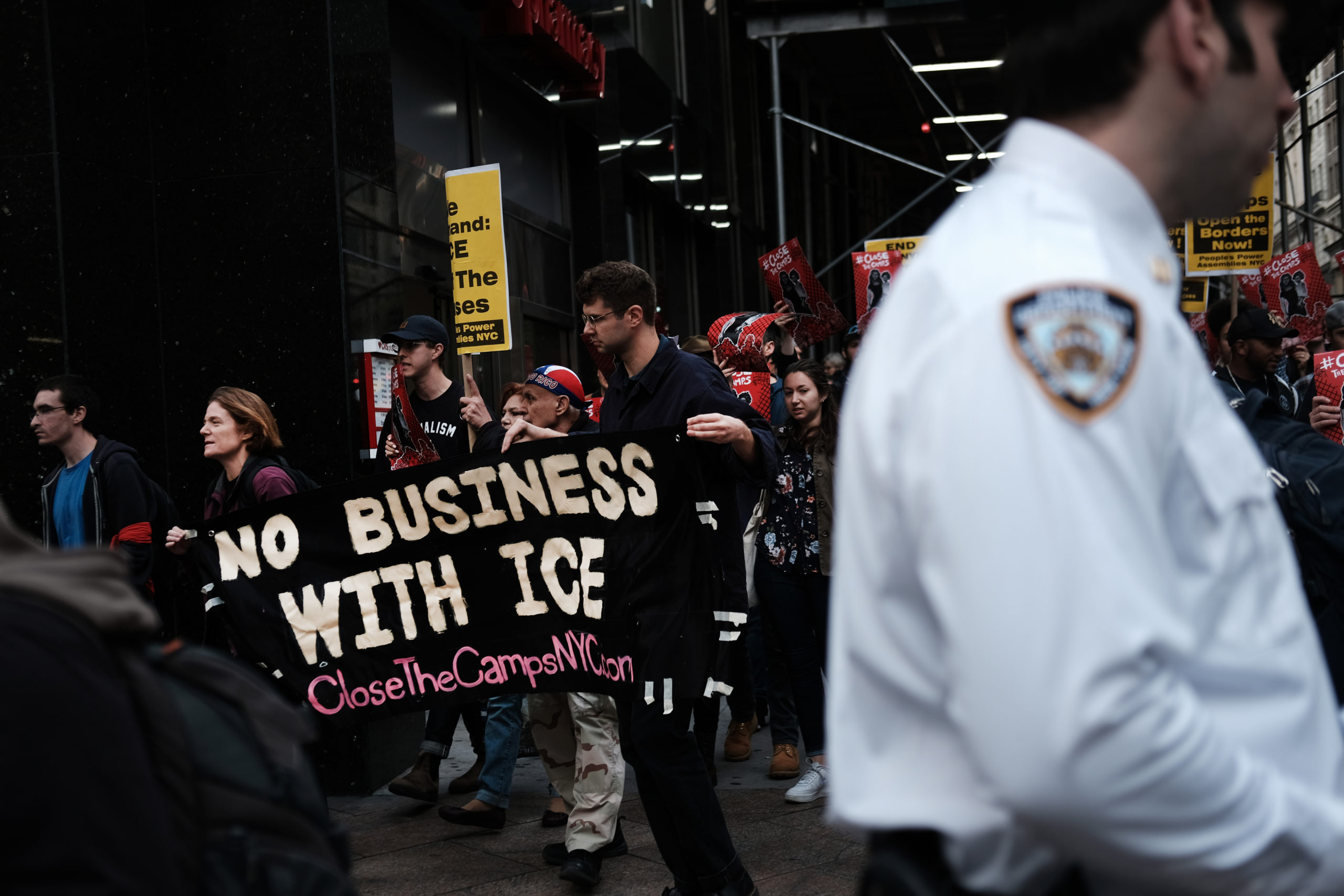

More public officials are breaking ties with ICE, as immigrants’ rights advocates double down on their case that local governments should avoid immigration enforcement regardless of Biden’s new policies.

More public officials are breaking ties with ICE, as immigrants’ rights advocates double down on their case that local governments should avoid immigration enforcement regardless of Biden’s new policies.

In the heightened atmosphere of former President Donald Trump’s administration, energized pro-immigration activism pressured many local officials to pull back from working with ICE and with Customs and Border Protection. Their successes helped hinder Trump’s drive for deportations, since internal immigration enforcement in the United States really functions through localities. It is local law enforcement that feeds ICE the data it needs to find and detain people, sheriffs who often hold detainees in their jails, cities and counties that decide when to coordinate with ICE.

Now President Biden has signaled an intent to undo Trump’s immigration legacy. The route so far has been somewhat lethargic and plagued by a disorganized approach to the border, but Biden has used his executive power to shift who will be targeted for deportation. Trump effectively made everyone without legal status an equal priority for deportation, a policy that led to the arrest of many longtime residents that the agency saw as easy pickings. Biden has reinstated more prioritization, instructing ICE to redirect its attention to people who have arrived recently as well as some people with criminal convictions.

But his new guidelines are a far cry from the freeze or end of detentions and deportations that many activists are demanding. Even if his plan was respected by ICE agents, it doubles down on connecting immigration enforcement to a criminal legal system rife with profiling. This has compounded the scrutiny on how, and whether, local officials will cooperate with ICE.

Eli Savit, the recently elected prosecutor of Michigan’s Washtenaw County (Ann Arbor), told The Appeal: Political Report that it would be “pretty cold comfort” for wary community members if he were to say, “Well, we’ll work with ICE and cooperate with federal immigration enforcement if we like the president.’”

Savit announced in February that he would bar information-sharing between his office and ICE, and help people obtain special visas reserved for trafficking victims and those who assist in the investigation of crimes. Other officials around the country have also forged ahead on sanctuary policies and curtailing their involvement with immigration enforcement.

Still, immigrants’ rights activists see new dangers on the horizon. Now that ICE is under the purview of a president who has repudiated his predecessor’s xenophobia and seems to be taking steps to ensure that a narrower group of people are targeted, some local officials may treat these changes as license to step away from earlier commitments. And this is driving activists to explain why the shifts underway are not enough and to press forward with their case against establishing or resuming cooperation with ICE.

In New Jersey, which has seen hunger strikes and vocal activism, local Democratic policymakers backtracked on their willingness to end ICE contracts in December, pointing to Biden’s arrival, and alarmed activists are now raising concerns that the legislature is wavering on whether to block counties from providing detention space to ICE.

Rosa Santana, who was a program director at the immigrants’ rights advocacy group First Friends of NJ & NY and now works at the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund, says numerous officials have told her that they are now more comfortable with immigration enforcement since it is more focused on people with a criminal record.

“You need to stop that narrative,” Santana said she told them. “It doesn’t matter if someone has had a past criminal conviction. They’re not [in detention] because of a past conviction. They’re there because of their immigration status.” (Immigration detentions are a civil, not criminal, matter. People are being held, often in private facilities with poor conditions, on top of any detention they may have also served because of a criminal arrest, and without the protections afforded to criminal defendants.)

Advocates also stress that ICE often ignores purported priorities, exploits what might seem like limited carve-outs, and can make even minor interactions with the criminal legal system snowball into deportation proceedings.

“What ICE represents doesn’t change because there’s a Democrat in office,” Katy Sastre of the New Jersey Alliance for Immigrant Justice told the Political Report in December. “They represent family separation.”

—

The administration’s shift in objectives was set off by an executive order that Biden signed on his first day in office. It is outlined in a memo issued by acting ICE director Tae Johnson, which redefines who will be targeted for most standard activities undertaken by ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations, including decisions linked to immigration detention and requests for local law enforcement.

The memo names three categories of people presumed to be priorities for enforcement: national security risks, such as people suspected of terrorism or espionage; people who attempted to enter or arrived in the country on or after Nov. 1, 2020; and people who are considered “a threat to public safety” because they are convicted of certain crimes or involved in gang activity. This last category is the most open to interpretation. But the guidelines don’t preclude the agency from arresting and deporting anyone else without legal status.

Biden’s directives are, broadly speaking, a return to the instructions outlined late in Obama’s first term by the so-called Morton memo. That memo narrowed immigration enforcement, and in that sense it was a victory for activists who gave Obama the moniker “deporter in chief” early in his tenure. But its implementation left a lot to be desired. Chicago Alderperson Carlos Ramírez-Rosa told the Political Report that he recalls going to the local ICE field office after the memo went into effect to assist constituents who had open deportation cases and should have been protected under the new criteria, yet ICE agents rejected many of their claims.

ICE typically isn’t strict about following federal directives, and there is limited oversight and a limited set of tools that could force the agency to actually comply.

Ellen Pachnanda, supervising attorney of the New York Immigrant Family Unity Project, worries that history is repeating itself, amid broader signs that ICE agents do not feel bound by Biden’s directives. Her organization has been trying to get people who don’t fit into the prioritized tiers released from detention, to no avail. “ICE retains a great deal of discretion to enforce the immigration laws as they see fit, and not necessarily follow the enforcement priorities,” she said. The agency has its own defiant internal culture and each field office operates a bit like its own fiefdom, and the extent to which each one complies will probably vary.

But even if they were followed to the letter, the administration’s instructions would not narrow the threat of deportation nearly as much as people may think.

Johnson’s memo, for example, directs ICE to prioritize people convicted of “aggravated felonies,” as defined in the immigration statutes. Despite the foreboding name, an aggravated felony does not have to be a felony nor an aggravated offense. It can include lower-level behaviors like perjury and theft—if the punishment imposed is at least one year in prison—and filing a false tax return. Advocates have similarly decried the fact that the Dream and Promise Act passed by the House last week, which is seen as a general road map for congressional Democrats’ priorities, contains a number of carve-outs that would bar people with criminal contact from access to its relief provisions.

“People try to separate criminal justice reform and immigration reform, but it’s a never ending-cycle,” said Pachnanda. “The very communities that are targets of the police, and have been, the Black and Latinx communities, now are going to be left out of immigration reform because of these old convictions.”

These issues have raised concerns that Biden’s team has not seriously grappled with the ways a racist criminal legal system intersects with immigration enforcement.

Even routine contact with law enforcement, to which people of color are far more likely to be subjected, can be the spark that leads to deportation by putting people on ICE’s radar through automatic criminal justice data-sharing. Local law enforcement can not only be the spark but the reagent when, for example, sheriffs and other jail wardens choose to do ICE’s bidding and help actively identify and detain people who may have violated immigration law.

ICE can make custody determinations pretty much any way it sees fit, and seek to keep people behind bars based on its own assessments of their dangerousness. Even if someone is initially arrested on criminal grounds, they can be kept in detention on civil grounds if ICE requests it even after charges are dropped and even after they have completed their sentence.

Since November, a slate of new sheriffs who won with the support of immigrants’ rights groups have ended their offices’ long-standing policies to detain people for ICE. One of them is Kristin Graziano in Charleston County, South Carolina. She says she would not be allowed to tell a judge, “I think this guy’s really dangerous, and I know he’s already served his time … but I think [he] needs to stay in jail.” She added, referring to ICE, “we can’t do it, and neither should they.”

Graziano told the Political Report that ICE tried to strong-arm her into continuing to cooperate with the agency after she became sheriff. “They came to meet with me and to congratulate me, and to ask to work together, but in the same sentence threatened to ramp up enforcement in my community if I didn’t do what they wanted,” she said. ICE’s public affairs office did not reply to a request for comment on her statement.

Instead Graziano announced in January that she was ending an agreement to detain immigrants and pulling Charleston out of ICE’s 287(g) program, which gives sheriff’s deputies the authority to run immigration checks in jails and hold people on suspected immigration violations. Graziano has doubled down on her decision since Biden entered the White House, defending it in the Post and Courier this month.

Other local officials are also taking steps to protect people from immigration enforcement. Savit, the Ann Arbor prosecutor, asked his staff in February to take the collateral consequences of convictions into account when they prosecute cases. He also plans to prosecute fewer lower-level offenses in the first place. “I don’t see much use in sending a 19-year-old back to a country that they do not know because they were caught with a small amount of drugs, which is something that, for a citizen like me, wouldn’t even carry jail time and I’d be allowed to move on with my life,” he told the Political Report.

Ramírez-Rosa, the Chicago alderperson, fought to stop public authorities in the city from being allowed to share information about people who were in the city’s gang database with ICE, alongside other loopholes. People may see that to be a small, targeted exception, but the city’s gang database is a notoriously flawed and expansive mechanism that ultimately stripped immigrants of their sanctuary protections based on evidence as shoddy as wearing the wrong clothing.

Ramírez-Rosa says his objective was to communicate to undocumented and mixed-status households that “in no case, no exceptions, could their interaction with the Chicago Police Department, or with city officials, result in the local police or city officials turning them over to ICE.”

ICE and its allies assert that cooperation between their agents and local law enforcement enhance public safety, but immigrants’ rights activists point out that it leads the immigrant community to be reticent to interact with local law enforcement and even emergency services and other public or municipal agencies. Vulnerable immigrants and their families are often not in a position to parse the particularities of their jurisdiction’s cooperation guidelines to determine their level of relative safety; any cooperation at all sends the simple message that their local officials are working with ICE.

When public officials in sanctuary jurisdictions leave carve-outs in non-cooperation policies, there are slip-ups, and those cannot be undone. ICE will file removal proceedings no matter how someone came to their attention, such as the case of a man turned over to ICE in New York City based on an acknowledged “operational error.”

“The mistakes lead to removal, they lead to death, they lead to the destruction of families,” said Pachnanda, the New York Immigrant Family Unity Project attorney.

Those who vow to continue resisting ICE say this is about their community’s needs, not about whoever is occupying the White House. “Even when you’re able to win those changes at the federal level,” said Ramírez-Rosa, “it can be very tentative because a new president like Trump would come along and undo all of that.”

Asked if the change in administrations had factored into her decision to pull out of ICE’s 287(g) program, Graziano said, “I could care less about national politics, and quite honestly I’m fed up with all of it. Change happens at the local level.”