Political Report

Cambridge Asserts Community Control over Surveillance Technology

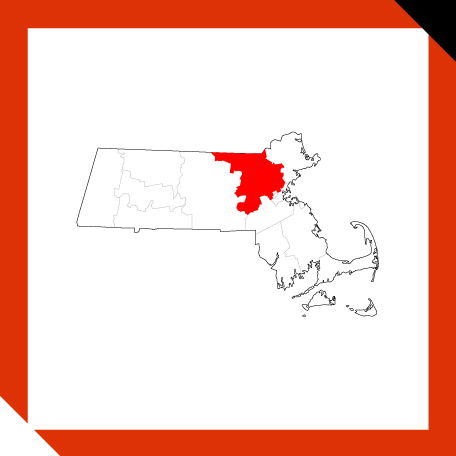

Cambridge, Mass., joined a small number of jurisdictions around the country that mandate transparency and community control over the use of surveillance technology.

Last week, the Daily Appeal looked at the NYPD’s launch of a drone program and the civil liberties concerns it raises, given the department’s history of unlawful surveillance, including of mosques and Muslim New Yorkers. The nation’s two largest police departments, the NYPD and the LAPD, now both have drone programs. The NYPD sought input from the New York Civil Liberties Union and the City Council on its drone policy before the official start of the program and describes the drones as intended primarily for non-surveillance purposes. But much of NYCLU’s feedback was ignored, according to the organization, and the final policy has loopholes that give enormous leeway for surveillance.

Last week, the Daily Appeal looked at the NYPD’s launch of a drone program and the civil liberties concerns it raises, given the department’s history of unlawful surveillance, including of mosques and Muslim New Yorkers. The nation’s two largest police departments, the NYPD and the LAPD, now both have drone programs. The NYPD sought input from the New York Civil Liberties Union and the City Council on its drone policy before the official start of the program and describes the drones as intended primarily for non-surveillance purposes. But much of NYCLU’s feedback was ignored, according to the organization, and the final policy has loopholes that give enormous leeway for surveillance.

Elsewhere, there is momentum toward greater community control and oversight. Last Monday, Cambridge, Massachusetts, joined a small number of jurisdictions around the country that mandate transparency and community control over the use of surveillance technology. The City Council passed an ordinance that requires the body’s approval before any surveillance technologies can be “funded, acquired, or used.” The ordinance came out of two years of community input and negotiations over the language of the law and was backed by the city’s police commissioner.

The ordinance covers a wide range of devices and software including “automatic license plate readers, video surveillance, biometric surveillance technology including facial and voice recognition software and databases, social media monitoring software, police body-worn cameras, predictive policing software.” The law also covers surveillance technology that is already in the city’s hands. The police or any other city department seeking to use the technology must provide the City Council with information including the technology’s capabilities, the precise intended use, how the data would be preserved and protected, the cost of acquiring and using it, and the potential negative effects on civil rights and civil liberties and how they would be prevented. Under the law, city departments, including the police, must regularly report how they are using the surveillance tools.

Cambridge became the first Boston-area town to have legislation regulating the acquisition and use of surveillance equipment. The City Council of Lawrence, Massachusetts, passed a similar ordinance in September and the ACLU of Massachusetts is pushing for the adoption of legislation in two other towns, Brookline and Worcester.

Laws of the type passed by Cambridge’s City Council were first passed in Santa Clara County in California in 2016. Seattle; Davis, California; and other cities soon followed. This year, Oakland, California, passed an enhanced version of the law.

Oakland’s ordinance raised the bar in two crucial ways. The first was that it clearly defined surveillance technology to include software used for surveillance-based analysis. The second was that it prohibits city agencies from entering into nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) or contracts that undermine the protections of the ordinance. The Electronic Frontier Foundation highlighted the importance of these provisions, noting that, “For years courts and communities have been kept in the dark about the use of surveillance technology as a result of NDAs not only with tech vendors but also with federal agencies including the FBI.”

The NYPD is among those agencies that have defended the use of nondisclosure agreements—and resisted community oversight of surveillance technologies. In City Council hearings last year on the Police Oversight and Surveillance Transparency (POST) Act, a deputy NYPD commissioner explained the department’s failure to make contracts available for review, saying, “Many of these technologies, because they’re only effective if bad people don’t know how they work and how to defeat it, are given to us pursuant to very strict nondisclosure agreements.” The range of surveillance practices that the NYPD fails to disclose information about includes facial recognition software, predictive policing software, X-ray vans, the “mosque raking” program that targeted the city’s Muslim communities, and body-worn cameras, according to reporting by the Intercept.

Like the ordinance adopted the Cambridge City Council, the POST Act would require the NYPD to report and evaluate all surveillance technologies that they intend to acquire or use. However, Electronic Frontier Foundation notes the limitations of the POST Act, which, unlike the ordinances adopted in Berkeley, Oakland, Seattle, Nashville, and now Cambridge, would not give the New York City Council veto power over the acquisition of surveillance technology. Nor would it give the City Council the power to order the NYPD to cease use of equipment that it used in violation of the published policy.

Concerns about surveillance technology in Cambridge go back to at least 2009 when the Department of Homeland Security installed eight cameras on city streets—a small fraction of the more than 100 installed in the greater Boston area. Going under the gaze of video cameras is the cost of being in public in most large cities, but in Cambridge, thanks to public outcry, the cameras were never turned on. And thanks to the recent ordinance, they still cannot be turned on without approval from City Council.

First published on Dec. 17, 2018 in the Daily Appeal newsletter