Political Report

Brian Kemp’s Sham Democracy in Georgia

The poster boy of Republican voter suppression is using loopholes in state law to cancel key Supreme Court and district attorney races in 2020.

The poster boy of Republican voter suppression is using loopholes in state law to cancel key Supreme Court and district attorney races in 2020.

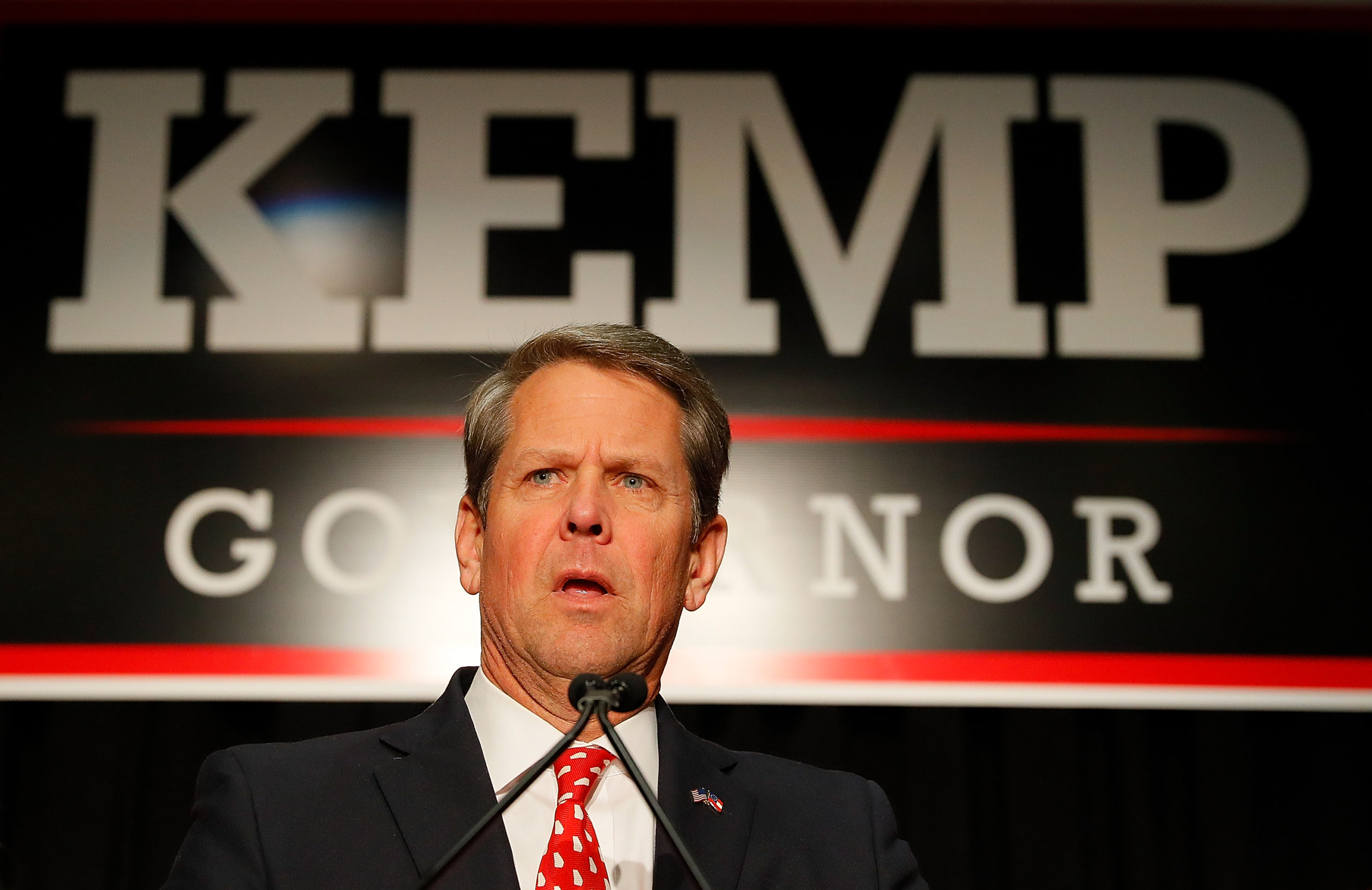

Brian Kemp rose to national prominence in 2018 after eking out a narrow victory in Georgia’s gubernatorial race, in which he deftly leveraged his position as Georgia’s secretary of state—the person responsible for administering elections—in order to win the promotion he coveted.

As Democrat Stacey Abrams vied to become America’s first Black woman governor, his office froze the voter registration applications of more than 50,000 Georgians, nearly 70 percent of whom were Black. It purged 1.4 million voters from the rolls between 2012 and 2018, and stood by as county officials closed hundreds of polling places, many of which were located in low-income and minority communities.

Two days before in-person voting began, Kemp even accused Democrats of “hacking” the state’s voter database in an announcement on the secretary of state’s website; 16 months later, the Georgia attorney general’s office closed its investigation of the governor’s claim after finding absolutely no evidence to support it. Republican-coordinated voter suppression is hardly a new phenomenon in America, but the sheer brazenness of Kemp’s efforts to flout the democratic process has since made his name synonymous with the practice.

As governor, Kemp has pivoted from hollowing out democratic elections to simply cancelling them. At a moment when the death of Ahmaud Arbery has drawn national attention to the administration of justice in Georgia, he and other high-profile officials are exploiting legal loopholes to block voters from choosing new leaders for the state’s criminal legal system. Thanks to a series of eleventh-hour maneuverings, three of this year’s key races—two for seats on the state Supreme Court and another for a competitive district attorney race in his hometown of Athens—will not take place after all. Brian Kemp, instead, gets to decide them by himself.

—

Over the past few months, two of the Georgia Supreme Court’s nine justices have announced plans to resign from the bench, even though their terms were already set to expire at the end of this year. In December, Chief Justice Robert Benham revealed that he would retire on March 1; in February, Justice Keith Blackwell announced that he, too, would leave his post, effective on November 18, 2020. (As the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s Bill Torpy explains, this extended lame-duck period allows Blackwell, who previously made one of President Trump’s shortlists for the U.S. Supreme Court, to reach the 10-year service requirement necessary for his pension to vest.)

The Georgia Constitution gives the governor the right to fill temporary vacancies on, in theory, a temporary basis: Interim appointees to any “public office” serve the remaining balance of the term “unless otherwise provided by this Constitution or by law.” Otherwise, if a justice’s six-year term reaches its natural conclusion, an election takes place. Had Blackwell and Benham not quit, they would have been on the ballot this year, in a contest originally scheduled for May 19 and later postponed to June 9 for COVID-19-related safety reasons.

You might think these provisions would entitle Benham’s and Blackwell’s replacements to serve only through the end of 2020, spending a few uneventful months keeping the seats warm for their duly elected successors. That “unless otherwise provided” caveat is an important one, though, because the state constitution also specifies that appointees to elected judicial positions automatically get extra time in office, serving through the year of the next general election that is more than six months out from their appointment.

Put differently: If Brian Kemp makes you a Supreme Court justice with fewer than six months to go until an election for Supreme Court justice, that election gets bumped for two full years. Sure enough, on March 1, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger cancelled the contests for both seats on the grounds that Kemp would fill these vacancies himself.

The policy rationale for this loophole sounds sensible enough: It prevents rookie justices from having to learn the ropes of their new job while simultaneously running a hastily assembled campaign to keep it. But maneuvers like Blackwell’s and Benham’s are less about easing bureaucratic transitions than they are about transforming seats on the court into prizes for the governor to dole out as he sees fit. When resignations conveniently arrive this close to an election, Kemp gets to dispense entirely with the burden of holding one.

As absurd as it may seem, these strategic departures have become commonplace in Georgia over the past several decades. Eight of the nine current justices were originally appointed to their positions, including Carla Wong McMillian, the intermediate appeals court judge whom Kemp tapped to replace Benham; she will now serve until at least 2022. Georgia has not actually held a contested race for an open Supreme Court seat in nearly 40 years.

Benham’s departure is a textbook example of this informal spoils system at work, but Kemp’s bid to replace Blackwell is a more aggressive assertion of executive power. Since Blackwell is sticking around until November, appointing his successor amounts to “filling” a position that is not actually vacant, while in the meantime cancelling the already-scheduled, constitutionally prescribed method for selecting his replacement. Two Supreme Court hopefuls, former Democratic Congressman John Barrow and former Republican state lawmaker Beth Beskin, promptly sued to reinstate the election; with Blackwell still on the bench, they reasoned in separate complaints, they should be able to compete for his seat.

On March 16, however, a lower state court rejected their arguments, citing a provision of Georgia law that deems tendered resignations effective on the date the governor accepts them. This means that for the next six months, Blackwell will perform a job he legally does not have, and that Brian Kemp can act as an electorate of one whenever he gets around to it.

In a fun twist of appellate procedure, the next stop for Barrow and Beskin was the Georgia Supreme Court, likely giving Justice Blackwell’s own colleagues the final word on who picks their next co-worker. Given the obvious and multitudinous conflicts of interest, Blackwell and five other justices recused themselves from the case; lower court judges decided it in their stead. In an opinion published May 14, the Court upheld the lower court’s decision and refused to order that an election take place. Separately, a trio of disenfranchised Georgia voters has sued Raffensperger in federal court, asserting that cancelling the election functions as an “absolute restriction” on their right to vote; on May 5, the AJC reported that Barrow may make his case in federal court, too.

Benham’s and Blackwell’s seats were not the only two that would have been at stake this spring. Justices Charlie Bethel and Sarah Warren are on the ballot, too, and after Raffensperger cancelled the election for Blackwell’s seat, Beskin filed the paperwork to challenge Bethel. But the reluctance to take on incumbents is a testament to the significance of Kemp’s blessing for his appointees’ future electoral prospects: According to Torpy, no sitting Georgia Supreme Court justice has ever failed to win re-election.

—

Now, with the November general election fewer than six months away, Kemp is trying to pull off a similar stunt in a critical local prosecutor race. In February, Ken Mauldin resigned after serving nearly two decades as DA for Athens-Clarke and Oconee counties, leaving his deputy, Brian Patterson, temporarily in charge of the office. Given that Mauldin, a Democrat, had already announced he would not seek another term in 2020, the suddenness of his departure was curious; at the time, he explained that he felt a “strong pull” to begin a “new chapter” in his life.

Deborah Gonzalez, a former Democratic state legislator, quickly declared her candidacy and positioned herself as a progressive reformer, pledging not to seek the death penalty, prosecute marijuana possession, or charge women with violations of Georgia’s controversial “heartbeat bill” if she were to win the job. Patterson, also a Democrat, launched a bid to make his promotion permanent.

When a sitting DA steps down, state law requires the governor to appoint an interim DA until voters elect a permanent replacement to a four-year term in office. But under House Bill 907, enacted by the legislature in 2018, the same procedure Kemp is abusing to play Supreme Court kingmaker allows him to meddle in prosecutorial politics, too. If fewer than six months remain until a general election, an appointed DA gets to serve until the following general election—even, the statute says, if that period “extends beyond the unexpired term of the prior district attorney.” In other words, House Bill 907 allows the governor to postpone by two years DA races he doesn’t want to risk losing.

In his resignation letter, Mauldin claimed that he timed his announcement to avoid this outcome, and asked Kemp to make a decision “promptly” so the election could go forward as scheduled. Kemp, however, did no such thing. By failing to act by May 3, six months before Election Day 2020, he ensured that whoever he eventually picks won’t face a challenger until Election Day 2022 at the earliest. Gonzalez, the would-be reformer, will have to wait until then for a shot.

—

Kemp isn’t the first Republican governor to wipe a tough DA race off the ballot like this. In March 2018, after then-Governor Nathan Deal elevated Douglas County’s Republican DA to a spot on the state bench, two prosecutors—Republican Ryan Leonard and Democrat Dalia Racine—quickly jumped in the race. A head-to-head contest between the two seemed as if it would be, at the very least, close: When Racine challenged the incumbent in 2014, she lost by fewer than 500 votes out of 37,563 ballots cast. Hillary Clinton won the county in 2016, making a 2018 redux seem like a prime opportunity for a Democratic pickup.

The hasty passage of House Bill 907 that same month, however, allowed Deal and the Republicans to box out Racine and the Democrats altogether. In May, days after the six-month deadline passed, Deal handed the position to Leonard, the Republican. Racine is running unopposed for the position this fall—Leonard is not seeking another term in office—but the governor’s stalling will keep her on the political sidelines until then.

Aware of the debacle in Douglas County, Gonzalez publicly called on Kemp to name a successor soon after Mauldin quit; failing to do so, she said, would illegitimately stymie criminal justice reform efforts and “place backroom deals hatched by politicians in Atlanta before the people of Clarke and Oconee Counties.” Her campaign also threatened litigation, asserting in April that preempting the election would amount to a “silencing of the People’s voice.” When I spoke to her last week, she said her campaign is still reviewing its options going forward. I was unable to reach Patterson for comment.

—

No one person is responsible for these electoral disappearing acts. Instead, they are the product of a symbiotic relationship between legislators who are willing to enable political patronage, a governor willing to take advantage, and ambitious public officials who are willing to participate. The effect of these tacit agreements is to create a sham democracy in which voters rarely weigh in on who gets to interpret and enforce the law against them.

One only needs to glance at the headlines right now to see why these decisions matter: In Brunswick, a few hours southeast of Athens, it took two months and three different prosecutors before murder charges were filed in the death of Arbery, a 25-year-old Black man shot and killed while jogging by two white men stalking him in a truck. If not for a leaked video of the killing that went viral on social media, the shooters might have evaded the legal system altogether. Across the country, COVID-19 is whipping through overcrowded jails and prisons with unrelenting fury, turning punishments of all types into de facto death sentences. At this particular moment, voters in Athens might be especially interested in choosing the next person to wield prosecutorial power in their community; similarly, perhaps voters in Georgia would like to decide for themselves who will sit on the state’s highest court.

Brian Kemp’s bit of well-timed foot-dragging, though, forces voters to wait two more years to do so, effectively stamping out a nascent reform movement before it even had a chance to develop. Time and again, Kemp and the Republican Party have made clear that they view free elections not as legitimate checks on their job performance, but as tiresome obstacles to the Republican Party’s accumulation of power. The simplest method of keeping power, it turns out, is building a system in which it is never meaningfully at risk.

The article was updated on May 14 to reflect the Georgia Supreme Court’s new ruling on the cancellation of the election for Justice Blackwell’s seat.