Political Report

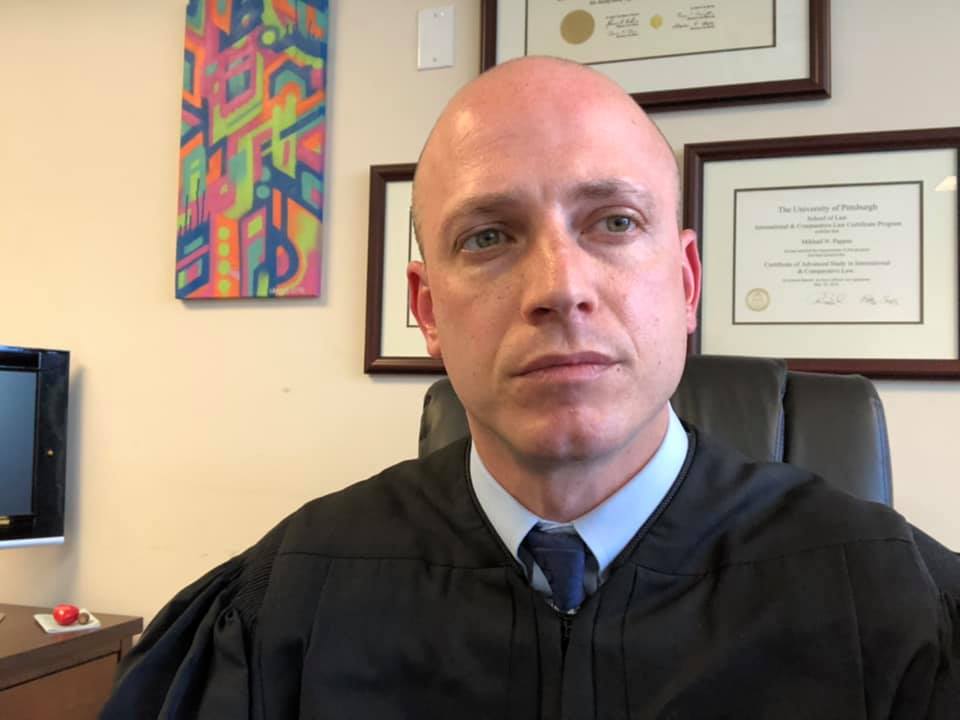

A Pittsburgh Judge Wants to Use the Bench To Fight Evictions and Mass Incarceration

Mik Pappas, elected judge in 2017 with the support of the local DSA, is now running for higher office as part of a slate that wants to change the legal system in Allegheny County.

Mik Pappas, elected judge in 2017 with the support of the local DSA, is now running for higher office as part of a slate that wants to change the legal system in Allegheny County.

Mik Pappas’s path to becoming a judge has not been typical. He has never prosecuted a case and instead spent several years as a community organizer campaigning against private prison corporations, helping people in county jails vote, and advocating for criminal justice reform.

In 2017, Pappas was elected as magisterial district judge in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania—which includes Pittsburgh—in an effort to reform the system from the inside. Pappas won with the support of the Pittsburgh chapter of Democratic Socialists of America.

“I knew the power of the law and making social change and in influencing society in a positive way,” he told The Appeal: Political Report.

Pappas has nearly eliminated the use of cash bail in his judicial district, reduced evictions, and found alternatives to issuing warrants and arresting people who owe money to the court. Now he’s seeking higher office as a common pleas judge, a position where he could influence judicial policies throughout the county.

Pappas is running as part of a slate backed by local activists who hope this election will reshape the court of common pleas, which has nine out of 34 seats open. Their first hurdle is a primary on May 18. The outcome could have an effect on issues from mass incarceration to evictions.

In Pennsylvania, common pleas judges are trial court judges. They hear and decide motions, oversee bench and jury trials, and render verdicts. They also handle civil cases, hear eviction appeals, and decide on final protection from abuse orders.

Common pleas judges have sway over magisterial district courts, whose judges are typically the first to hear a criminal case. Magisterial district judges sign off on warrants, set bail, and determine if there is enough evidence for cases to move on to the common pleas trial court. They also handle traffic citations, small claims civil suits, and landlord tenant cases.

This is where Pappas has already made inroads. He described his work at the magisterial district level as a proof of concept that showed judges can use their power to reduce the use of jails and harsh penalties.

A 2019 report from the ACLU of Pennsylvania found Pappas did not set cash bail in any cases between February and June 2018—his first few months in office. He set cash bail in only six cases during the same time in 2019. In total, Pappas set cash bail in less than 3 percent of cases that came before him during those 10 months.

For comparison, some judges in the county imposed cash bail in more than 70 percent of cases during the same time. The report also found glaring racial disparities in the use of cash bail; Black people accused of crimes were initially assigned bail more than 1.5 times more often than their white counterparts.

Outside of some criminal homicide cases which require bail to be denied, Pennsylvania law provides magisterial district judges with wide discretion over what kind of bail to impose, what conditions to set, and, if cash bail is used, how much the person charged is expected to pay before they can be released.

Pappas said he was able to essentially eliminate cash bail by working with people who are facing charges to craft conditions of release. He might issue an order to stay away from an accuser, or make a recommendation of releasing the person to mental health or social services. He says these measures allow people to remain out of jail while awaiting trial, help guarantee their appearance in court, and ensure they don’t cause harm.

“What this all has been is figuring out how the systems work, where the gaps are in the bail system and how to fill them,” he said.

Pappas has also taken an unusual approach to landlord-tenant disputes, which has resulted in a nearly 40 percentage-point reduction in the number of cases won by landlords in his judicial district.

He said he accomplished this in part by more strictly holding landlords to their burden of proof and requiring evidence that they have taken all the proper steps before asking that a tenant be forcefully removed from the property.

This helped cut down on the number of cases that resulted in eviction but also led to fewer cases being appealed by the tenants, Pappas said.

Pappas also began referring some cases to mediation in an effort to resolve a conflict between a landlord and a tenant in a way that didn’t require throwing someone out of their home.

With the COVID-19 pandemic bringing a halt to many eviction proceedings, Pappas said the county has turned to more mediation services to help resolve landlord-tenant conflicts.

Organizations like Just Mediation PGH have helped the court handle cases arising during the pandemic, and Pappas says he hopes mediation or other types of alternative conflict resolution will remain and expand after the pandemic is over.

“People are coming here because they have a conflict, not necessarily because they want the most harsh remedy available,” he said. “These are conflicts where an eviction would be like using a hammer to swat a fly.”

Pappas also instituted a fine and fee justice workshop that connected people who owed money to the court with financial planners and helped them set up payment plans and get in good standing with the court without risk of being arrested.

If Pappas wins a seat on the court of common pleas, he won’t oversee these cases anymore, but he says he wanted to seek the higher office because it will allow him to help shape policy for the entire county rather than just in his individual judicial district.

Pappas did not seek the county Democratic Committee nomination and instead joined two other candidates to create what they’ve called a Justice Reform Coalition. The coalition is made up of Pappas, public defender Lisa Middleman and former assistant district attorney Nicola Henry-Taylor.

He said their goal is to start building power at the common pleas level by electing judges who are interested in instituting reforms to make the system fairer.

The three have also become part of the Slate of Eight, a group of candidates endorsed by several progressive organizations.

If Pappas is successful, Governor Tom Wolf will nominate someone to fill his seat for the remainder of his term, which ends in January 2024. Wolf’s nominee is subject to confirmation by the Republican-led state Senate.

“As [a magisterial district judge], I wanted to push back against mass incarceration,” Pappas said. “But as a common pleas judge, what I’d be calling for is to end mass incarceration in Allegheny County.”

The article has been updated to reflect that Pappas does not describe himself as a socialist.