Police Often Use Force on Black People in Response to 911 Mental Health Calls

Media focus on killings obscures many cases of non-fatal force, MindSite News-Medill investigation shows.

This story was produced by MindSite News, an independent, nonprofit journalism site focused on mental health. Get a roundup of mental health news in your in-box by signing up for the MindSite News Daily newsletter here.

This story is the latest installment of Fateful Encounters, an ongoing investigative collaboration between MindSite News, the Medill Investigative Lab-Chicago at Northwestern University and other media outlets exploring police response to mental health crises. This work is generously supported by the Sozosei Foundation.

Louisville yoga instructor and artist Kabira Yakini was having a rough day.

Her teenage son had recently run away from home and, as she describes it, “I’d been looking for a job for a year. Just the weight of everything, a lot was going on.”

That day—Jan. 4, 2024—she shut herself in her room and went on Facebook Live to vent, saying she wished she and her children could leave this earth, painlessly. She just needed to let off steam, but “somebody took that as I was going to do something.”

Soon, officers from the Louisville Metro Police Department were knocking on the front door. Yakini told them she was fine and not planning to hurt herself. But three officers forced their way in and told Yakini they were going to take her to the hospital involuntarily, even though she told them her sister was on the way and she was willing to go voluntarily with her sister.

Yakini refused to go with the officers. For more than a decade, she told MindSite News, she’d been “boots on the ground” as an activist fighting police mistreatment of Black people, and she didn’t trust law enforcement to help her, especially since all three officers were white.

“I’m not letting you all kidnap me,” she said, recounting the interaction. “Black women, Black people end up dead in your all’s care, and I’m putting care in quotation marks.”

As captured on her phone video, an officer pushed through the door and threw Yakini to the ground, banging her head, then loaded her in a police cruiser.

She was released from a hospital and spoke at a press conference the next day calling for better response to mental health crises. The encounter has left her with depression and despair at the lack of accountability for how she was treated, Yakini told MindSite News.

“This wasn’t okay,” she said. “I know they do many other people like this who do not have a voice, who cannot speak up for themselves.”

Stories of people being killed by police while experiencing a mental health crisis, especially Black people, frequently make the news and spark outrage—like the July 6 killing of Sonya Massey, an unarmed woman with a history of mental illness who was shot by police officers in her kitchen in Springfield, Illinois. Over the past 10 years, starting Jan. 1, 2015, the Washington Post has documented the killing by police of 2,053 people experiencing a mental health emergency. But there are far more situations like Yakini’s where non-fatal force is used, which can also leave lasting physical and mental impacts.

For every death, scores of less-than-fatal incidents

In fact, looking at data from just 16 cities during that same decade, a joint investigation by Medill Investigative Lab-Chicago and MindSite News has identified almost 5,000 incidents in which people experiencing mental health crises were beaten, shocked by a Taser, shot but survived, or had another form of non-fatal force used against them. In those 16 cities, for every fatal encounter between police and a person experiencing a mental health crisis, non-fatal force was deployed against 78 people.

The investigation also found that in these crisis situations, police used force against Black people—especially Black men—at rates vastly disproportionate to the racial demographics of their cities. Often, these less-than-lethal incidents garnered little or no media attention.

From 2017 to 2022, police in Portland killed five people in the midst of a mental health crisis, according to the Washington Post database. During the same time period, police used a less than lethal form—such as a takedown, bean bag gun or pepper spray—against more than 700 people going through such crises, our analysis found.

Similarly, from August 2020 through August 2024, Chicago police fatally shot one person in the midst of a crisis, according to the Washington Post database. During the same period, Medill and MindSite News found, Chicago police used force—tasers, batons, non-fatal gunfire, handcuffing—on more than 150 people after someone called 911 for help in a mental health-related incident.

In San Diego, from 2016 to 2022, eight people were killed by police while in crisis, while more than 1,500 were subjected to less-than-lethal force after a 911 mental health-related call.

(Medill and MindSite News requested data on mental health-related 911 calls and use of force from the 100 largest US cities from 2010 to present. In response to those requests, more than 30 cities provided such data for varying date ranges, and in 16 of those cities, the data was sufficient to figure out when specific 911 calls resulted in use of force.)

Disproportionate use of force in 13 of 16 cities

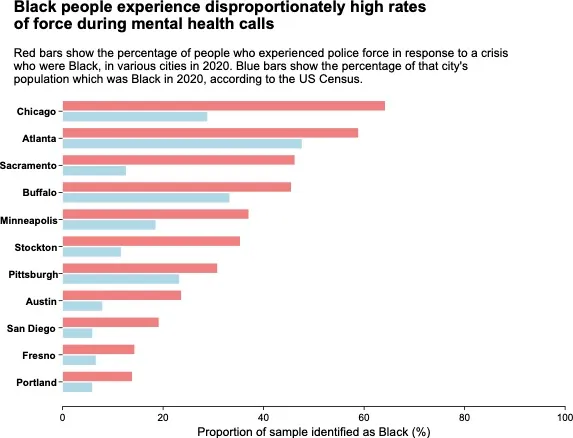

In 13 of the 16 cities where it was possible to analyze the race of people subjected to police force, Black people made up a higher percentage of those incidents than they represent in the city’s population, usually by significant margins:

- In Chicago, Black people comprise 27 percent of the population but experienced two-thirds of the use-of-force incidents that occurred pursuant to a mental health-related 911 call from August 2020 through August 2024.

- In Portland, Black people make up just 6 percent of the population but were subjected to almost a fifth of the use-of-force incidents from 2017 to 2020.

- In Minneapolis, Black people make up 19 percent of the population but represented more than a third of such incidents from 2008 to 2023.

- In Buffalo, Black people make up 32 percent of the population but experienced more than 40 percent of force incidents from 2012 to 2023.

- And in Stockton, Calif., where Black people are 13 percent of the population, they experienced almost a third of the use-of-force incidents from 2015 to 2023.

Miami, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, San Diego, Sacramento and Austin also showed disparities. Of the 13 large cities providing data including race, Cincinnati was the only one where Black people were not overrepresented in the use-of-force tallies connected to 911 crisis calls. Our analysis of data provided by the Cincinnati Police Department showed force was used 37 times in response to a mental health call from 2015 to 2021, and all the subjects, according to the department’s data, were white.

The Washington Post database of fatal shootings by police also shows racial disparities. Of the 2,053 people with signs of mental illness fatally shot by police between the start of 2015 and the end of 2024, 336 of them, or 17 percent, were Black men, who make up about 7 percent of the US population.

We see similar tropes: Black men are more ‘threatening’ and perceived to be carrying deadly weapons and people with psychiatric disabilities are risky, inherently dangerous, prone to violence.”

Jamelia Morgan, Northwestern university law professor

Most people with mental illness are not violent. Studies suggest that only 3 percent to 5 percent of violent acts are perpetrated by individuals with a serious mental illness, and that people with mental health problems are about 10 times more likely to be victims of violent crime than the general population.

But experts say that stereotypes of criminality and violence are often associated with people of color and people with mental illness. People who fit into both categories may have limited access to mental health resources and are often trapped in a cycle of spiraling crises that lead to encounters with law enforcement.

“We see similar tropes: Black men are more ‘threatening’ and perceived to be carrying deadly weapons…and people with psychiatric disabilities are risky, inherently dangerous, prone to violence,” said Jamelia Morgan, a law professor at Northwestern University and founder of the school’s Center for Racial and Disability Justice. She added that this “constellation of stereotypes” can mean that when police respond to Black men in crisis, “there is fear, a turn to force—not a turn to de-escalation tactics.”

One example: In July 2022, Ernso Prinvil, an unhoused Black resident of Atlanta, was walking through traffic naked when an officer approached him, then began chasing him and yelling out orders. Prinvil ignored the orders and walked towards the officer with “a clenched fist and fighting stance,” according to the police report.

Though Prinvil was clearly unarmed, the officer fired his Taser, striking Prinvil in his stomach and genitals. Officers handcuffed him, then called for medical help to remove the Taser prongs from his genitals. Prinvil was later charged with disorderly conduct and public indecency.

Encounters between law enforcement officers and Black people in mental health crises often play out in similar ways, said Brian Dunn, a California-based civil rights attorney who specializes in cases of police misconduct. Police respond to calls about someone experiencing a mental health crisis, view the individual as a threat, shout orders and draw their guns or Tasers, he said.

The person in crisis feels threatened and goes into a fight-or-flight state. They struggle to understand the officers’ orders and don’t know how to react. Police interpret this as noncompliance or resistance and escalate their tactics, Dunn said.

“The police are unable to understand that the person they’re speaking to doesn’t understand them,” Dunn continued. “That’s a volcanic situation, and it’s going to erupt very easily.”

Police accountability lacking

Internal and local investigations into police use of force against civilians in mental health crisis frequently arrive at the same conclusion: It was justified.

But those affected by such force—whether survivors or loved ones—often demand more accountability for the officers involved.

In 2010, a police officer in Portland, Oregon, shot an AR-15 and killed Aaron Campbell, a Black man experiencing a suicidal crisis. A grand jury decided the officer who killed Campbell was justified in using force and should not be criminally charged. In an exception to the norm, Portland’s police chief terminated the officer and gave an 80-hour suspension to other officers present during the shooting.

The officer who killed Campbell was reinstated in 2016, and is still active on the force. In 2023, he passed the department’s required mental health training.

Campbell’s death triggered an investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), which sued the city and its police bureau in 2012 for excessive use of force on people experiencing mental health crises. The city reached a settlement in 2014, and ever since, an independent monitor has published quarterly compliance reports.

But use of force following mental health-related 911 calls continued, leading to the killings of Andre Catrel Gladen in 2019 and Michael Townsend in 2021. Gladen was blind in one eye and lived with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, according to family members. A grand jury found the officer who tased and then fatally shot Gladen acted in self defense and should not be prosecuted, after hearing evidence that Gladen grabbed a knife from the officer’s vest.

In other cities, legal settlements aimed at reducing the use of force against people experiencing mental health crises have also failed to do so.

A ‘culture of aggression’

The DOJ has been monitoring the Albuquerque Police Department for more than a decade. This led to a 2015 consent decree requiring the city to change how officers deal with mental health crises. In 2020, the city launched a mobile team to respond to mental health crises without police. In October 2024, the DOJ found Albuquerque to be in almost full compliance with the consent decree.

But Albuquerque’s mobile team doesn’t operate around the clock, so police still respond to many mental health-related calls, The New Yorker reported in 2023. Fatal shootings of people in mental health crisis have continued, with 10 since 2020 and five in 2022 alone, according to the Washington Post database.

The police department said six people shot by officers in 2022—ncluding one non-fatal shooting—“had a history of mental health calls and several were in the midst of an apparent mental health crisis when they were shot,” the Albuquerque Journal reported. (MindSite News and Medill obtained use-of-force records and mental health call records from Albuquerque, but the data was not sufficiently detailed to match individual mental health calls to 911 with subsequent use of force.)

The police in Albuquerque operate in a “culture of aggression” that “lacks accountability and seeks to evade accountability for police,” Daniel Williams, a policing policy advocate at ACLU New Mexico, told MindSite News. “That certainly was the case in Albuquerque 10 years ago when the consent decree started, and (it) remains a big concern.”

Chicago’s 2017 consent decree—resulting from a federal investigation that found racial discrimination in policing—also includes detailed requirements for the use of crisis response and training. It instructs 911 dispatchers to identify and direct crisis calls straight to officers with Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training meant to help them deal with mental issues. But in 2023, the court-appointed monitor reported that a required crisis response unit was “severely understaffed,” and that the city had not filed mandatory annual reports on crisis intervention since 2020.

‘They escalated things. They should not have been there’

In Louisville, a federal consent decree issued last year requires the police department to adapt training and policy changes—including use of de-escalation techniques during mental health crises. The DOJ’s investigation, prompted by the 2020 police killing of Breonna Taylor, revealed a long history of anti-Black racism and assault on people with disabilities by Louisville police.

But uses of force against Black people in crisis have continued—as Kabira Yakini’s experience shows. Louisville has a crisis response program that sends clinicians instead of police, but Yakini later learned her case wasn’t eligible because a third party had called 911. Yakini helps run a grassroots organization that provides mental health and other services to Black single mothers. She would like to see these groups and clinicians play a greater role in crisis response efforts.

Police should not be responding to mental health crises on their own, Yakini told MindSite News. “They escalated things. They should not have been there.”

In Chicago, Mayor Brandon Johnson recently removed police and fire personnel from its alternate response program, delivering on a campaign promise to remake the program started under the previous mayor, Lori Lightfoot. The changes were made with input from organizers in the Treatment Not Trauma movement, which has been working since 2012 to reopen closed community mental health centers on the city’s south and west sides and to remove police from mental health crisis response teams.

A movement grows in Chicago

Johnson, who is Black, often talks about losing his brother, Leon, who “suffered from mental illness and died addicted and unhoused.”

These changes are an effort to reverse entrenched racial and geographic patterns. A significant majority of mental health-related calls to 911 over the past four years came from mostly Black neighborhoods on the south and west sides of Chicago, according to the MindSite News-Medill analysis.

“On the South Side, there were people who had no other option than to walk into the police station” during a crisis, said Amy Watson, a professor of social work at Wayne State University in Detroit. “We didn’t hear that on the (largely white) North Side because people have other places to turn before they turn to the police.”

Watson’s research has led her to conclude that the presence of police in responding to mental health crises “tends to delay responses and escalate situations,” as people—hoping to avoid summoning police—delay seeking help until a situation becomes dire. With more options for alternate response, she said, people trained in crisis response could help defuse a situation earlier on.

Morgan, the Northwestern law professor, argues that investment in mental health care for underserved Black communities must be done in tandem with alternate response programs.

“The lack of behavioral health infrastructure makes it so only the police are providing the service. They become a go-to for crisis care services, and that poses a barrier to reform,” she said. “There are so many ways you could invest more resources, not in the law enforcement response, but in the services people need to maintain good mental health.”

Morgan and other advocates argue that crisis response teams should include people from the same communities and backgrounds as those in crisis. In Miami, a private nonprofit organization is doing just that.

Dream Defenders offers a different path

On March 7, 2023, Denise Armstrong called Miami police to seek help for her son, Donald Armstrong, who was going through a mental health crisis. Police arrived and tried to talk with Donald, a 47-year-old Black man, but he was not following orders and had a screwdriver in his hand. He lifted his shirt, showing he was otherwise unarmed. His mother, seeing the situation escalate, begged officers not to shoot her son.

To no avail: Armstrong was shot at least six times on his mother’s porch, leaving him paralyzed from the waist down. He was arrested and held in a jail medical unit, charged with aggravated assault and resisting arrest. The final remaining charges were dropped in October.

Just four streets over from Armstrong’s home is the office of Dream Defenders—a grass-roots advocacy and action organization led by Black women that was founded in the aftermath of the 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin. The group runs the Freedom House Mobile Crisis Unit, which responds to mental health crises without involving police in the majority-Black Liberty City neighborhood. See a deeper exploration of the Freedom House mobile crisis program here.

Chettarra Thompson, the mobile crisis manager, sees Donald Armstrong’s case as an example of the dangers people experiencing a mental health crisis may face at the hands of police.

In 2023, Freedom House teams handled 116 crisis interventions, providing counseling and referrals to 35 percent of subjects and transporting 20 percent to the nearest hospital, according to the organization’s 2023 annual report. Team medics provided direct medical care to another 15 percent. Among those served, 83 percent were Black, 12 percent were Latino and 61 percent were male.

“We try to focus on answering calls with urgency and make sure that we are responding with care and empathy,” Thompson said.

Support for this investigation was provided by the Sozosei Foundation. Josh McGhee’s work was supported by a 2023-2024 Rosalynn Carter Mental Health Fellowship.

This investigation was produced by MindSite News Chicago Bureau Chief Josh McGhee, student journalists at the Medill Investigative Lab-Chicago at Northwestern University and Medill Assistant Professor Kari Lydersen. The student journalists reporting this story were: Glendalys Valdes, Melissa Dai, Audrey Azzo, Shannon Tyler, Catherine Odom, Stephana Ocneanu and Adam Babetski. Valdes reported from Miami; Azzo reported from Portland; Ocneanu reported from Austin. Data analysis was led by Arne Holverscheid, with data analysis assistance from Aaron Geller, Yangyang Li and Colby Witherup Wood, all from Northwestern University IT Research Computing and Data Services (RCDS). Data visualizations by Yangyang Li and Arne Holverscheid.

Additional reporting by Medill students Jacob Danielson, Jahlynn Hancock, Allende Miglietta, Louise Kim, Jennifer Bamberg. Additional public records research conducted by Medill students Natalia Salazar, Amelia Schafer, Kelliann Duncan, Alex Harrison, Claire Foltz, Calvin Krippner, Emeline Posner, Khadija Ahmed, Felicity Huang, Alex Perez, Kadin Mills, Sela Breen and Rob Reid.