Philly Cops Are Solving Fewer Homicides. The City Keeps Paying Them Millions

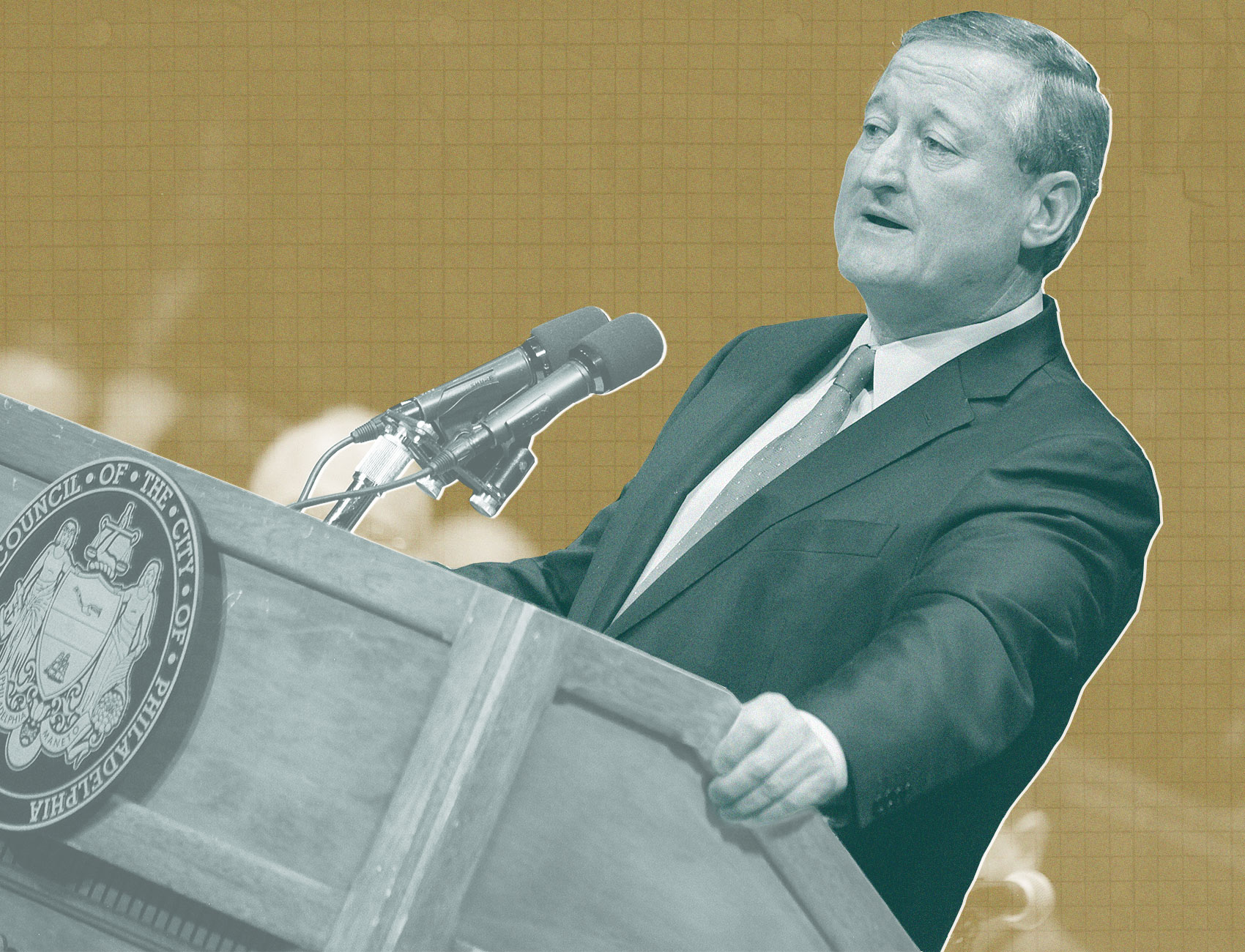

Community members and advocates question why Mayor Jim Kenney and the City Council continue to fund the police department at record levels, despite the department’s low murder solve rate.

Between 2013 and 2020, the Philadelphia Police Department budget rose by nearly a quarter. At the same time, murders doubled, but police only solved half of all murders in the city.

Community members and lawmakers want to know why those who control the city’s budget—the City Council and the mayor in particular—keep funneling money into a department that they say is failing to keep the community safe.

During last summer’s protests against police violence in the wake of George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis, the nation’s mayors drew scrutiny for their role as the elected official who oversees and sets the tone for the police department. But mayors are less often held accountable for ensuring police are fulfilling one of their core functions: solving the most serious crimes.

“Mayors are part of a political apparatus that is in many respects much more in control of these harms than the police are,” Alec Karakatsanis, founder and executive director of nonprofit group Civil Rights Corps, told The Appeal. “The police are a bureaucracy wielded by local governments to achieve specific goals.”

In Philadelphia, despite ballooning budgets, the rate at which police solve the most serious crimes has plummeted over the last four decades.

In the 1980s, Philadelphia police cleared nearly 80 percent of all murders. Between 2010 and 2015, that number had declined to 65 percent before falling to below 50 percent in the years since 2016, where it has stayed ever since.

Clearance rates for assaults with a firearm have also fallen substantially from a high of 86 percent in 1969 to less than 20 percent last year.

As the city’s chief executive, Mayor Jim Kenney, a Democrat, oversees the police department. He has the authority to hire and fire the police commissioner, to veto legislation passed by the City Council, and use his position to bring stakeholders together, said Diane Goldstein, executive director of the Law Enforcement Action Partnership and a retired police lieutenant.

One area in which Kenney wields significant authority is in the city’s budget process. Each year in March, Kenney proposes a budget, but he also can influence the final budget passed by the council. Like all cities, Philadelphia has scarce resources. Therefore, when it comes to preventing and mitigating violence, the budget question is: Does the city allocate more dollars to the police department or, instead, provide resources to other critical community services and programs?

“Government budgeting is a reflection of the values of the city,” Goldstein said. “Sometimes it’s just easier to throw this money at the police and let them solve it, but that’s shortsighted.”

Kenney’s 2021 budget initially called for a more than $3 million increase for the police in March and then a more than $11 million increase in May while cutting funds to homeless services, public art programs, and mental health services. He scrapped both plans in favor of budget cuts after protests in the city, sparked by the police killing of Floyd in May.

Dave Kinchen, spokesperson for the mayor’s Office of Violence Prevention, said Kenney was not ready to discuss his latest budget yet, but the mayor was “committed to investing as much as we can in education and social services that prevent violence, while upholding our commitment to public safety and enacting necessary police reforms.”

Kinchen also pointed to Kenney’s successful 2017 effort to re-establish the city’s police advisory commission, which is supposed to investigate residents’ complaints about police and provide guidance for Kenney. But some City Council members have said the commission lacks authority to make any real changes. And Kenney himself proposed cutting the board’s funding by about 20 percent in his 2021 budget. (The final budget included a roughly 40 percent increase for the commission.)

Although the City Council voted to cut the police department’s budget by $22 million for the current fiscal year, it now stands at $727 million—the second-highest police budget in 20 years. For comparison, the city spends less than $160 million from its general fund on the Department of Public Health and less than $55 million on parks and recreation.

City Council member Kendra Brooks, who voted against the budget, questioned continually spending so much money on law enforcement, who she said has overpoliced nonwhite communities through excessive arrests for minor offenses like drug possession, yet underprotected them from serious violence. Since 2018, Philadelphia police have made more than 12,000 arrests for drug possession alone, according to data published by District Attorney Larry Krasner’s office.

“We’re writing blank checks and not getting a return on our investment,” Brooks told The Appeal.

A similar dynamic has played out in other major U.S. cities. In Houston, the police department’s budget has risen by nearly $300 million since 2013 despite murder clearance rates plummeting. In 2011, the department cleared nearly 90 percent of all murders and had never had a year below 55 percent. But, since then, the clearance rate has been cut in half and fewer than half of all murders result in an arrest.

Cleveland increased its budget by $10 million between 2016 and 2018 while solving less than 20 percent of murders during that time.

Nationally, the homicide clearance rate fell from 72 percent in 1980 to 64 in 2008 and now sits around 60 percent, despite significant expansions in spending on technology and personnel, like forensic crime labs, that are supposed to help solve serious crimes.

“When policing appears to be working, the argument is we just need more of that,” Alex Vitale, professor of sociology at Brooklyn College and author of “The End of Policing,” told The Appeal. “When policing doesn’t appear to be working, because crime rates are going up, then the argument is we just need more of it. No matter what happens, they will argue that’s a justification for more money for policing.”

Vitale described that dichotomy as a political problem that requires political leaders to push for solutions outside of policing to address violence and harms in the community. This includes providing funding for housing, public health services, and employment programs.

“[Police] are not held accountable for performance or lack thereof,” council member Brooks said.

Police have blamed a lack of cooperation from witnesses as the reason for the city’s low solve rate.

But community members should not be at fault for the police’s failure to solve crimes, said Robert Saleem Holbrook, executive director of the Abolitionist Law Center. He called it a “cop-out” to blame the low solve rate on “a community that has been traumatized by the violence, has been traumatized by the harm, has been traumatized by mass incarceration and police.”

A recent survey found that a majority of Philadelphia residents did not believe the police department was good at preventing violence. The feeling was even more extreme in communities affected by gun violence. More than 80 percent of residents in those neighborhoods believed the police were bad or very bad at preventing violence.

“If you go to North Philly, Southwest Philly, where right now there’s wars going that constitute a majority of the homicides in Philly, you go down there with those statistics and they’re like ‘it’s always been like this,’” Holbrook said.

Frank Vanore, chief inspector of Philadelphia police, told The Appeal that after the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, “there were a lot of people who didn’t want to be a witness and had issues coming forward.” He acknowledged that lack of cooperation from witnesses was at least in part because of lack of trust between community members and police, and that the police department needs to undertake efforts to rebuild trust.

According to Vanore, the department’s homicide clearance for 2021 as of Feb. 17 was up slightly to 50 percent. However, the clearance rate was around 60 percent at the same time last year and the year ended below 50 percent.

The inability of police to solve violent crimes contributes to the community’s lack of trust and in turn an increase in violence, according to Richard Rosenfeld, criminologist at the University of St. Louis.

“People expect the police to protect them from crime and quite obviously from violent crime,” he said. “When the perception spreads that they are not able to solve those cases, that diminishes confidence in the effectiveness of police.”

Brooks, the Philadelphia City Council member, said that instead of continually increasing the police budget without seeing added benefits for public safety, the city could be putting some of that money toward addressing the root causes of violence by investing in quality education, reducing unemployment, increasing food security, and providing more stable housing.