As Major Cities Decarcerated During COVID-19’s Spread, Philadelphia’s Jail Population Barely Budged

The city’s DA’s office and its public defender association urged judges to adopt video meetings to speed the release of incarcerated people. But emails obtained by The Appeal show that judges took a much more limited approach to decarceration.

As early as March 11, the Philadelphia district attorney’s office and the Defender Association of Philadelphia requested that the city’s court system develop a plan to reduce the population of Philadelphia’s county jails before the novel coronavirus ravaged incarcerated people.

Instead, according to a trove of emails, data, and documents obtained by The Appeal, judges with the First Judicial District of Pennsylvania stalled plans that would have quickly decarcerated Philadelphia jails—and then appeared to have lied about aspects of their own response in an April 3 press release.

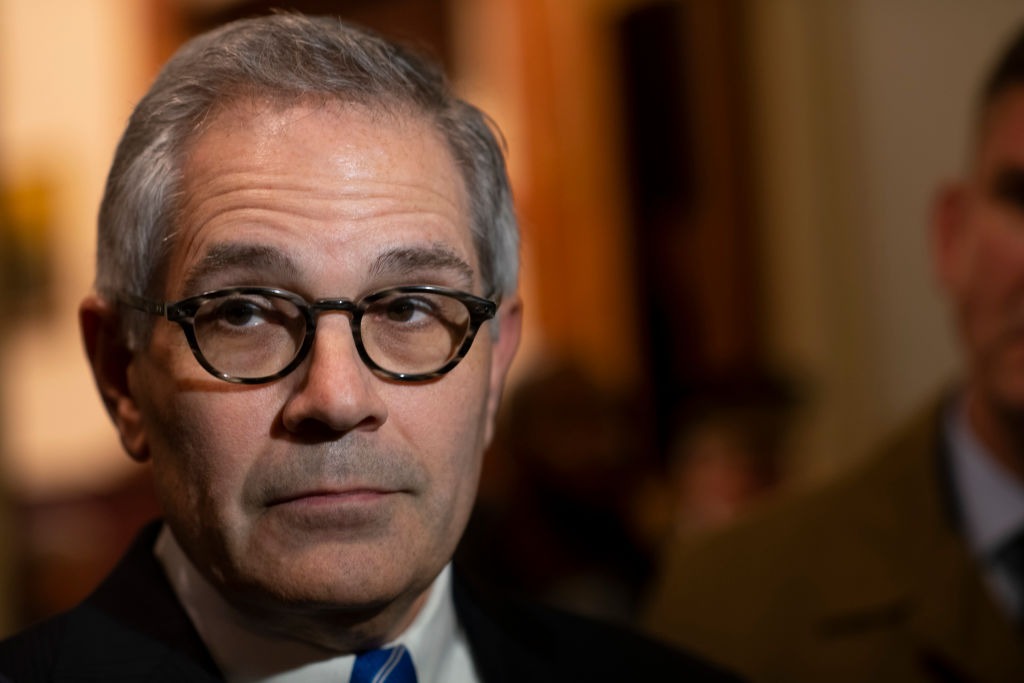

In the press release, Municipal Court President Judge Patrick Dugan said judges waited “for weeks” to receive lists of incarcerated people to release. Dugan implied that, without these lists from District Attorney Larry Krasner’s office, Philadelphia’s courts could not begin to reduce the number of incarcerated people amid the outbreak. But emails obtained by The Appeal show that by April 3, the DA’s office had supplied the names of nearly 2,000 incarcerated people to the First Judicial District.

As a result, only about 7 percent of the city’s approximately 5,000-person jail population had been released as of April 3. Since the COVID-19 outbreak began, Philadelphia County has released a smaller percentage of its incarcerated people than virtually every other major city in America. For example, according to CBS News, Los Angeles County released 10 percent of its jail population in a matter of days in March. Last month, New Jersey Supreme Court Chief Justice Stuart Rabner signed an order calling for a nearly 10 percent cut in the entire state’s local jail population. On April 6, San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin tweeted that his city’s jail population had been cut by roughly 38 percent since January. In Bucks and Delaware counties—neighbors to Philadelphia—jail populations were cut 20 and 35 percent.

“The District Attorney’s and Public Defender’s offices tried to get the leadership of the First Judicial District to handle lists of inmates without using these time-consuming written motions,” Krasner told The Appeal. “The judicial leadership repeatedly said no and rejected that suggestion until way too late.”

The inaction on decarceration comes as COVID-19 spreads in Philadelphia’s jails. As of April 8, at least 62 incarcerated people have tested positive for the disease in the Philadelphia Department of Prisons and hundreds more have been placed in quarantine after coming in close contact with individuals who tested positive. According to a dataset from the Defender Association of Philadelphia, as of April 4 the infection rate in Philadelphia jails—8.9 infections for every 1,000 people–was significantly higher than peak infection rates in New York City; Wuhan, China; and the heavily impacted Lombardy region of Italy.

Multiple other sources who declined to speak on record privately expressed frustration that the First Judicial District spent the last month stalling efforts to decarcerate that could have saved people from the coronavirus.

Ronald Greenblatt, a Philadelphia attorney who represented the city’s private defense lawyers in discussions with the First Judicial District, told The Appeal that the city’s prosecutors, public defenders, and private defense attorneys felt they could have started safely releasing a significant number of incarcerated people as early as March 16.

“We were ready to do whatever was necessary on behalf of our clients,” Greenblatt said. “We would have been ready to go that Monday, the 16th. We would have been there Saturday or Sunday even—there’s no off-days on this.”

Gabriel Roberts, a spokesperson for the First Judicial District, did not respond to repeated requests for comment from The Appeal.

On March 11, Krasner’s policy adviser, Dana Bazelon, emailed representatives for the court system and defender’s office, according to emails obtained by The Appeal. She asked for a meeting the next day to discuss how to best handle the emerging outbreak. In a March 20 recap, Bazelon wrote that Krasner suggested setting up a review process to release people from jail before the outbreak hit, but the courts were “initially not open to those proposals.”

Bazelon wrote that Philadelphia judges also refused to consider deferring low-level weekend jail sentences (for people with DUIs or other small infractions) and refused to defer turn-in dates for people about to serve longer sentences. Bazelon wrote that Judge Leon Tucker, who supervises the district’s criminal court division, threatened to shut down any expedited COVID-19 hearings if the DA’s office were to “bring [him] bullshit.”

In a March 20 email, Judge Idee Fox, president judge of the First Judicial District, also told the DA’s office that the courts were not yet treating motions for early parole and probation as “an emergency” during the outbreak.

Bazelon wrote in her recap that Judge Tucker complained in a March 19 conference call that he had been sent more than 50 parole petitions to review amid the outbreak.

“At one point Judge Tucker said it was ‘too much’ for him to review the petitions and that ‘it can wait’ until the courts are up and running,” Bazelon wrote.

On March 24, Judge Tucker vacated his previous order that would have transported Walter Ogrod—a Pennsylvania death row prisoner exhibiting symptoms of COVID-19 who Krasner’s office believes is “likely innocent”—to an outside hospital for treatment and testing. Ogrod’s prosecution for a 1988 murder was plagued by Brady violations, false confessions, and unreliable jailhouse informant testimony. (Tucker did not respond to emails from The Appeal this week. On Thursday, Judge Shelley Robins New denied a joint emergency motion to hear Ogrod’s case remotely, and as a result, it will not be heard until June 5).

On March 31 and April 2, Krasner’s office sent several spreadsheets of potentially releasable people to the First Judicial District and Defenders Association, according to emails obtained by The Appeal. On March 31, the head of Krasner’s pretrial division, Liam Riley, supplied the court system with a list of 92 people awaiting trial whom the DA’s office had agreed to immediately release via bail reductions.

Two days later, Krasner emailed 14 additional spreadsheets of names to the First Judicial District. Those documents included, among other data, 196 people with just six months of their minimum sentences left; 853 people held pretrial on less than $50,000 bail for charges that didn’t include violence, sex offenses, or drugs; 189 people incarcerated past their minimum sentencing requirements; 572 people held on probation-violation detainers without any underlying charges; and 151 mothers with children. Of the women with children, 113 were held pretrial.

On April 1, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court issued a directive that, among other things, strongly encouraged court systems around the state to use “advanced communication technology to conduct court proceedings, subject only to constitutional limitations. Advanced communication technology includes, but is not limited to: systems providing for two-way simultaneous communication of image and sound; closed-circuit television; telephone and facsimile equipment; and electronic mail.”

Prosecutors and public defenders tried to follow that directive. On April 2, Krasner emailed Greenblatt, the Defender Association, and the First Judicial District to inform them all that he and Keir Bradford-Grey, the Defender Association’s chief defender, had worked out a plan to hold virtual courts using Zoom teleconferencing software. During those proposed hearings, judges, prosecutors, and public defenders would have been able to make snap-judgments about who to release—without any written motions. The proposed process could have released hundreds of people per day.

“Specifically, the DAO [district attorney’s office] will be proposing again that we move beyond individual, written motions with written responses (in one form or another) to the expedited, case-by-case consideration by the court of lists of inmates many of whom will be worthy of release,” Krasner wrote. “The DAO’s idea is that a process determined by judicial leadership could immediately allow a group of judges presiding by Zoom to hear oral motions and responses from counsel on both sides and make careful, but quick case-by-case determinations after resolving any of the court’s questions on each case.”

Krasner then forwarded the 14 spreadsheets and wrote that he would be open to adding more names to them at a later date as well. The email was addressed to numerous judges, including Fox and Municipal Court President Judge Patrick Dugan.

In a second April 2 email addressed to Fox, Tucker, Dugan, Bradford-Grey, and others, Krasner again asked the courts to consider “expanding the program to include the 1,997 or so inmates reflected in our previously provided lists.”

But instead, on April 3, the First Judicial District system announced via press release that it would set up four courtrooms for just three days during the opening week. According to emails obtained by The Appeal, each courtroom will hear just 30 cases a day, a far slower pace than both prosecutors and defenders had hoped for. (On April 13, the First Judicial District will begin running seven courtrooms five days per week.) Judge Dugan also claimed in a written statement that the courts had asked Krasner’s office “for weeks” for lists of people who could be released but had not received them.

“For weeks the courts have sought from the District Attorney’s Office an agreed upon list of individuals whose cases were deemed sufficiently appropriate for review and possible release, as well as an agreed upon method and criteria by which to conduct the reviews and determine release,” Dugan said in the statement. “While the Courts continue to await a list of specific cases for review, we are encouraged that all parties are moving in the right direction.”

Spokespeople for the First Judicial District did not answer multiple emails from The Appeal asking about Dugan’s claims. But Krasner told The Appeal that the press release was “an inaccurate and unfortunate rewriting of history after the crisis has arrived.”

As Philadelphia jails have failed to decarcerate, conditions of confinement have become increasingly dangerous. On April 3, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported that at least nine quarantined people held inside the Philadelphia Industrial Correctional Center threw commissary containers at windows in an attempt to break the glass and escape.

Rania Major, a Philadelphia defense attorney, told The Appeal that the city’s jail system was a “pressure-cooker” and that medical personnel will become overwhelmed over the next few weeks if more people aren’t released.

“The people inside are petrified, just absolutely petrified,” she said. “One of my clients literally called me crying this week asking me to get him out of there.”