People In Prison Are Uniquely Vulnerable To Tainted Water

Months or years can go by before officials admit that water is unsafe for drinking.

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal.

The Arizona Department of Corrections confirmed this week that water at the Douglas Prison, where more than 2,000 people are held, had a “noticeable petroleum odor and taste,” reported Jimmy Jenkins of KJZZ-FM. The prison had been supplied with water from a new well after a water outage in June. The Department of Corrections spokesperson said the county has switched the prison’s water supply back to the old well. People held at the prison had “told their families the water was burning their skin after showers and causing diarrhea,” reports Jenkins. At the time of publication Monday, KJZZ still awaited details from Cochise County and the state Department of Environmental Quality.

Five years ago, contaminated water was piped into homes in Flint, Michigan. This was the result of a decision by the state’s emergency manager to switch the city’s water supply. For months, local and state officials insisted that the water, despite its suspicious taste, smell, and feel, was safe to use. By the time government officials conceded that something was dangerously wrong with the water, there had been 12 cases of Legionnaires’ disease and blood testing of children at the local hospital showed elevated lead levels.

In her book “The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy,” journalist Anna Clark wrote that the Flint water crisis “was not because of a natural disaster, or simple negligence, or even because some corner-cutting company was blinded by profit. Instead, a disastrous choice to break a crucial environmental law, followed by eighteen months of delay and cover-up by the city, state, and federal governments, put a staggering number of citizens in peril.”

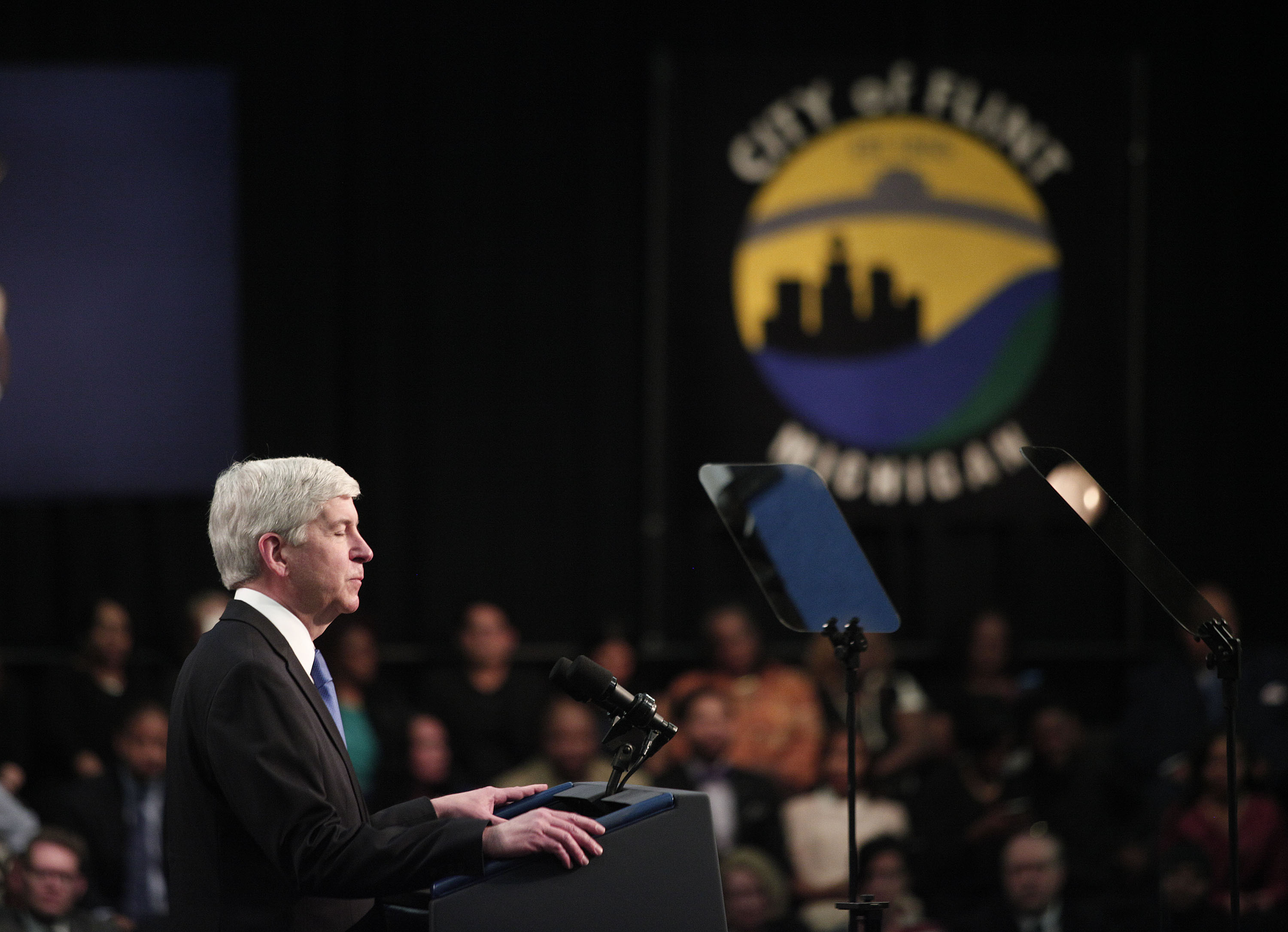

Although Flint became a byword for government negligence and cover-up, as well as for citizen action, accountability was slow to follow. State prosecutors brought charges against 15 state and local officials. Seven pleaded guilty to misdemeanors in no-contest pleas. Just this year, the office of Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel announced that it was dropping the charges against the other eight officials. That decision caught Flint residents by surprise and local activists expressed dismay, but the attorney general’s office explained its decision as prompted by concerns with the quality of investigation conducted under the previous AG. That explanation, along with the search warrants issued for former Governor Rick Snyder’s cell phone the same month, has raised the possibility of charges against Snyder.

(Snyder has at least had to face professional consequences. After he was named a fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government in July, there was a swift backlash, citing his failures as governor during the Flint water crisis. A week later, Snyder announced that he would be “turning down” the fellowship.)

The Flint crisis made other water contamination crises harder, but still not impossible, to ignore. Newark, New Jersey, is now in the midst of what has been described in the New York Times as “the largest environmental crises in an American city in years.” As in Flint, acknowledgment of the problem was slow. After test results showed disturbing levels of lead in the city’s drinking water, Mayor Ras Baraka “mailed a brochure to all city residents assuring them that ‘the quality of water meets all federal and state standards’ … declared the water safe and then condemned, in capital letters on the city’s website, ‘outrageously false statements’ to the contrary,” according to reporting by the Times.

The difficulty in exposing problems of unsafe drinking water in large American cities is multiplied when those problems unfold inside prisons. And the vulnerability of city residents who must largely rely on officials’ assurances and the water flowing from their taps is compounded for incarcerated people with little or no access to bottled water.

In 2017, a report by Earth Island Journal and Truthout looked at the problems of toxic prisons, specifically the “connections between mass incarceration and environmental issues, that is, problems that arise when prisons are sited on or near toxic sites as well as when prisons themselves become sources of toxic contamination.” One of the primary problems, researchers found, was polluted drinking water.

At the Wallace Pack Unit in Texas, a prison that largely holds elderly and ailing people, a federal judge found in 2016 that people were forced to drink water with “impermissibly high levels of arsenic” and ordered the state to provide safe drinking water. That ruling came in response to an emergency motion as part of a 2014 class-action lawsuit over the state’s refusal to provide air conditioning.

The tainted water was all that was available to drink to cope with the unbearable heat. “The Texas Department of Criminal Justice’s solution during periods of extreme heat was to tell Pack Unit prisoners to simply drink more water, recommending up to two gallons of water a day on extremely hot days,” according to the 2017 report. “There was just one problem: The water at the Unit contained between two-and-a-half to four-and-a-half times the level of arsenic permitted by the EPA. Arsenic is a carcinogen. The prisoners drank thousands of gallons of the arsenic-tainted water for more than 10 years before a federal judge ordered TDCJ to truck in clean water for the prisoners last year.”