Pennsylvania Prisons Hired A Private Company To Intercept And Store Prisoners’ Mail

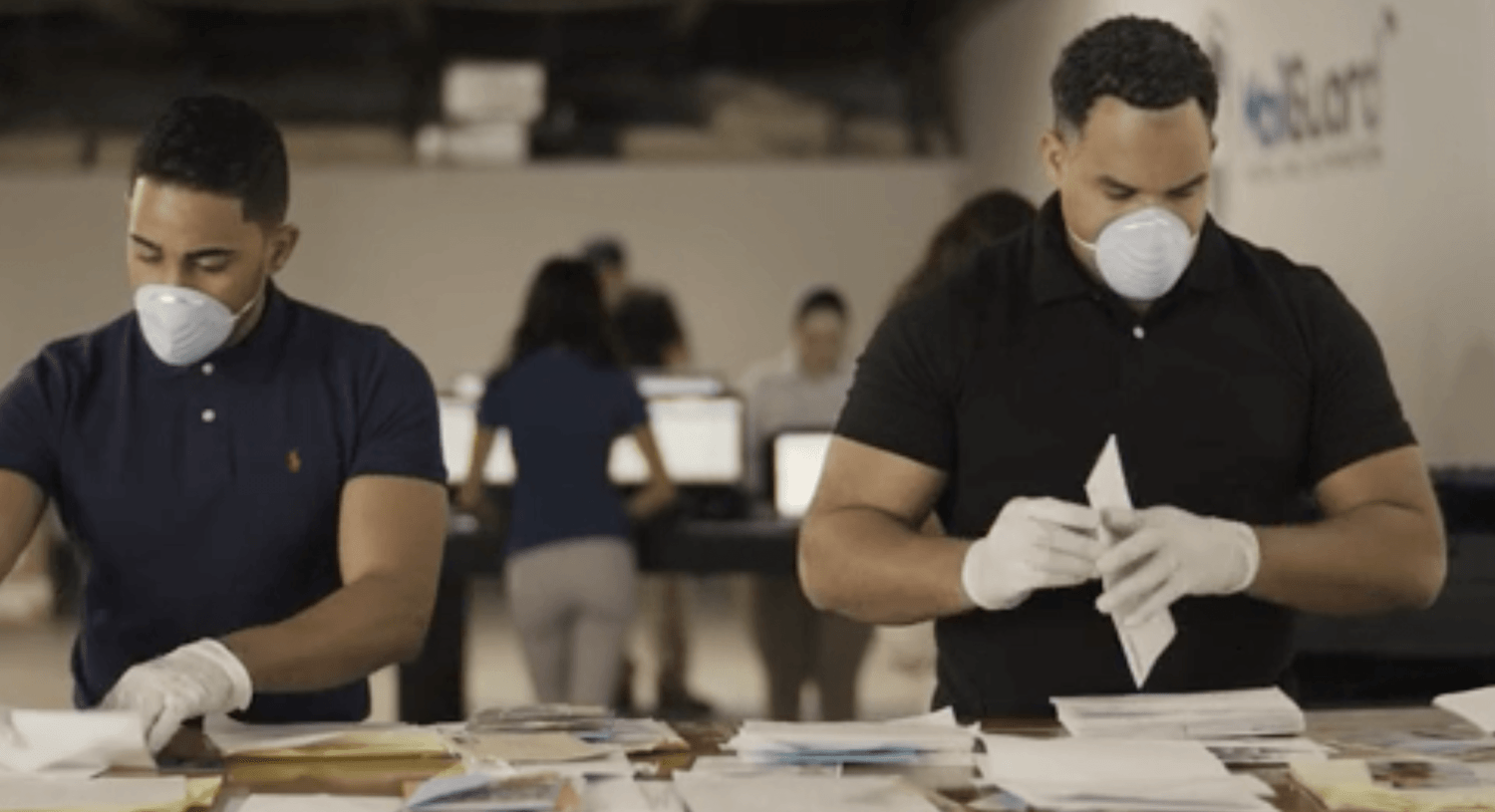

The company is being paid $4 million a year to open and scan prisoners’ mail into a searchable database.

A new policy has put Pennsylvania prisoners’ communications under intense surveillance in the name of stopping contraband drugs. On Sept. 5, the state’s Department of Corrections (DOC) announced that it would be largely restricting mail to prisoners. Effective immediately, all incoming mail would be sent to a private company in Florida, Smart Communications, for scanning into a searchable database. Prisoners would then receive photocopies of the incoming mail—and the originals would be shredded. The DOC has also banned prisoners from receiving books from vendors—including book donation organizations like Books Through Bars. Instead, prisoners will have the option of paying for ebooks via tablets that cost over $147 each.

The DOC implemented this policy after it said prison staff members were exposed to drugs. On Aug. 29, staff members at a Pennsylvania state prison were taken to the hospital because of alleged exposure to a substance that the DOC later identified as sorbitan trioleate, a chemical compound found in a wide range of household products. Later that day, the secretary of the DOC, John Wetzel, announced an immediate lockdown of the entire state prison system. The department’s press release stated that “multiple staff members [had] been sickened by unknown substances during the past few weeks.” The wide range of reported symptoms included elevated blood pressure, dizziness, migraines, and tingling extremities. One guard reported developing bumps along his hairline. When the lockdown was lifted on Sept. 10, the department stated that “toxicology results confirmed the presence of synthetic cannabinoid in multiple instances of staff exposure,” but did not specify which synthetic cannabinoid was found. “There are 30-40 types of synthetic cannabinoid and the field tests did not identify the type,” DOC spokesperson Amy Worden said in an email.

In two out of the 25 incidents where prison staff members received medical treatment since the beginning of August, field test results came back positive for synthetic cannabinoid, according to the DOC website. Worden also said the number of drugs found in the first eight months of 2018 (2,034 drug finds) have surpassed the amount found in 2017 (1,966 drug finds).

However, toxicology experts have poked holes in the official version of events, stating that simply touching K2 should not cause exposure to the drug. They have suggested that it might be “mass psychogenic illness,” where symptoms are similar to anxiety. The DOC has also not released any biological testing results, such as blood or urine tests, which would prove drug exposure.

A $15 million response

Despite the questions surrounding the alleged drug exposure, the DOC’s new security plans will cost Pennsylvanians $15 million, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer. The state is paying Smart Communications $4 million a year to scan and forward the mail, and will spend an additional $1.9 million annually on copy machines and paper to photocopy legal mail.

On its website, Smart Communications describes its MailGuard service as a “virtual mailroom” that digitizes all incoming mail and then feeds it into a database that contains “advanced security filters.” The company promotes the service by saying it will “dramatically improve intelligence capabilities” and “eliminate the last form of undocumented, uncontrolled communication.” Smart Communications did not share its MailGuard privacy policy, but the DOC said the company would retain copies of mail in its database for seven years.

Mark (not his real name), a person currently incarcerated in the Pennsylvania state prison system, said in a letter to a prisoner rights advocacy group that he thinks “the real reason [for the policy change] is to further monetize incarceration,” adding that “this policy has effectively precluded prisoners from obtaining knowledge.”

The Abolitionist Law Center says it has received complaints from prisoners and their families that include privacy concerns with an outside corporation having access to all their mail, accounts of the photocopies being unreadable or incomplete, and color photographs being photocopied in black and white (Worden said the DOC is in the process of installing color printers in all their facilities). “It’s one thing to know strangers are perusing through the most intimate details of your life and it’s completely jarring to now know that a whole corporation is copying the information,” Bret Grote, legal director of the center, said.

This additional layer may also add more room for error and confusion.

“We had one report of outgoing mail being wrongly sent to Florida where it was copied and returned to the incarcerated sender instead of the addressee,” Grote said. “We have no confidence that similar mistakes will not continue to occur.”

Sean Damon, a paralegal and organizer with the Amistad Law Project, said the new policy will most likely result in self-censorship. Some prisoners have asked loved ones not to send them mail, multiple organizers said. “An incarcerated person may not want a private company to know about them and their family’s medical problems. They may not want a private company to know about grievances that they have,” Damon said.

“The real thing that is frightening to me is not only the overreach by the government but the self-censorship that it’s going to entail and the chilling effect that’s currently happening on family members and their loved ones.”

Legal mail endangered

The new policy of photocopying legal mail has effectively ended mailed communication between lawyers and their clients because they cannot guarantee confidentiality. The prison retains the original copy of the mail for 15 days.

Several legal assistance groups have instructed their attorneys to stop sending mail to their clients immediately.

“This new policy is already having a chilling effect on how lawyers are communicating with their clients. Because legal mail is being opened and copied, attorney-client privilege is basically being ignored,” Grote said. “This jeopardizes the ability to zealously advocate for clients because there is a possibility that any strategy and evidence communicated in legal mail is compromised.”

The Abolitionist Law Center, the ACLU of Pennsylvania, and the Pennsylvania Institutional Law Project wrote a letter to the Department of Corrections last week that stated: “Experts in professional ethics have advised us that the DOC’s new process for handling legal mail raises sufficient confidentiality concerns that we should not continue to communicate privileged information with clients incarcerated in state prisons via mail.”

Worden argued that the new policy is more secure than how they previously treated legal mail.

“The procedure for processing privileged mail is more confidential than the prior policy,” Worden said. “Staff no longer are required to inspect each page for the presence of contraband, significantly reducing the time that staff handle or view privileged documents and allowing the inmate to receive the mail sooner. Finally, under the revised procedure, the entire transaction is recorded by video.”

An end to book donations

The policy also bans educational programs and books donation programs. Instead, the DOC has said that prisoners will have access to free books at the library and e-books (which cost $3 to $25) on $147 tablets. The DOC has also announced that prisoners can request a book through the department and pay for it via a cash slip. If it approves the request, the DOC will then order the book and have it shipped to the prisoner.

Books Through Bars, a donation service that has operated in Pennsylvania for over 30 years, is protesting this change as censorship. Through the program, prisoners can request two or three free books every three months.

“Its direct effect is going to be cruelty. It surveils and censors and monitors people’s reading choices.” Keir Neuringer, a longtime volunteer with Books Through Bars, said. “We believe books are not contraband. Knowledge is not contraband. And that policy makers who align themselves with the action of taking books out of people’s hands are putting themselves in historical precedent that is very frightening.”

Many organizers agree that the book donation ban is an increase in prison censorship as well as surveillance. A “million books are published a year. The DOC is saying they’ll offer [about] 8,000 titles on e-readers,” Neuringer said. “When you consider that those of us on the outside have access to millions and millions of titles. This policy cuts you out of such an enormous access to books.” Neuringer also stated that e-book tablets make it possible for the DOC to start monitoring what people were reading.

Robert “Saleem” Holbrook, who was incarcerated in the Pennsylvania prison system for 27 years, said most prisoners have access to the library, at least once a week. But the library does not have a large variety of books. “Prisoners who want a broader read or greater depth of reading unfortunately are left out of books at library.” Holbrook, an organizer with the Abolitionist Center, said. “They’re mostly oriented towards fiction, not nonfiction.”

“We are effectively being prevented from learning, making connections to and communicating with the outside world,” Mark said.