A Rarely Used Power Could Free Prisoners in Pennsylvania. But the Governor Is Not Using It.

The Office of General Counsel determined that the governor could likely use reprieves to release vulnerable people from prison to control COVID-19’s spread, but the office is advising against it, according to internal emails obtained by The Appeal.

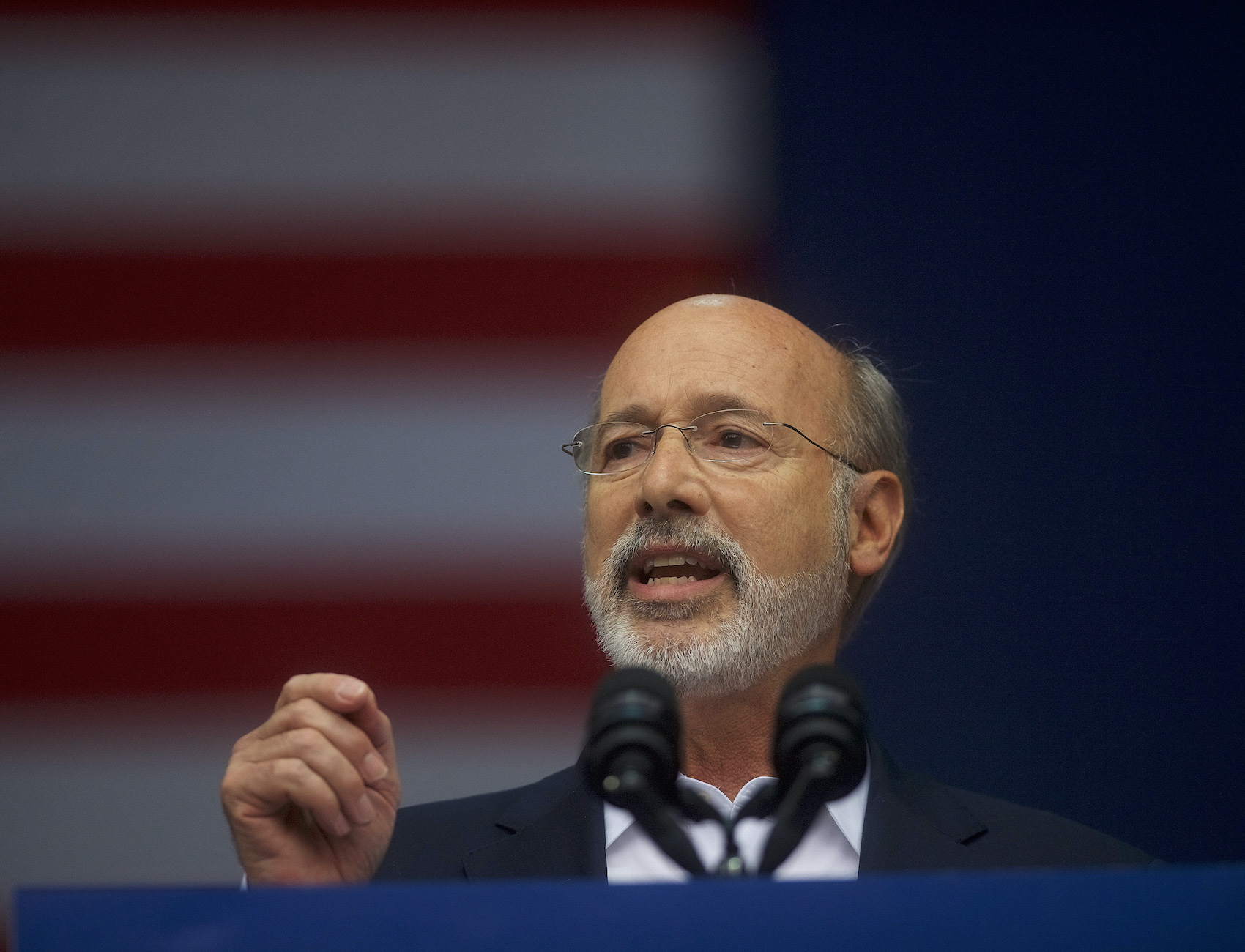

Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf most likely has the ability to remove thousands of the most vulnerable people from state prison with the stroke of his pen as COVID-19 spreads across the state. But he is not using that authority.

In an email obtained by The Appeal and sent to a spokesperson at the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections (DOC), Anne Cornick, deputy general counsel for the state Office of General Counsel, said the agency reviewed whether Wolf has the authority to issue reprieves—temporary suspensions of prison sentences. The office, which advises the governor and other executive agencies on legal matters, determined that Wolf “could probably do it,” Cornick wrote, but “it was not the preference” to use the reprieve power.

The email was part of an internal discussion about how to respond to questions from The Appeal regarding Wolf’s ability to grant reprieves. Cornick directed the DOC spokesperson to avoid discussing the option in its response. “I think we want to give an answer that doesn’t answer directly the reprieve questions,” Cornick wrote.

Neither Cornick nor the governor’s office responded to a request for comment. The DOC did not respond to a request for comment, but lawyers for the department asserted that the emails obtained by The Appeal were covered under attorney-client privilege.

Reprieves are a form of clemency, but they do not go as far as commutations, which permanently reduce a criminal sentence, and pardons, which absolve a person of criminal wrongdoing.

Although Wolf has previously used reprieves to delay executions, Ben Notterman, a research fellow at New York University’s Center on the Administration of Criminal Law, told The Appeal that the power is much more expansive and largely unchecked in Pennsylvania.

“I’m sure there are logistical and public health-related considerations about the manner in which we remove people, but there don’t seem to be any legal (or moral) ones,” Notterman said in an email. “And it should be done immediately, while we are still able to limit COVID-19’s spread.”

The state Constitution gives the governor the sole authority to grant reprieves, commutations, and pardons. However, the governor must receive approval from the state Board of Pardons before issuing commutations or pardons.

This restriction is not placed on reprieves.

“The current COVID-19 crisis illustrates precisely why reprieves—unlike pardons and commutations—are free from regulation: the governor needs a mechanism to act immediately to avoid disaster in prisons/jails, whether the disaster is putting a potentially innocent person to death or stemming a viral outbreak that could lead to many deaths,” Notterman said.

NYU law professor Rachel Barkow, an expert on clemency in the United States, agrees with Notterman’s assessment. Barkow recently called on governors across the country to use their executive authority to remove people from prisons and jails to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

While officials across the country have begun to release people from jails during the pandemic, they have moved more slowly to release state prisoners. Jails typically have more options to release those held in custody. In Pennsylvania, judges can usually grant early release for most people sentenced to jail time, or they can reduce or choose not to impose bail requirements.

State prisons generally have fewer mechanisms for early release. In Pennsylvania, parole must be approved by the parole board, the compassionate release program is restrictive, and there is no furlough program for people in prison.

On Monday, the DOC announced that all incarcerated people would be put under quarantine as a precaution, a day after the agency said a man being held at State Correctional Institution Phoenix in Montgomery County had tested positive for COVID-19. He is the first incarcerated person in a Pennsylvania prison to test positive for the disease.

Prisons and jails historically have been a hub for the spread of communicable diseases. A lack of access to personal hygiene supplies, an inability to isolate or socially distance, and typically substandard medical care tend to allow for the proliferation of disease. For example, the rate of tuberculosis in prisons is nearly twice that of the general population, according to a study published in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society.

New York City’s Rikers Island jail complex has already seen rapid growth in COVID-19 infections. As of Monday, 167 people on Rikers Island had tested positive for the disease, a figure that is doubling roughly every two days.

Bret Grote, legal director for the Abolitionist Law Center, said the U.S. needs to begin releasing people in prison to halt the spread of the disease. More than 20,000 people are already released from Pennsylvania prisons every year, he said, “and if political will is to be commensurate to the magnitude of the looming crisis, at least 10,000 can be safely released in an expedited fashion to relieve the burden on the system and limit transmission of COVID-19 inside the prison and among the broader community.”

There are currently more than 45,000 people held in state prisons in Pennsylvania. As of last week, the DOC had only four ventilators to serve that entire population.

As of the end of 2018, more than 10,000 people being held in a state prison were 50 years old or older. According to the University of Oxford, people over 50 are at least four times more likely to die if they test positive for COVID-19 than people under 50.

“Political cowardice must not allow our people behind the walls to become a sacrifice population,” Grote said.