Solitary is a ‘Tomb’ With No Escape, Virginia Prisoners Allege

A new lawsuit, filed against the Virginia Department of Corrections, says prisoners are kept in isolation for frivolous reasons and prevented from rejoining the general population.

Prisoners in two Virginia facilities were held for years in almost complete isolation with virtually no way out, according to a class action lawsuit filed today by the ACLU of Virginia and law firm White & Case LLP. The suit alleges that the state Department of Corrections and several department employees abused the use of solitary confinement at Red Onion and Wallens Ridge state prisons.

The department’s Segregation Reduction Step-Down Program, which is supposed to provide a pathway back to the general population, can, in practice, trap people in solitary confinement, according to the suit.

“The current Step-Down Program is a system of vague standards, contradictory goals, and malleable jargon used to conceal what is nothing more than an indefinite or permanent solitary confinement regime,” it states.

The suit was filed on behalf of 12 named plaintiffs, along with others previously or currently in isolation, and those who could be held in solitary in the future at the two prisons. The exact number of people in solitary confinement is difficult to determine because of a lack of transparency on the part of the Department of Corrections, according to the ACLU of Virginia.

Those in solitary confinement are in 8-by-10 foot cells for more than 22 hours per day, according to the suit. Each cell has two windows: one on the steel door and one, which is covered in a white film, facing the outside, the ACLU’s suit states. Food is provided through a slot in the door. Even during recreation, prisoners remain isolated in an empty cage in the prison yard, according to the complaint.

Once someone is placed in solitary, it can be a Sisyphean struggle to escape, according to the complaint. The Department of Corrections’s step-down program requires prisoners to complete several requirements that can take 15 to 30 months, according to the suit. Prisoners, for instance, are asked to fill in the blanks in workbooks, the suit states, and are continually evaluated on their hygiene, the neatness of their cells, and their “rapport with staff and other prisoners.”

People have been kept in isolation in Red Onion and Wallens Ridge for minor violations such as not shaving their beards or use of “insolent language,” according to the complaint. If a prisoner is found to be deficient in any way, he can be made to restart the program, according to the suit.

We don’t believe their use of solitary confinement, whatever they want to call it, meets constitutional standards.

Vishal Agraharkar ACLU of Virginia

In a statement emailed to The Appeal, Department of Corrections spokesperson Lisa Kinney wrote that as of April 30, there are 45 people in “long-term restrictive housing” at Red Onion State Prison and none in housed at Wallens Ridge State Prison or anywhere else in the Virginia prison system.

“The Virginia Department of Corrections does not have ‘solitary confinement’ by the Virginia ACLU’s own definition,” she wrote.

“The ACLU’s definition of solitary appears to involve an inmate being held in a cell at least 22 hours a day with little to no interaction with other people and little to no stimulation,” she wrote in a follow-up email. “That’s not the case for any offender in Virginia,” she wrote.

But Vishal Agraharkar, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU of Virginia, disputed her assertion. “They say this is restrictive housing and there is no such thing as solitary confinement, but that’s not accurate,” he told The Appeal. “We don’t believe their use of solitary confinement, whatever they want to call it, meets constitutional standards.”

Daniel Greenfield, the solitary confinement appellate litigation fellow at the Roderick & Solange MacArthur Justice Center, is litigating a suit against the Department of Corrections on behalf of Alfonza Greenhill, who has been in solitary at Red Onion since 2013, according to Greenfield. He was sent there just days after entering the prison for “disobeying a direct order,” according to Greenfield’s brief.

“In my experience, prisoners in solitary confinement in Virginia, including at Red Onion, are almost wholly isolated from other human beings for upwards of 23 hours a day and what little interaction they do have with other human beings cannot be characterized as meaningful with a straight face,” Greenfield said. “They live the vast majority of their lives in a tiny cell with limited access to diversions.”

Beginning in 2017, the Vera Institute of Justice partnered with the Virginia Department of Corrections in an initiative to reduce the use of solitary confinement. According to Vera’s report, there were 870 people “in some form of restrictive housing” at the end of July 2018. When asked about those numbers, Kinney said Vera included people in both short-term and long-term restricted housing.

Obtaining data from the Department of Corrections about its use of solitary has been a constant battle, said Agraharkar. Earlier this year, Governor Ralph Northam signed legislation that will require the Department of Corrections to publicly report on the practice.

He would say, ‘I don’t have nothing in here.’ … He’s living in a tomb.

Kimberly Jenkins-Snodgrass Interfaith Action for Human Rights

The class action lawsuit is the latest condemnation of solitary confinement in Virginia. Conditions at Red Onion were the subject of the 2016 HBO documentary, “Solitary: Inside Red Onion State Prison.”

Last September, the ACLU of Virginia and the MacArthur Justice Center sued officials with the state Department of Corrections on behalf of Nicolas Reyes, who they say has been held in solitary confinement at Red Onion for more than a dozen years.

“At times he has been unable even to identify the prison where he is held,” according to the complaint. “He experiences routine, vivid hallucinations, in which he communicates with his dead parents.” The Department of Corrections said at the time that it could not comment on pending litigation, but that it did not use solitary confinement. It reportedly said that the Segregation Step-Down Program has cut the number of prisoners in long-term restrictive housing at Red Onion from more than 500 in 2011 to fewer than 100 last fall.

The plaintiffs in today’s suit have, like Reyes, suffered severe harm from living in isolation for years, according to the ACLU. One prisoner, who has schizophrenia, lost 75 pounds during his more than four years in solitary confinement at Red Onion, according to the suit.

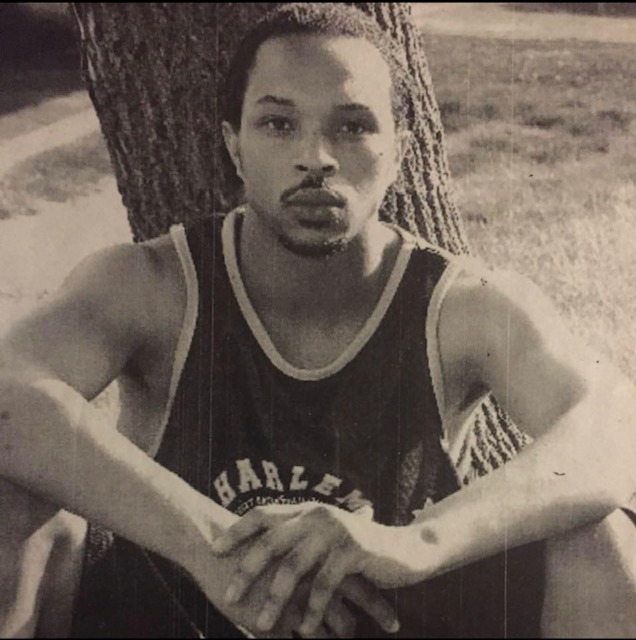

Kimberly Jenkins-Snodgrass, vice chairperson for Interfaith Action for Human Rights, could see the toll approximately four years of solitary confinement at Red Onion took on her son, Kevin Snodgrass, who was convicted of murder and is scheduled to be released in 2053. Jenkins-Snodgrass claims her son was wrongfully convicted.

She and her husband regularly made the six-hour drive to the prison for a one-hour visit. They were not allowed to touch their son and spoke to him by phone, separated by a plexiglass partition.

“He would say, ‘I don’t have nothing in here,’” she said. “He’s living in a tomb.”

On Nov. 25, 2017, after Snodgrass was released from solitary confinement, Jenkins-Snodgrass hugged her son for the first time in four years. He shivered in her arms, she said.

“He hadn’t been touched in all those years,” she said. “Imagine going four years and nobody shake your hand, hug you, or breathe on you.”

Even though her son is out of solitary confinement, she remains committed to speaking out for those left behind.

“That’s what I promised my god,” she said. “If you would give him grace and free him, I’ll go back and get the others.”