My Friend Spent Much of His Formative Years in Prison. He Didn’t Have to Die There.

Josh Norman was one of the 17 people to die in Mississippi prisons so far this year. His death raises important questions about the state’s failures.

This piece is a commentary, part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis on important issues and actors in the criminal legal system.

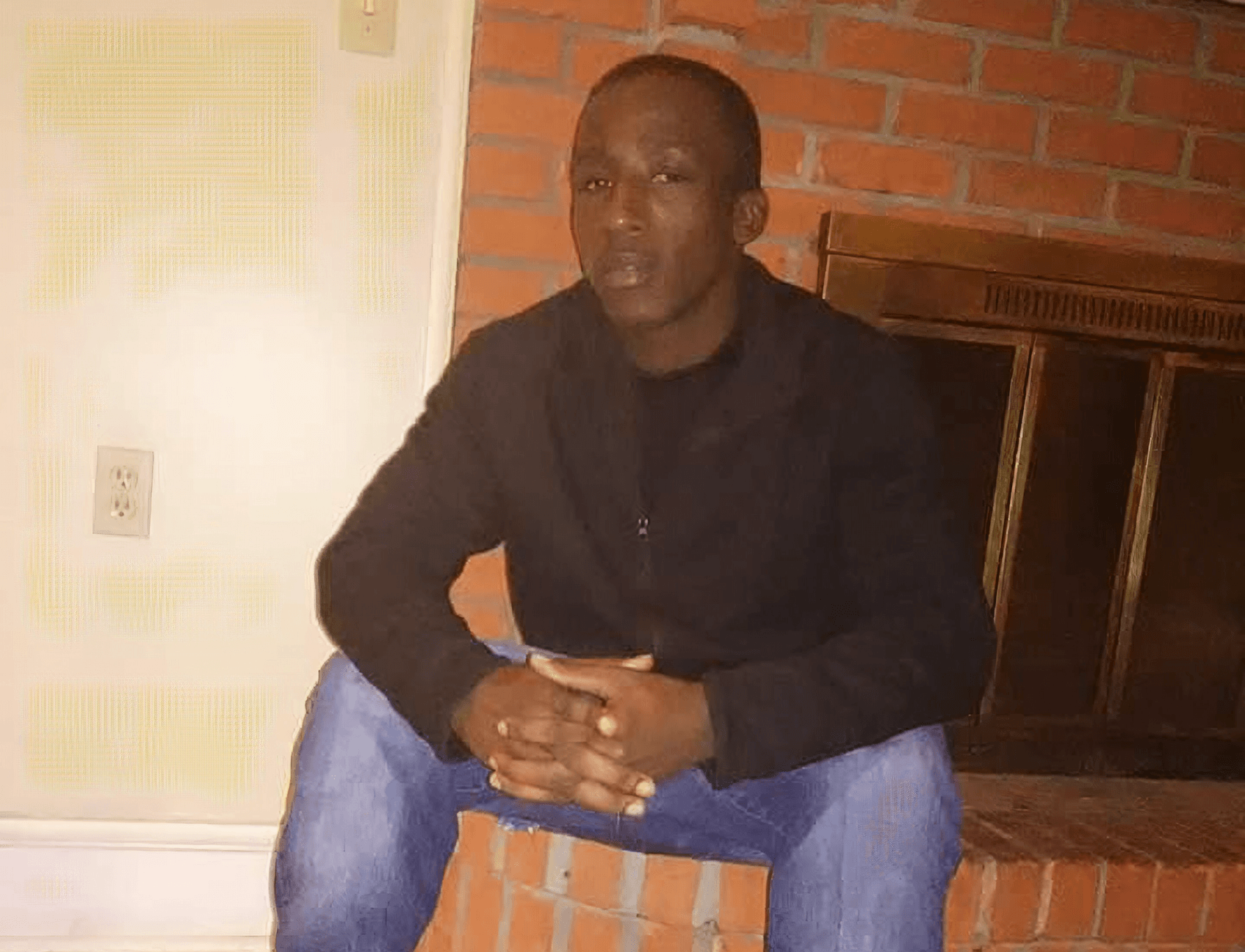

While the world mourned Kobe Bryant last month, there was another reason basketball haunted my thoughts. I learned that my childhood friend, Josh Norman, was found hanging in his cell in a Mississippi prison. He was only 26. As a kid, I would play pick-up basketball at Josh’s house until the streetlights came on. He will forever be the “big kid” my 10-year-old self looks up to.

Josh’s name is the eleventh on a troubling list of people who died in Mississippi’s prison system this year. Seventeen have died so far, 10 of them at Parchman, where Josh was held in unsafe conditions in Unit 29. His death should make the state of Mississippi reflect on how its shortcomings affect the lives of incarcerated citizens.

He had one of the best basketball hoops in the neighborhood—a crisp white net with a wooden backboard and an NBA model rim—and his house was a routine after-school meeting spot for the neighborhood kids. On the court, Josh was a fierce competitor who also valued fairness. He was somehow both tenacious and compassionate, a leadership style that distinguished him from most players.

The last time I saw Josh was in 2009. At only 17 years old, he was sentenced to eight years for an armed robbery. His indictment alleges he threatened to rob someone with a beer bottle at age 14. The circuit court records indicate his lawyer asked the court to transfer his case to youth court. If he had been prosecuted in youth court, he most likely would not have been punished so severely, and would have been held in better conditions at a safer facility. But the case wasn’t transferred, and he was sent to an adult prison.

Josh spent much of his formative years in the custody of the state of Mississippi. The Department of Corrections controlled where he lived, what he did, and who he was around. When he was released after serving close to eight years, in April 2018, he wasn’t prepared for life outside of that system.

One of the Mississippi Department of Corrections’ stated goals is to “meet offenders’ reintegration efforts through rehabilitation and support programs.” This means Josh should have been offered counseling services and educational or vocational opportunities, placed in behavioral support groups, and provided relevant drug and alcohol treatment. He should have been offered re-entry services and programs to help him transition back into society. Instead, the state provided him with shamefully little support.

These kinds of programs can significantly reduce recidivism, as Rachel Elise Barkow explains in her book “Prisoners of Politics: Breaking the Cycle of Mass Incarceration.” Studies suggest that well-designed cognitive-behavioral therapy programs could reduce recidivism by more than 50 percent. A re-entry program run by the Minnesota Department of Corrections was found to reduce reincarceration by 36 percent over a 12-month period, Barkow writes, and participants were 13 percent more likely to secure employment within a year of release than nonparticipants.

During Josh’s incarceration, Mississippi’s corrections budget was regularly and repeatedly cut. The prisons were overcrowded, unsafe, and understaffed. There was less prison programming, less drug and alcohol treatment, and fewer re-entry services.

Less than 10 months after his release, Josh was arrested for armed robbery and burglary of a dwelling. He was accused of breaking into a woman’s house and robbing her with a gun. If the allegations are true, of course, he bears personal responsibility for his actions. But we need to ask ourselves about the the prison system—how it shaped Josh as he became an adult and the role it had in producing this outcome.

With a lack of rehabilitative prison programming and re-entry assistance, the state of Mississippi failed Josh, and it failed the most recent robbery victim, too.

Josh made mistakes, but none of us should be judged by our worst actions alone.

His death shows that we need significant budget increases for rehabilitative programming. Judges, though given much discretion, should be more merciful in their sentencing, especially for minors. No one should be held in the conditions Josh was held in at Unit 29—where there were complaints of roaches, rats, and black mold, and many cells went without water and power.

Unfortunately, Josh’s story is not unique, and his death is not either. Let’s honor Josh. Let’s right our wrongs, Mississippi.

Justin Brooks is a second-year student at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law.