For Many Serving Harsh Sentences, the Governor Becomes a Last Hope

Lawmakers are recognizing the harms of mass incarceration. But some governors are reluctant to use their clemency power to address them.

The prosecutor, the judge, and Carrie Wilson’s lawyer were all in agreement: She should serve 15 years in prison. But a restrictive law on the books in Oregon forced the judge to sentence her to life, with a minimum of 25 years to serve.

On May 11, 1996, an acquaintance named Billy Ray Bostic told Wilson to drive him to get more drugs, according to her commutation application. She felt intimidated by Bostic and agreed. According to her application, she knew he had a gun and planned to commit a robbery.

When they pulled up to Ellisar Juariz Valladares’s apartment in Salem, Bostic took the gun and went inside while Wilson stayed in the car, according to a sentencing memo. At the time, Wilson told The Appeal, she was “an alcoholic, doing drugs.”

As she waited for Bostic to return, police officers approached her truck and asked her to go to the station with them, according to the sentencing memo. Initially, she lied about who she was waiting for, but then admitted it was Bostic. She told the police she had lied because she was scared of Bostic, according to the memo. Bostic was convicted of murder and sentenced to life.

On Nov. 20, 1997, Wilson, then 33, pleaded guilty to robbery and felony murder. Felony murder laws require lengthy sentences for people with tangential involvement in the crime—such as lookouts or passengers in getaway cars—even if they were unaware of any plans to commit murder or did not know a murder had occurred. Some states, including Massachusetts, have reformed the statute.

The judge and the prosecutor thought life in prison was too harsh a punishment. But three years earlier, Oregon voters had passed Measure 11, also known as “One Strike, You’re Out,” which subjected various offenses, including felony murder, to mandatory minimum sentences.

There was one way she could serve what they considered a fair sentence proportional to her involvement in the crime. Her sentence could be reduced through a gubernatorial commutation, the judge said before accepting her plea, but “it’s a long shot.”

“You need to understand the governor doesn’t do it very often, OK?” the judge told Wilson.

The prosecutor agreed to support her application after 15 years, if she “behave[d]” while incarcerated, according to the court transcript.

Over the years, two governors—Ted Kulongoski in 2010 and John Kitzhaber in 2015—did not review her application. In 2018, Wilson submitted a third application. In a letter to Governor Kate Brown, dated Oct. 7, 2018, the judge wrote that she and the prosecuting attorney believe Wilson’s application should be granted.

“We have supported her requests to two prior governors who did not take the time to consider her request,” wrote retired Judge Pamela Abernethy. “I hope that you will be the one to do so.”

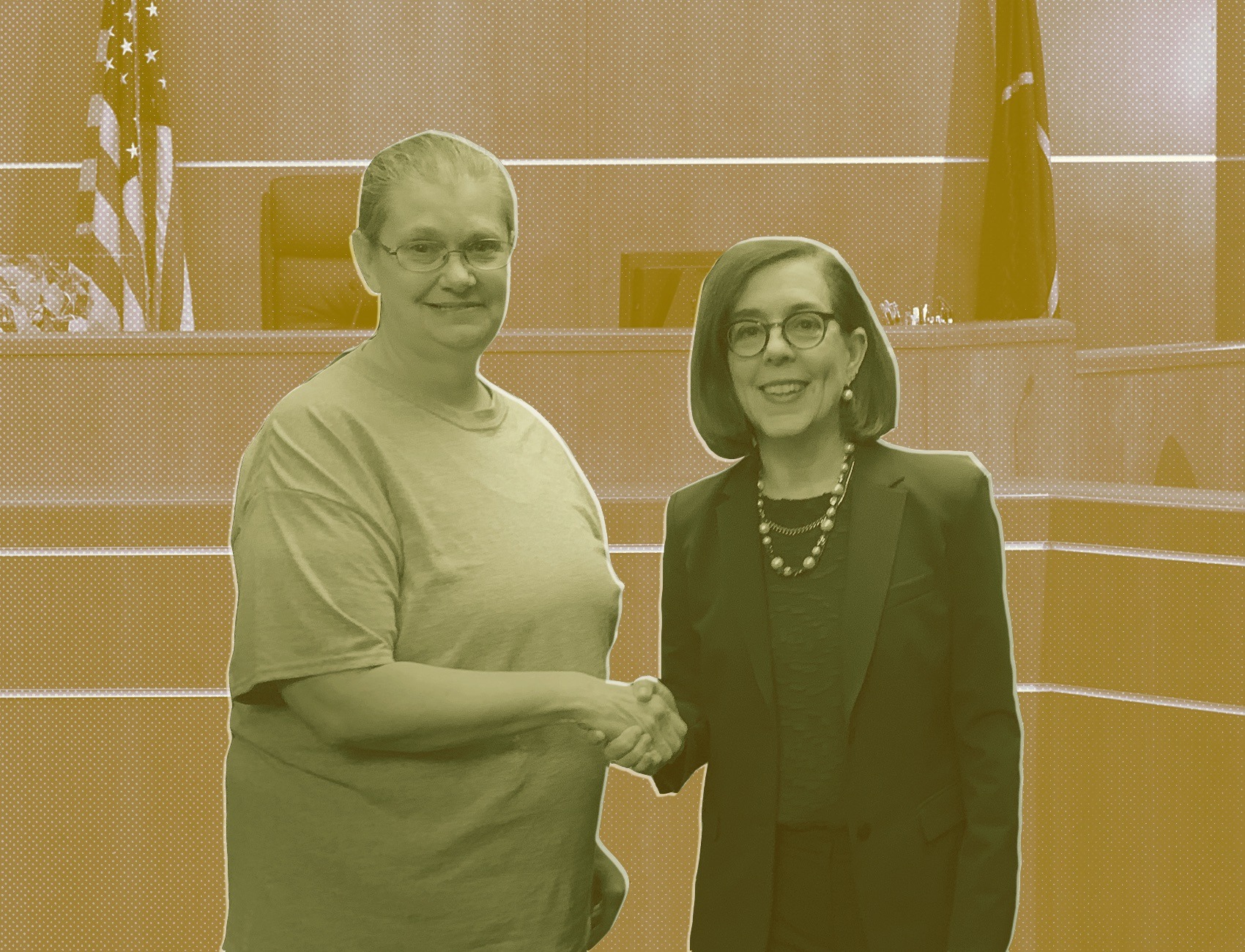

Finally, after Wilson served about 23 years in prison, Brown commuted her sentence. Last month, Wilson, now 55 and a grandmother, was released.

“I’m very, very grateful to Governor Brown for giving me this opportunity, to believe I can do this. And I want to make her proud,” Wilson said before her release in a telephone interview with The Appeal from Coffee Creek Correctional Facility. “I just will be indebted and grateful to her for life, for the life she’s giving back to me.”

But there are still many others with similar stories who remain behind bars. Across the country, as lawmakers recognize the harms of mass incarceration and push for legislative reforms, commutations are another way to reduce the prison population, said Rachel Barkow, a law professor at New York University and author of “Prisoners of Politics: Breaking the Cycle of Mass Incarceration.” But governors are often reticent to use their commutation power, she said.

“It should be a regular part of their job to correct mistakes in the criminal justice system, to remedy excessive sentences, to recognize when people have been rehabilitated,” Barkow said. “We have thousands of people serving sentences that are just excessive both given what they did and given the kinds of people they are today.”

In 1994, before Measure 11 was enacted, there were approximately 6,000 people incarcerated in Oregon. As of February 2019, the population had more than doubled—largely because of the measure, criminal justice reform advocates say.

Brown has championed efforts to reform Measure 11. Last July, she signed into law Senate Bill 1008, which will require second-look hearings for those who have served 15 years for offenses that occurred when they were under 18. SB 1008 also bans juvenile life without the possibility of parole and requires that a judiciary hearing be held before a minor is transferred to adult court. Measure 11 mandated the transfer of children 15 and older to adult court for a number of offenses.

But less is being done for the people who are already incarcerated and serving lengthy sentences because of Measure 11. SB 1008, for instance, does not apply retroactively. Only those sentenced after the law took effect on Jan. 1 will benefit.

And Brown, who took office in February 2015, has granted relatively few pardons and commutations. Between July 1, 2015, and Feb. 14, 2020, Brown received 457 applications for executive clemency, which includes pardons, reprieves, remissions, and commutations, according to the governor’s office. Brown granted 20 pardons, approved six conditional commutations, and denied 240 commutation applications, according to the governor’s office. Three commutation applications were closed because the applicant died. The governor’s office declined The Appeal’s request for an interview.

In an interview with Willamette Week last year, she said, “I have used my clemency and pardon tool very judiciously.”

Kitzhaber, Brown’s predecessor who was also a Democrat, granted little relief to Oregon’s prisoners. He approved eight commutations and two pardons during his approximately 12-year tenure, according to Lewis & Clark Law School professor Aliza Kaplan’s journal article “The Governor’s Clemency Power,” co-authored with Oregon attorney Venetia Mayhew. Kaplan is the director of the Lewis & Clark criminal justice reform clinic, which represents Wilson.

“Governors shouldn’t be afraid to use this,” Kaplan told The Appeal. “Governors should embrace their clemency power as a way to fight injustice.”

Suzanne Miles is among those still waiting for justice, her legal advocates say. As a child, she was psychologically and physically abused by family members, according to her commutation application. Her homes as an adult were no better.

At 19, she met the father of her first child. During their relationship, according to her application, he choked and slapped her, and often forbade her from leaving their home. In 1983, less than a month after she gave birth to their daughter, she left him. The father of her second child—whom she began a relationship with in 1985—beat her and went into “drunken rampages,” according to the application. After their daughter was born, she left him as well.

In 1993, she met Matt Miles and they married in 1995. As with her previous relationships, he psychologically and physically abused her, according to her application.

“Being in situations of domestic violence, it’s like a roller coaster,” Miles, another Lewis & Clark client, told The Appeal in a phone call from Coffee Creek Correctional Facility. “I feel like I have learned more about myself while I’m in prison to know that I’m valuable in so many different ways that I would never allow somebody to treat me like that again. It’s a horrible way to have to learn that lesson.”

On Feb. 28, 2000, she bought a gun to kill herself, according to the application. Miles, who was suffering from depression, had begun taking the antidepressant Paxil, which her lawyers say contributed to her suicidal ideation and violent behavior.

The next day, Miles’s husband told her he wanted a divorce. She drove to his office. While he sat at his desk, she shot him. She then tried to kill herself, but the gun jammed. She shot him a second time, then drove to the police station and confessed, according to her application.

In 2002, Miles was convicted of murder and sentenced to 25 years to life. She volunteers in the hospice unit and trains service dogs to work with people with disabilities, according to the state Department of Corrections. She has never received a disciplinary infraction, according to the department.

“I agonize over the choices that I made, that I’ve taken Matt’s life and hurt my children,” said Miles, now 57. “That’s something that I wish I could change so I just try to be a better person every day because I don’t ever want to be a victim again and I don’t ever want to victimize anybody ever again.”

In another application before Brown, attorney Mayhew told the story of Jerome Sloan: After his mother kicked him out when he was 13, he was homeless for much of his teenage years. In 1994, at 19, Sloan was sentenced to life without parole for the murder of Roger Penn who was killed during a robbery. Sloan has accused his co-defendant Robert Kelley of shooting Penn, and Kelley has accused Sloan of shooting Penn.

Now 45, Sloan leads classes on restorative justice and conflict resolution. “Most of my work here is based around helping young gang members turn their life around,” he wrote to Brown. “I can connect with those young men easier than most because I used to be just like them: a misguided, angry, miserable young adult.”

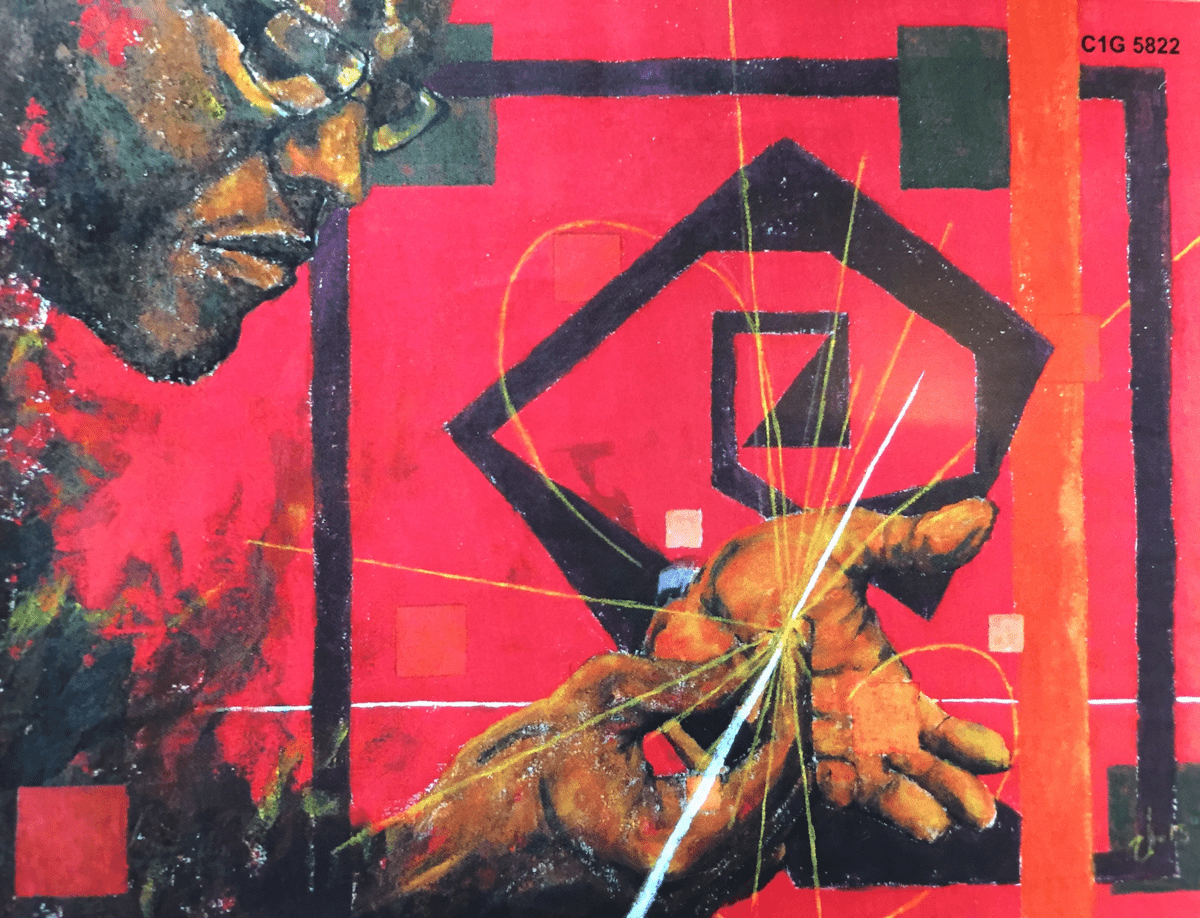

Sloan, a painter, has also taught art classes to fellow prisoners, according to the Department of Corrections. Art, he wrote to Governor Brown, “changed my life and I want to use it to help change others.”

In 2016, he met Penn’s son, David Penn, who supports Sloan’s application requesting that Brown commute his sentence to life with parole.

“Jerome clearly has worked hard to become a better man which is what should define him,” Penn wrote in a letter to Brown, included in Sloan’s application. “For Jerome to be able to take all that he has learned and who he has become, due in part to my father’s murder, and turn it to good, that would bring meaning to it.”