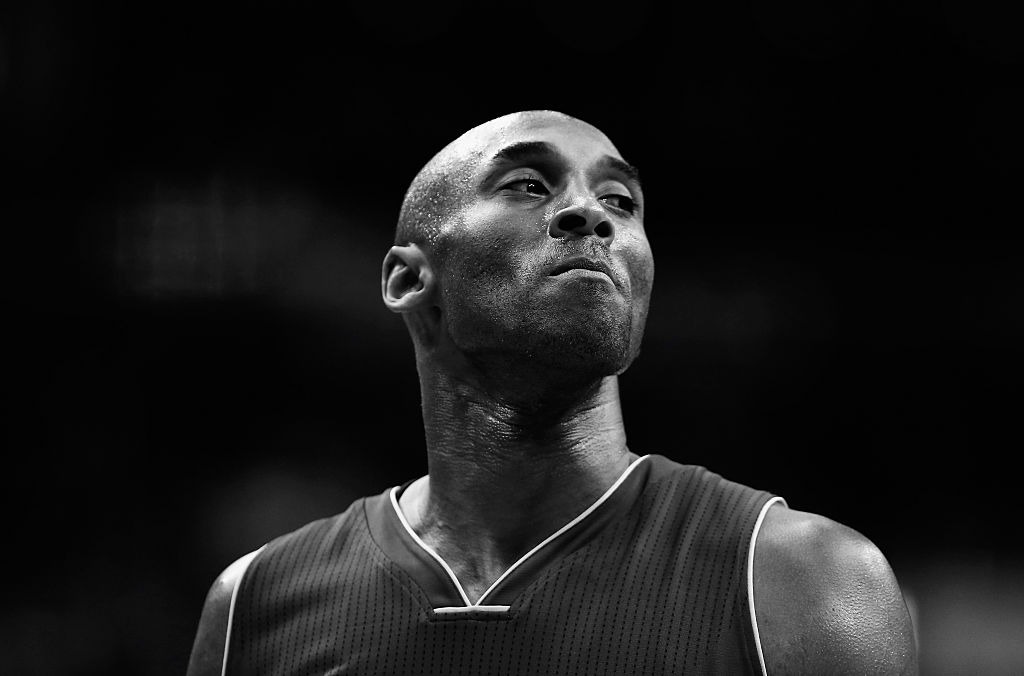

On Kobe Bryant, The Search For Nuance In An All-Or-Nothing System

On Sunday, news that basketball legend Kobe Bryant had died in a helicopter crash along with his daughter and seven others overtook the impeachment trial as the top news story. “A generation lost a hero on Sunday, thousands of basketball players who grew up spinning along baselines and firing up picture-perfect midrange jump shots lost […]

|

On Sunday, news that basketball legend Kobe Bryant had died in a helicopter crash along with his daughter and seven others overtook the impeachment trial as the top news story. “A generation lost a hero on Sunday, thousands of basketball players who grew up spinning along baselines and firing up picture-perfect midrange jump shots lost the legend that showed them how,” wrote Chris Mannix for Sports Illustrated. “There are no words for such an unspeakable tragedy.” Josh Levin, of Slate, noted that ESPN’s coverage stuck to Kobe’s professional achievements and ABC News’s special report was “extremely hagiographic.” But another portrayal of Bryant soon emerged, one that was difficult for many to reconcile with the first: as a man credibly accused of a serious sexual assault. In 2003, Bryant was arrested and charged with felony sexual assault after a complaint by a 19-year-old hotel employee in Colorado. The charge was later dropped when it became clear that the accuser would no longer testify against him, and Bryant settled a civil suit with her out of court. She informed the court one week before opening statements were to be made that she would not testify after having been “dragged through the mud for months by the media and Bryant’s defense team,” as one news outlet described it. In the hours after the news broke of Bryant’s death, amid the flood of public tributes, Washington Post reporter Felicia Sonmez posted, without comment, a link to a 2016 Daily Beast article that detailed the 2003 allegations against Bryant and the hurdles faced by his accuser. The New York Times reported that Sonmez’s tweet “stood out in the general outpouring of appreciation for Bryant” and “drew a swift backlash.” She commented on the backlash, writing on Twitter: “Well, THAT was eye-opening. To the 10,000 people (literally) who have commented and emailed me with abuse and death threats, please take a moment and read the story—which was written (more than three) years ago, and not by me.” Sonmez also posted what appeared to be a screenshot of an email she had received that used offensive language and called her a lewd name. The image displayed the sender’s full name. The Washington Post then suspended Sonmez, saying that her tweets “displayed poor judgment that undermined the work of her colleagues.” The issue is charged, to put it mildly. There seem to be some, on both sides, who believe there is no room to acknowledge the other. But the possibility that two truths can coexist is exactly what Bryant alluded to in the written apology he issued as part of the settlement to his criminal case: “Although I truly believe this encounter between us was consensual, I recognize now that she did not and does not view this incident the same way I did. After months of reviewing discovery, listening to her attorney, and even her testimony in person, I now understand how she feels that she did not consent to this encounter.” Some take this apology in good faith and see it as remarkable, especially coming so many years before the #MeToo movement. Others interpret it as a perfunctory, carefully worded non-apology, written to evade legal consequences. Regardless of one’s beliefs about his sincerity, it’s clear that “media and fans didn’t do a really good job reckoning with it when he was alive,” sports reporter Lindsay Gibbs said on Slate’s podcast “Hang Up and Listen.” Gibbs wrote critically of Byrant’s legacy when he retired in 2016. “It makes sense that it would be even more tough to discuss when he’s passed away, especially so tragically. I’m seeing two extremes. … And really, neither of those are sufficient.” Gibbs points out that the truth is muddled and Bryant “never really properly grappled with it.” Bryant’s “work in women’s basketball, and his relationship with his daughter,” she writes, “it all exists.” “It’s been interesting seeing the primary identity by which people view Bryant. For some, he will always primarily (only?) be a person accused of sexual assault,” wrote Washington Post reporter Eugene Scott on Twitter. “It’s almost as if he has no identities other than that.” Boston Globe writer Jeneé Osterheldt replied, “The nuance is always missing in this era of extremes.” None of us should be surprised at the lack of nuance in any of this, or the fact that Bryant was never encouraged to evolve. Our legal system isn’t set up for nuance or evolution. It’s an adversarial system that pits the accuser against the accused, forcing them to battle it out inside and outside the courtroom until one of them calls it quits, or a jury decides guilty or not guilty. This is why so many survivors of crime, especially sexual assault, decide that the all-or-nothing options before them are unsatisfactory, and opt out of the system altogether. Recently, the New York Times podcast “The Daily” looked into why, among the over 80 women who came forward with similar and damning accusations against movie mogul Harvey Weinstein, only two are complainants in the current trial against him in Manhattan. One would-be complainant, Lucia Evans, described how various lawyers discouraged her from participating in the criminal case and instead focus on a civil suit. “The narratives I heard the most often were, it’s going to be a long, drawn-out, painful process,” Evans said. “They’re going to tear apart your background, your life. They’re going to talk to everyone you’ve ever worked with, everyone you’ve ever been in a relationship with, find anything they can to discredit you. And it’s hard on you. It’s hard on your family. They’ll go through your trash and find every single thing you’ve ever done in the past, and blow it up out of proportion, and shame you, and just ruin your life, basically.” Her friends and family members told her the same thing. She stuck with it, but prosecutors dropped her charge when they became aware of contradictory statements a friend claimed she had made about the encounter with Weinstein, after which Weinstein’s legal team took the opportunity to portray her in the media as a liar and an opportunist. Proponents of restorative justice see this as reason enough to reconsider the way we handle sexual assault allegations. “This is hard to say, but i am nervous that the idea that Kobe ‘was not held accountable for his sexual assault’ means, ‘Kobe did not go to prison,’” activist and human rights lawyer Derecka Purnell wrote on Twitter. “I don’t think that Kobe should have gone to prison. that does not mean that he was innocent. I believed that he harmed her. I just have no idea, along with everyone else besides Kobe and his rape survivor, whether he was ‘held accountable.’ And rather than assuming that he was not, I hope that we follow the work of radical people doing transformative justice work to understand ‘accountability.’” Bryant was 24 at the time of the rape allegation and died at 41; he may very well have grown and accepted responsibility in that time, or after. He had, after all, shown a willingness to listen to others and change his mind on other hot-button issues, such as the media portrayal of Trayvon Martin after his shooting death. But the legal system, including the secretive terms of the settlement, precluded that kind of growth publicly, and did nothing to encourage it privately. And now he is gone, so we will never know what might have happened under a system that allowed for nuance and encouraged real accountability. |