Oklahoma Woman Imprisoned For Boyfriend’s Abuse Gets Chance at Freedom

Tondalao Hall has served 15 years for allegedly ‘failing to protect’ her kids from their father’s violence. A parole board will now decide if that’s enough.

On October 8, the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board will hold a commutation hearing to decide whether to release Tondalao Hall, a 35-year-old mother of three who has spent 15 years behind bars under the state’s “failure to protect” law, which held her responsible for abuse inflicted on two of her children by their father.

In 2006, Robert Braxton pleaded guilty to abusing his children, including fracturing the ribs and femur of both his toddler son and his 3-month-old daughter. He was released that day, given two years time served plus eight years of probation. Hall, who was 20 at the time of her arrest, entered a “blind plea” of guilty—without a deal for her sentence—on the advice of her public defender. The judge, arguing that she lied by not testifying more forcefully against Braxton, sentenced her to 30 years in prison.

The case has received national attention during Hall’s several attempts at commutation. She first tried in 2015, and made it to the second round of the two-step hearing process, where she was denied. Last year, she was denied before making it to the second round.

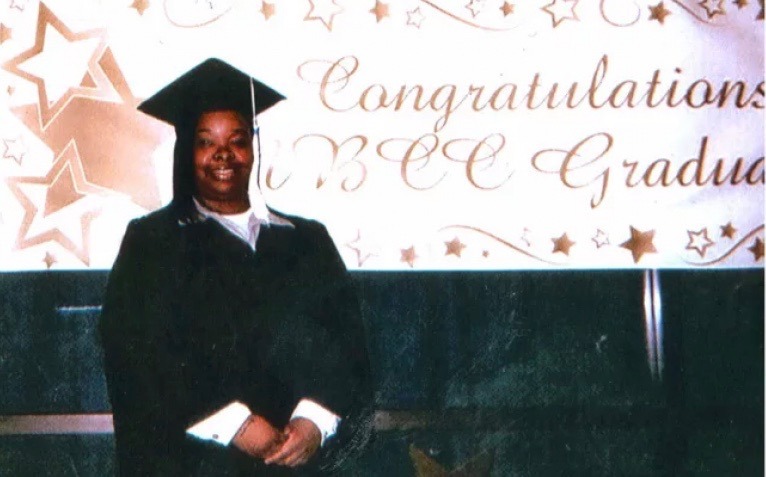

Still, advocates and Hall’s attorney, Megan Lambert of ACLU of Oklahoma, are confident that her chances have improved. For one thing, three of five parole board members are new since Hall’s last attempt, and were appointed by a governor who has expressed a desire to increase the number of parole requests that are granted. The board voted unanimously for Hall to move to the second round, in which she will attend a hearing via video conferencing. She will speak to the board along with her attorney and the instructor who helped her attain her cosmetology license in prison.

Hall’s advocates have another reason for optimism: After a letter-writing campaign by local advocacy organization Project Blackbird resulted in more than 800 letters to Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater, Prater wrote a letter of support to the parole board, explicitly advocating for Hall’s commutation, the first time an Oklahoma district attorney has done so.

“These are the most green lights that she’s gotten,” said Candace Liger, an organizer with Project Blackbird who has been advocating for Hall since her first attempt at commutation.

The DA made clear, though, in his letter, that he doesn’t think the prosecution or the judge erred in Hall’s case. He said that Hall’s testimony as a witness against Braxton was inconsistent with what she had told prosecutors, and quoted a letter Hall wrote to the judge saying “Lying led me to prison.”

Angela Beatty, a YWCA domestic violence advocate who provided expert witness testimony in Hall’s post-conviction application, said that her case highlights a common problem in Oklahoma, which has the highest incarceration rate in the nation and incarcerates women at almost double the national rate. A 2014 study by the University of Oklahoma found that nearly half of the inmates surveyed grew up with a violent father and that more than 66 percent had a partner who physically abused them in the year prior to their incarceration. In a notarized declaration, Hall describes having been physically and psychologically abused by Braxton. “I never knew what mood he would wake up in,” she wrote. “It was like living with Jekyll and Hyde.” Braxton’s attorney could not immediately be reached for comment.

Beatty said the way Hall’s case was handled was inconsistent with best practices for handling victims of domestic violence.

“This is someone who has experienced recurring abuse from this person who has access to her, is threatening her, and then is glaring at her on the stand—now, we talk about things like emotional safety, and work with clients to prepare them to testify, because that is a traumatic experience,” Beatty said. “Understandably she was in fear of her life.”

Indeed, during the trials of Braxton and Hall, they were transported from jail to the courthouse together, and Braxton was permitted to send letters to Hall throughout the two years leading up to their trials. In her declaration, Hall wrote:

We were transported to the courthouse together. He would threaten me and berate me about my decision to testify. He called me a “bitch” and teased me, saying “What can you tell? You think it’s gonna help you?” I would arrive at the courthouse shaking and in tears. I had to make a complaint before we were finally transported separately. Even when we arrived in different vans, we were still placed in holding cells right next to one another at the courthouse. He asked me why I was testifying against him and threatened to “kick my ass” because of it. I felt terrified and sick to my stomach. I could never get away from him.

Lambert said that Hall did not lie on the witness stand—rather, she was prohibited from testifying about Braxton’s abuse of her because the prosecution failed to file a required notice informing the defense of the crimes the prosecution planned to introduce into evidence. Lambert said when she asked Hall about the letter she wrote apologizing to the judge for lying, Hall said she didn’t understand why she had been cut off from testifying and thought it was her fault she was never able to testify to the full extent of Braxton’s abuse. “It shows how little [the prosecution] understood the facts of the case,” Lambert said. “In their minds, Toni and Robert were truly co-defendants, but in fact, Toni was another victim of his abuse.”

If Hall does not receive commutation, she will not be able to apply again for three years. Still, an application for post-conviction relief is pending, Lambert said, which they will pursue if her commutation is denied. But in that hearing, the judge who first sentenced Hall would be the presiding judge.