‘No Beds Left’: Houston’s Jail is a COVID-19 Superspreader

On Tuesday, Harris County Commissioners will decide if the D.A. and Sheriff will get more money to continue their neglect in the face of a public-health crisis.

As of Sunday, there were 8,889 people incarcerated inside Houston’s Harris County Jail, the largest facility of its kind in Texas. Of that number, 7,772—more than 87 percent—are being held pretrial. Nearly half of the people held in the jail, according to the county’s online jail population database, have been arrested on nonviolent charges.

For about a month, beginning last March, there was a sharp, but brief, decline in the jail’s population. Since mid-April, when the population hit its low of around 7,300, the number of people held at the Harris County Jail has steadily swelled. Over that same period of time, COVID-19 infection rates have traced a similar, unrelenting trajectory. More than 2,600 people incarcerated at the jail and around 1,200 workers tested positive for the disease as of Jan. 15. Six incarcerated people and two employees have died.

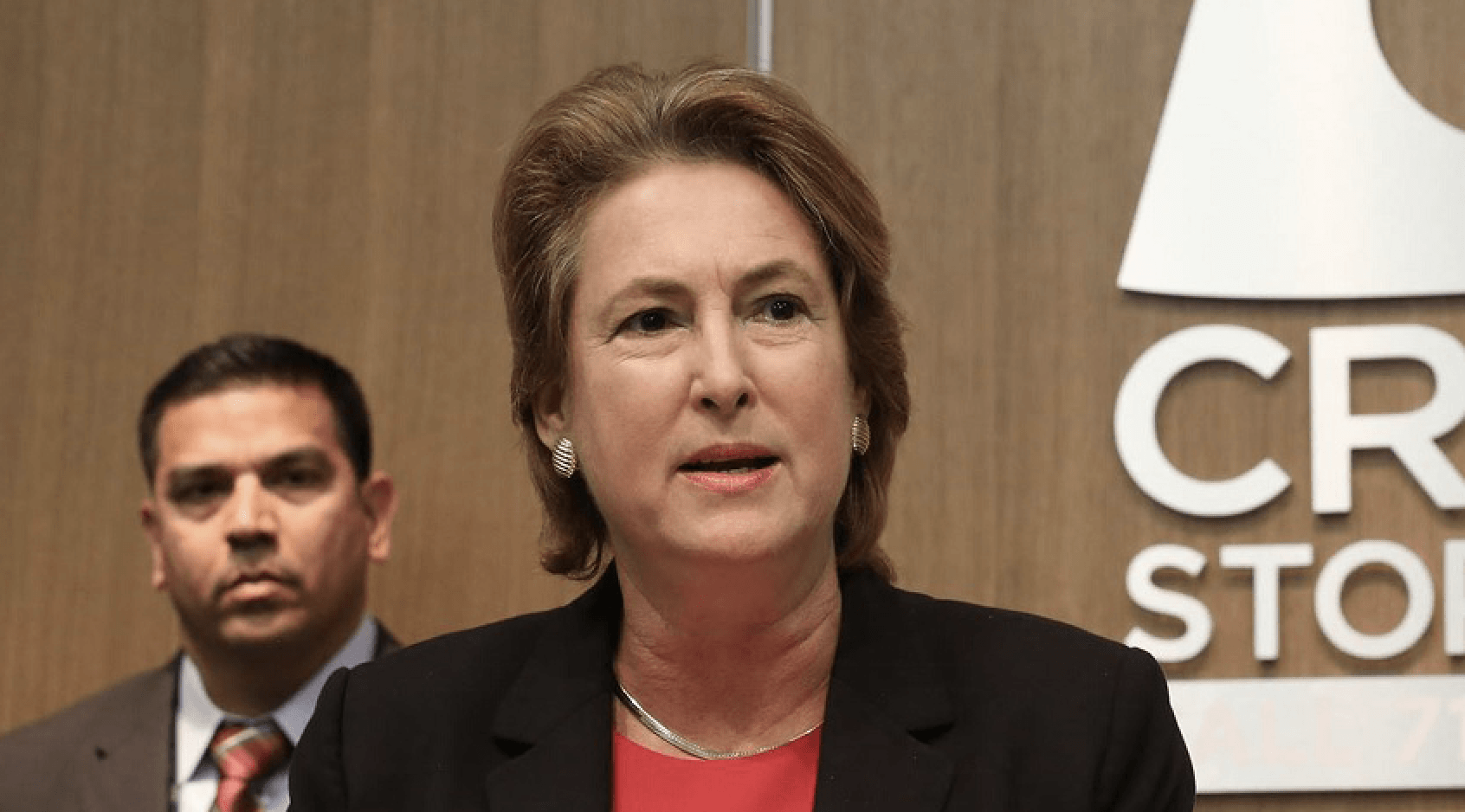

Rather than addressing this crisis, Houston-area politicians and law enforcement leaders have, for weeks, passed blame between one another for the number of people held in close quarters at the jail. According to multiple interviews and emails obtained by The Appeal, justice reform advocates have placed blame on three institutions: the Houston Police Department, which has continued to arrest people at a nonstop clip; local judges, who have failed to expedite the cases of those nearly 7,800 people being detained pretrial; and the office of Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg, which has repeatedly rejected pleas from Harris County Sheriff Ed Gonzalez to release thousands of pretrial detainees during the pandemic.

“Rather than mitigate the public health catastrophe that inevitably results from holding thousands of people in cages in close quarters every night, the police and the District Attorney’s office have continued business as usual, filing enormous amounts of low-level charges that ultimately put individuals and the community (including law enforcement) at risk,” Jay Jenkins, Harris County project attorney for the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, a nonprofit justice-reform group, told The Appeal via email.

Tomorrow, the Harris County Commissioner’s Court—the county’s highest governing body—will meet to debate funding increases for Ogg’s office and the county’s sheriff’s department. The vote will determine whether Houston’s law enforcement apparatus will have more resources to continue its neglect in the face of a public health crisis.

According to emails obtained by The Appeal, both Gonzalez and members of the Harris County Justice Administration Department have recently asked county judges and the DA to either decrease bonds for pretrial detainees or to release those people from jail. Gonzalez supplemented his requests with the names of the thousands of detainees he considers eligible for bond reductions or release, but Ogg’s office has so far taken no action on virtually all of the cases. Her office did not respond to a request for comment from The Appeal.

“As a result of the pandemic and the holidays, the jail has practically no beds left,” Gonzalez stated in a Jan. 11 email to numerous county officials. “With outsourcing not being a viable option, it would be extremely helpful if Judges could prioritize jail cases on their dockets.”

In a separate email sent the same day, a county employee complained of the inaction from Ogg’s office. The employee, who requested anonymity because of their close relationship with Ogg’s office, wrote that the sheriff’s office “recommended 1,619 releases” to Ogg, but “the DAO agreed to 16.”

In a Jan. 21 court advisory—filed as part of the Russell v. Harris County lawsuit regarding bail practices in the county—Ogg’s office stated that, of the 1,543 people recommended by the Harris County sheriff for release, it would agree to reduce bail for just 60. (The Houston Chronicle first reported on the filing on Thursday evening.)

“Of the 1543 defendants on the list sent to the District Attorney by the Harris County Sheriff, 1148 defendants have an external hold or their pending case is violent,” Ogg’s office wrote. “The District Attorney objects to lowering the bail for any of these individuals’ cases.”

In the time between Gonzalez’s email and Ogg’s statement, more than 27,000 people in Harris County tested positive for COVID-19. As of Sunday, nearly 300,000 people have tested positive for COVID-19 countywide. At least 2,855 have died.

In March 2020, the Harris County court system was briefly shut down to prevent the spread of COVID-19. In-person courts reopened in June, albeit on staggered schedules, with limited in-person meetings and using teleconferences whenever possible. (In mid-2020, the county resumed jury selection proceedings by holding them at the 8,000-seat NRG Arena to abide by social distancing rules.) Jury trials resumed on Oct. 1, with a few exceptions.

According to Jay Jenkins of the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, the slower pace has turned “pretrial incarceration into an indefinite sentence.”

But the county’s court system had already been dealing with a backlog of cases before the pandemic, due in part to damage sustained to the court’s buildings in 2017 because of Hurricane Harvey. In June, the Justice Management Institute, a Virginia nonprofit that works closely with the county, issued a report warning that, even under perfect operating conditions, the court system would take years to get through its backlog of cases and that the situation had become “too great to overcome” using traditional methods. The organization urged the county to dismiss or release all people held pretrial on nonviolent felony charges older than nine months, create a specific court of judges to deal solely with the backlog, process new cases using strict timetables, and expand the number of charges eligible for police or prosecutorial diversion.

“This situation isn’t effective justice, this isn’t a fair way to treat victims, and this isn’t fair to the individuals whose lives are on hold or who are sitting in jail waiting for the court system to adjudicate their case,” Elaine Borakove, president of the Justice Management Institute, wrote to the Commissioner’s Court on June 1. “Given the gravity of the circumstances, every entity in the criminal justice system must make uncomfortable, but necessary changes.”

But the county and its judicial system have largely opposed such measures.

Houston’s jail overcrowding during the pandemic exposes a moral test that faces virtually every jail system in America. Some lawmakers, prosecutors, and other law enforcement officials have authorized the release of nonviolent detainees during the pandemic. But, so far, nearly all have not released allegedly “violent” offenders who are also held in jail pretrial and who are also at risk for contracting and spreading the coronavirus.

“The power exists among the various stakeholders—sheriff, judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys and county officials—to safely and significantly reduce the jail population,” said Amanda Woog, executive director of the Texas Fair Defense Project. “They need to work collaboratively to plan for thousands of dismissals and releases so no person is caged in these unsafe conditions during a deadly pandemic.”