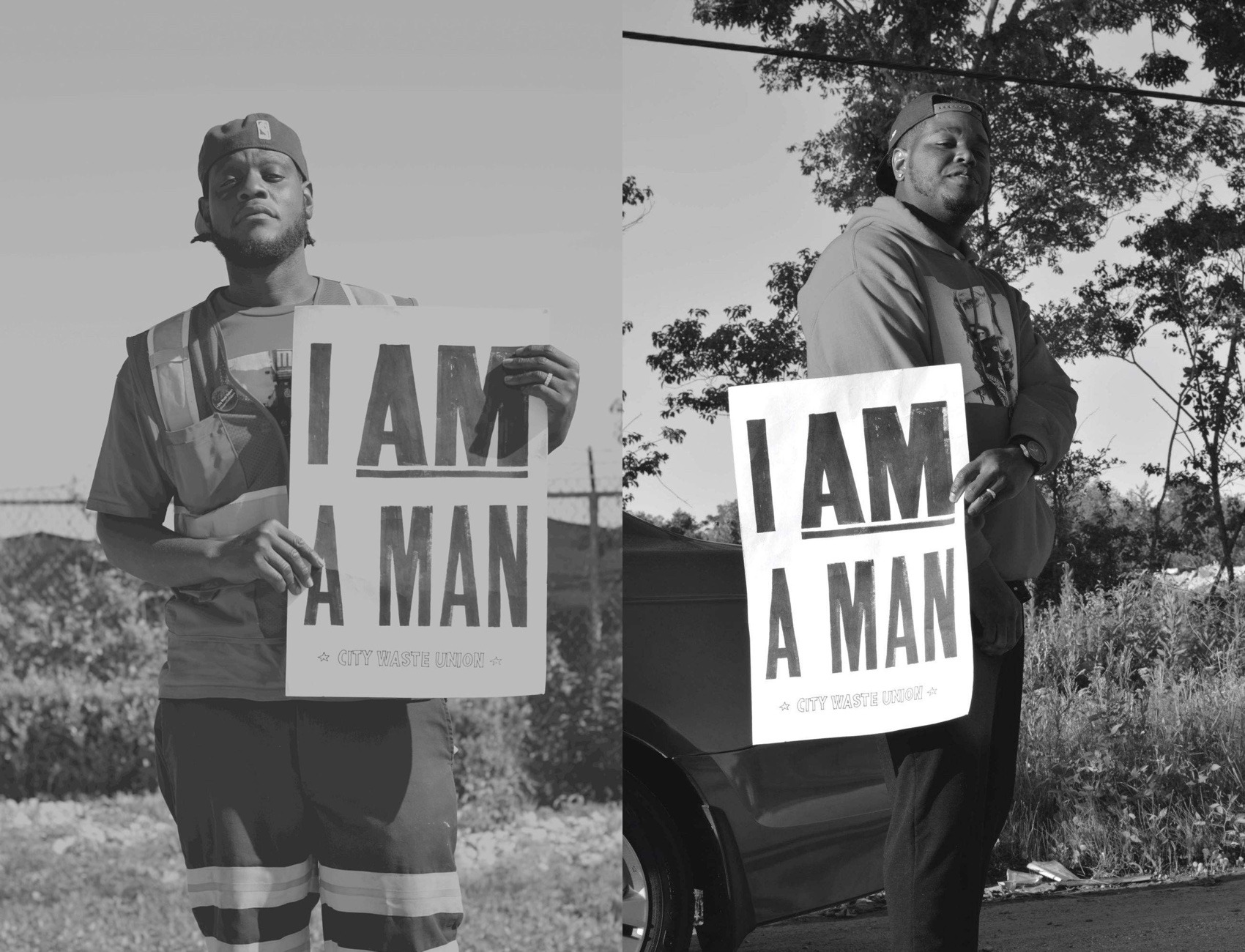

Some Of The Hardest-Working Frontline Employees In New Orleans Are Living Paycheck to Paycheck

Garbage collectors in the city are striking for $15 an hour, hazard pay, and PPE.

On May 5, trash collectors in New Orleans went on strike, demanding $15 an hour, $150 a week in hazard pay, proper personal protective equipment, and that broken trucks be fixed.

“A garbage truck worker is a frontline worker,” said Jerry Simon, who works as a hopper—riding on the back of the truck and hopping off to collect garbage. “We feel like we need some kind of compensation for us dealing with this.”

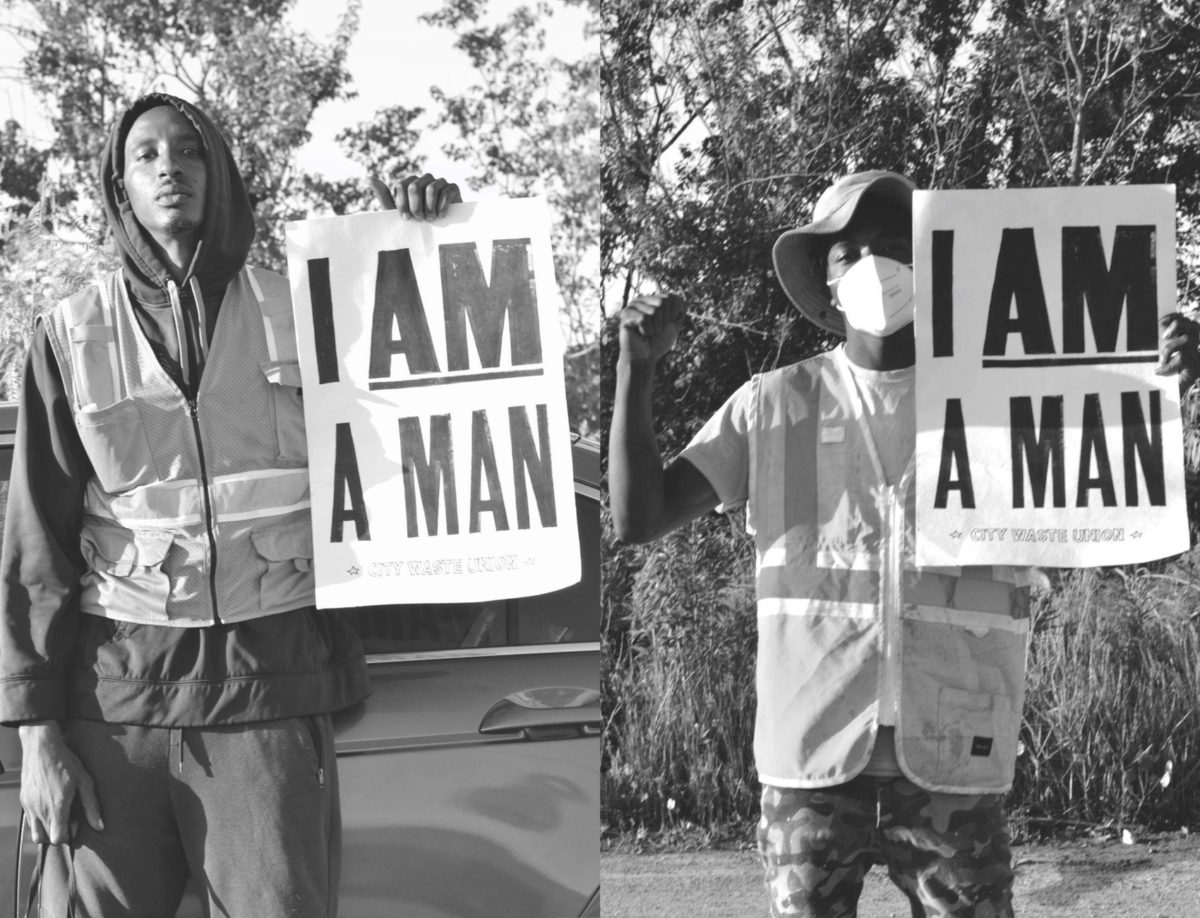

Sanitation workers need proper protective equipment, such as puncture-resistant gloves, and face and eye protections, said Wendy Heiger-Bernays, a professor of environmental health at the Boston University School of Public Health. COVID-19 is transmitted through respiratory droplets expelled when an infected person sneezes or coughs—or even, scientists fear, when they exhale or talk.

“If that waste were in a hospital it would be treated very differently, right? It would be treated as biological waste,” she said. “They’re hauling the trash that’s coming from our homes and businesses where we are disposing of diapers that may contain virus, tissues that may contain virus, and other potentially contaminated material.”

When Simon would get home from work, he worried about transmitting the novel coronavirus to his children.

“You got to go inside and tell your child Daddy can’t hug you right now,” he said. “I can’t kiss you because I don’t know, my clothes could be contaminated.”

Hoppers can work 15 hours a day without any paid breaks, according to City Waste Union spokesperson Daytriàn Wilken, whose uncle is a striking hopper. Between 3 and 4 most mornings, at least 50 hoppers arrive at the yard to be assigned a truck. They can wait outside for up to an hour and a half; they have to share just one portable toilet, she said.

“Whatever they say, goes,” said Simon. “That’s why we here today. We’re tired of it.” Simon works for PeopleReady, a private staffing company. PeopleReady is a subcontractor of Metro Service Group, which contracts with the city.

Metro spokesperson Virginia Miller told The Appeal in an email: “These hoppers are on Metro property for a short period of time per day and we are looking at measures to be taken to make the work environment better for that short period of time.”

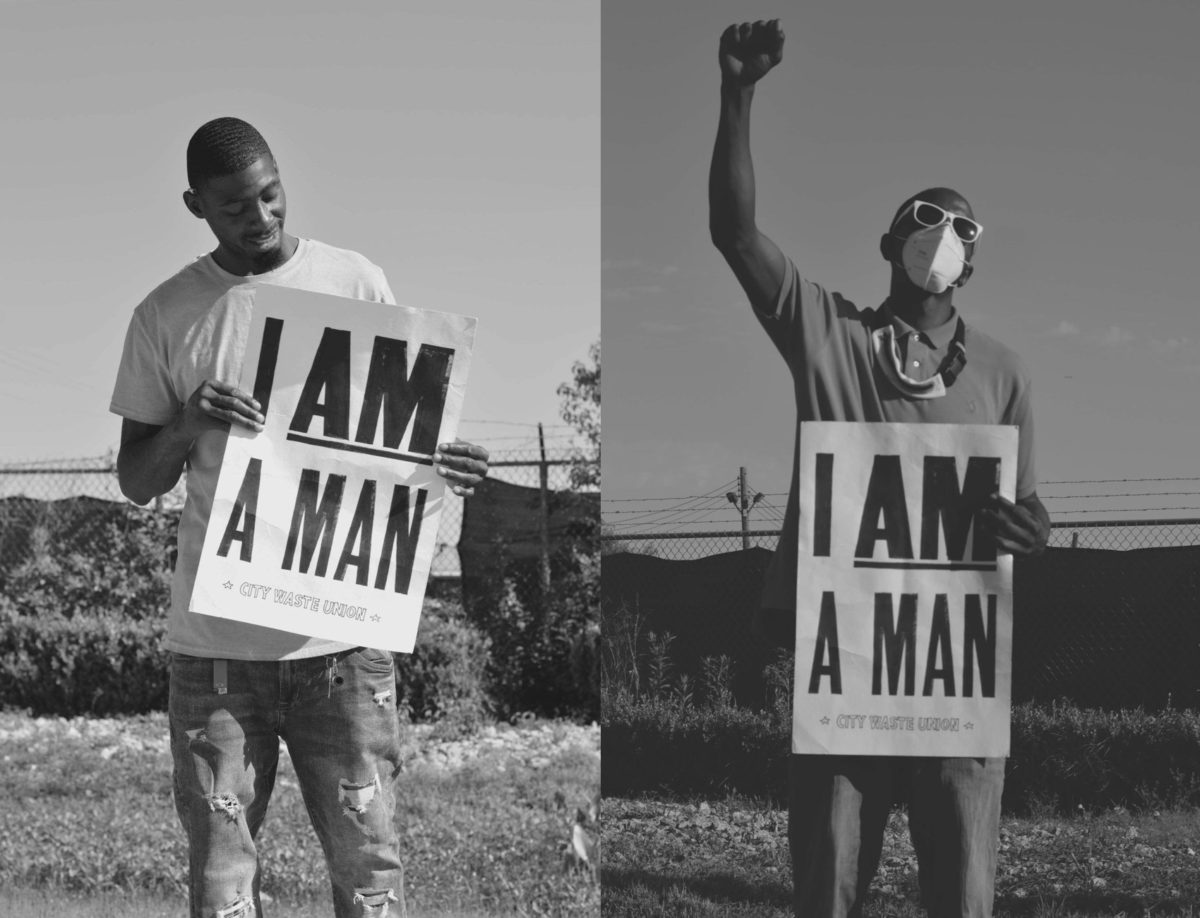

Fourteen hoppers remain on strike, said Wilken. An online strike fund has been created to help the workers get by. They also rely on each other, said Simon.

“Been trying to help each other out. Trying to stick by each other. Try to have each other’s backs,” he said. “When you see the fellows, we keep each other upbeat. Talk about it because it’s therapeutic.”

The union says the hoppers are paid less than the city’s living wage ordinance, and are not provided paid time off. The New Orleans living wage ordinance, which went into effect in 2016, requires that city contractors and subcontractors pay their workers $11.19 an hour and provide at least seven days of paid leave.

According to the union, hoppers earn $10.25 an hour if they work four days or less in a week, and $11 an hour if they work five days or more. Wilken’s uncle’s paystubs from this year show he earned an hourly wage of $10.25. If he worked overtime, he earned up to $16.50 an hour.

“We shouldn’t be one of the hardest workers in the city and have to live paycheck to paycheck,” said Simon. “We just want what we deserve.”

In a statement to The Appeal, Miller said Metro Service Group has confirmed that all workers are receiving the living wage. “Should any hopper be found not to have received that amount, Metro will work with PeopleReady to ensure remedy,” she wrote in an email to The Appeal.

City spokesperson Beau Tidwell said in an email that “Metro is required to fully comply with the City’s living wage requirement. The City is currently evaluating complaints as to Metro and will respond as may be appropriate.”

Some workers who were brought in to temporarily replace those on strike may have been paid even less than the hoppers and faced the same risks. Incarcerated people from the Livingston Parish’s Transitional Work Program worked as hoppers for four days, according to Miller. In Louisiana, the company that places prisoners in jobs—in this case, Lock5 LLC, according to NOLA.com—can take up to 64 percent of their earnings per paycheck.

Both Metro and the city defended the use of incarcerated workers. “We at Metro believe that trustees who are close to their release date, and who are willing to work deserve an opportunity to earn some money and that affording them this opportunity is good for society as well,” Miller wrote to The Appeal. Tidwell said in an email that the workers “gain valuable work experience necessary for return to a productive life.”

Alfred Marshall, an organizer with New Orleans Workers’ Center for Racial Justice, called the practice “modern-day slavery.”

“It hasn’t went away,” said Marshall, who was previously incarcerated. “It just transformed.”

New Orleans Workers’ Center for Racial Justice, which supports the strikers, “was founded as a workers’ rights and racial justice response to the man made disaster called hurricane Katrina,” according to the group’s website. Thousands of low-income, predominantly Black, New Orleanians could not afford to evacuate. Once the storm hit and the levees broke, they were stranded on the roofs of their homes, inside a flooded jail, and at a sports stadium turned shelter for days.

“This country has stole from us a long time. And it’s stealing from the people at the bottom. They don’t treat us right,” Marshall said. “They use Katrina to send water on us,” he continued. “We was left to drown and let the world know—we still drowning.”

In addition to a higher hourly wage, the hoppers are also demanding hazard pay and proper protective equipment. Metro Service Group supports hazard pay for all sanitation workers, but can only provide it if it is included in the HEROES Act, a federal stimulus package that Congress is considering, Miller said.

“This is an issue that we have been on the forefront of proactively trying to solve, as the low bid nature of our contract juxtaposed against the number of households we serve three times a week makes an increase infeasible without inclusion in the Heroes Act,” she wrote.

According to Miller, Metro has purchased proper protective equipment for workers, including 15,000 masks, 2,000 pairs of gloves, additional bandanas, and hand sanitizer. Hoppers were provided with gloves, masks, and eye protection, according to PeopleReady spokesperson David Irwin. The striking workers are welcome to return, he wrote in an email to The Appeal.

But the union says workers have only been provided one pair of nylon gloves and one mask per week. “If it is available, where is it and where has it been?” said Wilken.

Simon is eager to go back to work, he says, but changes must be made.

“Just trying to stand up for what we believe in,” he said. “This is for all the garbagemen all around the world who feel the way we feel.”