My Friend Should Have Been Released from Prison. Instead, He Died There of COVID-19.

James ‘Bumpy’ Bennett, who had twice survived cancer, was 71 and had served 48 years of his life without parole sentence.

This piece is a commentary, part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

On May 18, while organizing a virtual town hall about the effect of COVID-19 on vulnerable populations within the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, I received dreadful news: A man I had known for over 20 years had passed away from COVID-19 at State Correctional Institution, Huntingdon.

“My man Bump died yesterday,” read a text message from a friend. I closed my eyes, leaned back on the couch I had been using as a makeshift work station for the past several weeks, and looked up at the ceiling in despair and anger. Bumpy, I said to myself, WTF?

James “Bumpy” Bennett had languished in prison for 48 years. At the time of his death, he was 71 years old. He had beaten cancer two times over and had recently had his hip replaced, a procedure that his family and friends fought the DOC hard for. Because of his age and health, and his good behavior, I believe he should have been released long ago.

In 1972, Bumpy was sentenced to life without parole for first-degree murder and began his journey through the DOC. He earned the moniker “Bumpy Johnson” after the legendary Harlem gangster who was admired and respected because of his charisma and demeanor. Like many older lifers, Bumpy was a stabilizing presence in the lives of younger prisoners like myself who were still hotheaded and full of rage.

Our paths crossed in 2000, when we were both incarcerated at SCI Huntingdon in central Pennsylvania. I had been sentenced in 1991 to life without parole for being an accomplice to first-degree murder as a lookout for a drug-related homicide. The offense happened on my 16th birthday.

In 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that people incarcerated on unconstitutional mandatory life without parole sentences for crimes they committed as children could petition for new sentences. In 2018, after 27 years behind bars, I was released, and since then I have been a staunch advocate for decarceration.

Like everyone else on the planet, my work has been drastically altered in the last several months by the COVID-19 pandemic. The disease has attacked the U.S. prison system, with 47,275 positive cases and 542 deaths, and the urgency is magnified by the fact that unlike in society, social distancing is impossible in a prison setting. The only way to mitigate against COVID-19 in prison is through decarceration, focusing on releasing the most vulnerable populations, who the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention define as persons over the age of 65 and people with compromised immune systems.

But Pennsylvania was slow to pursue avenues of release for vulnerable people in its prisons. Many leaders are strongly opposed to criminal justice reform, and leading this opposition are the state victim advocate Jennifer Storm and the state District Attorneys Association. Both played a role in hamstringing legislators, who were ultimately unable to agree on a bill that would have granted early release to certain people convicted of nonviolent offenses.

With the legislation dead, advocates pressured Governor Tom Wolf to exercise his power to temporarily suspend a prisoner’s sentence in light of the pandemic. But his reprieve order was narrowly drawn; it excluded violent offenders and despite its objective of releasing 1,200 to 1,800 prisoners, in a little over a month, it has managed to release only 147.

Reprieve is dead. The mass incarceration lobby is celebrating while prisoners like Bumpy are dying.

Bumpy was among the more than 700 lifers over the age of 65, and more than 400 who have served over 40 years. They account for 10 percent of the entire DOC population. Statistically, this age group has the lowest recidivism rate—4 percent—compared to the state’s general recidivism rate for all offenders, which hovers between 43 to 46 percent within three years of release. Furthermore, people with serious offenses who have served over 25 years and are over the age of 50 have rates of recidivism substantially lower than nonviolent offenders. If release was based on public safety and not politics, these groups would be first in line. Unfortunately, they are not.

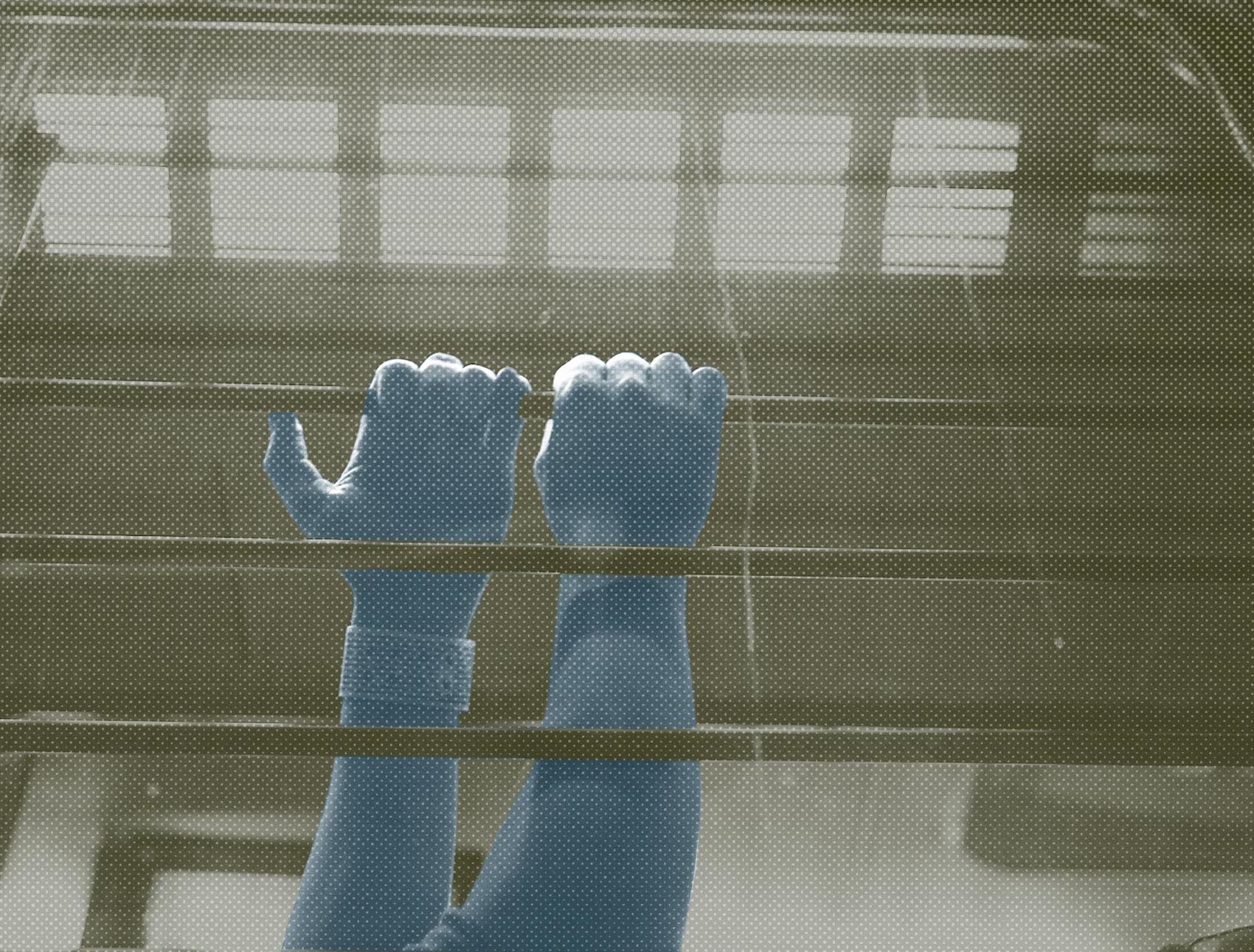

Meanwhile in prisons like SCI Huntingdon, seniors are living in fear of imminent death. Huntingdon has had the most COVID-19 cases in the DOC—over 171. In May, in less than two weeks, Huntingdon went from 17 cases to over 100. Huntingdon houses hundreds of prisoners on tiered ranges with narrow walkways. Hundreds of men at a time from each range must use a large communal shower. At the front of each cell are steel grate bars so that if a prisoner coughs or sneezes, it mists out onto the tier. In the mid-1990s, central air was installed on the blocks; however by the early 2000s, the system was already in disrepair. The fact that Huntingdon had to turn its gym into a quarantine area demonstrates that it has no effective isolation units.

Although more thorough testing would not solve the problem, it would allow for more precise quarantine measures and illuminate a pattern of hotspots the prison can track. It is the least the prison can do to prevent more deaths of its vulnerable populations—and testing on this scale is not new. In 1992, as a result of a lawsuit, the DOC tested its entire population for tuberculosis and developed a comprehensive TB clinical program to settle the lawsuit. In accepting the settlement the court noted that, “The 1992 TB policy has been highly successful in preventing what might otherwise have been an outbreak of active tuberculosis.”

Last month the Abolitionist Law Center, Amistad Law Project, and ACLU Pennsylvania submitted a letter to the DOC, requesting it initiate universal testing. Secretary of Corrections John Wetzel has opposed testing the entire state prison population. However, absent release, mass testing is the only other option the DOC can take to prevent future COVID-19 outbreaks within its prison system.

I was fortunate to have my freedom in 2018, but Bumpy was denied his chance for release or reprieve because of Storm and the state District Attorneys Association. Storm and her cohorts appear not to care that aging, incarcerated people are at risk of being sacrificed during the COVID-19 pandemic. They have pushed an ugly and racist vision of endless retribution. Governor Wolf also bears responsibility because he should have exercised more leadership in this moment. It is past time that there is a concerted effort across all social justice movements to repudiate mass incarceration’s ethic of vengeance, demand decarceration, and out-organize the forces standing in the way. One more death is one too many.

Robert Saleem Holbrook is the director of organizing for the Abolitionist Law Center based in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.