Political Report

Massachusetts Lawmakers Consider Restoring Voting Rights, but Organizers Are Not Waiting

Advocates pursue many fronts to push for incarcerated individuals to have electoral voice, two decades Massachusetts restricted the franchise.

This article is part of a state-based series on disenfranchisement.

Massachusetts moved away from universal suffrage in 2000, stripping incarcerated individuals of their right to vote through a constitutional amendment. Nearly two decades later, organizers inside and outside state prisons are working for now-disenfranchised Bay Staters to have a say in the electoral process.

The Emancipation Initiative, a group that advocates restoring suffrage to all people in prison, has been running a project called #DonateYourVote since 2016. The idea is to pair an incarcerated person and a free person who commits to voting according to his or her disenfranchised partner’s preferences. More than 140 such pairs formed in the 2018 elections, according to project organizers.

In January, Senator Adam Hinds introduced a proposed constitutional amendment that would restore incarcerated individuals’ voting rights. “It’s scary to me that the ability to have a voice in a democracy and the laws that impact the democracy can be removed,” he told me.

If this measure passes, Massachusetts would repeal the practice of barring people from voting because of a felony conviction. That reform has a long road ahead, though. The proposed amendment (S.12) would need to be adopted by lawmakers in two separate legislative sessions and then by voters, which could not occur before 2022 at the earliest, and a regular bill (SD26) must also pass.

Neighboring Maine and Vermont already have no such disenfranchisement, and Massachusetts was like those states until Republican Governor Paul Cellucci and other state politicians pushed for restrictions in an era known for its tough-on-crime politics and harsh sentencing schemes. In 1997, a group incarcerated at the Norfolk state prison attempted to create a political action committee that would spread information about elected officials’ positions on criminal justice issues, encourage people to vote while in prison, and change the state’s carceral policies. “Our whole point now is to make prisoners understand that we can make changes by using the vote,” Joe Labriola, a member of that group, said at the time. “We have the ability to move prisons in a new direction.” In response, Cellucci proposed stripping incarcerated people of their political rights. He issued an executive order banning certain organizing activities within prisons and he targeted their vote, too. “It’s outrageous that these prisoners have these voting rights,” he said. “We should be thinking about the victims.”

The Democratic-run legislature then twice passed a constitutional amendment to bar people convicted of a felony from voting while incarcerated. The amendment was placed on the ballot in November 2000. State voters approved it by a large majority.

Senator Pat Jehlen, who opposed this measure at the time, recalled a desire to block political activism when I asked her what had spurred its adoption. “It really was that there were people in some of the prisons that were organizing,” she told me. “There was that, and there was the argument which I don’t believe was true that they would overwhelm the local community” by all registering in the place they were incarcerated, she added. Legislative debates also bear the trace of some politicians’ hostility toward anything short of strict custodial control. “We decide when they get up and when they go to bed,” Representative Francis Marini said of incarcerated people during the 2000 convention according to transcripts posted online by the Emancipation Initiative. “We won’t let these people run their own life. They should not be allowed to run ours.”

Jehlen added that she had heard little about this issue since 2000, but that much is changing—in Massachusetts and elsewhere in the country.

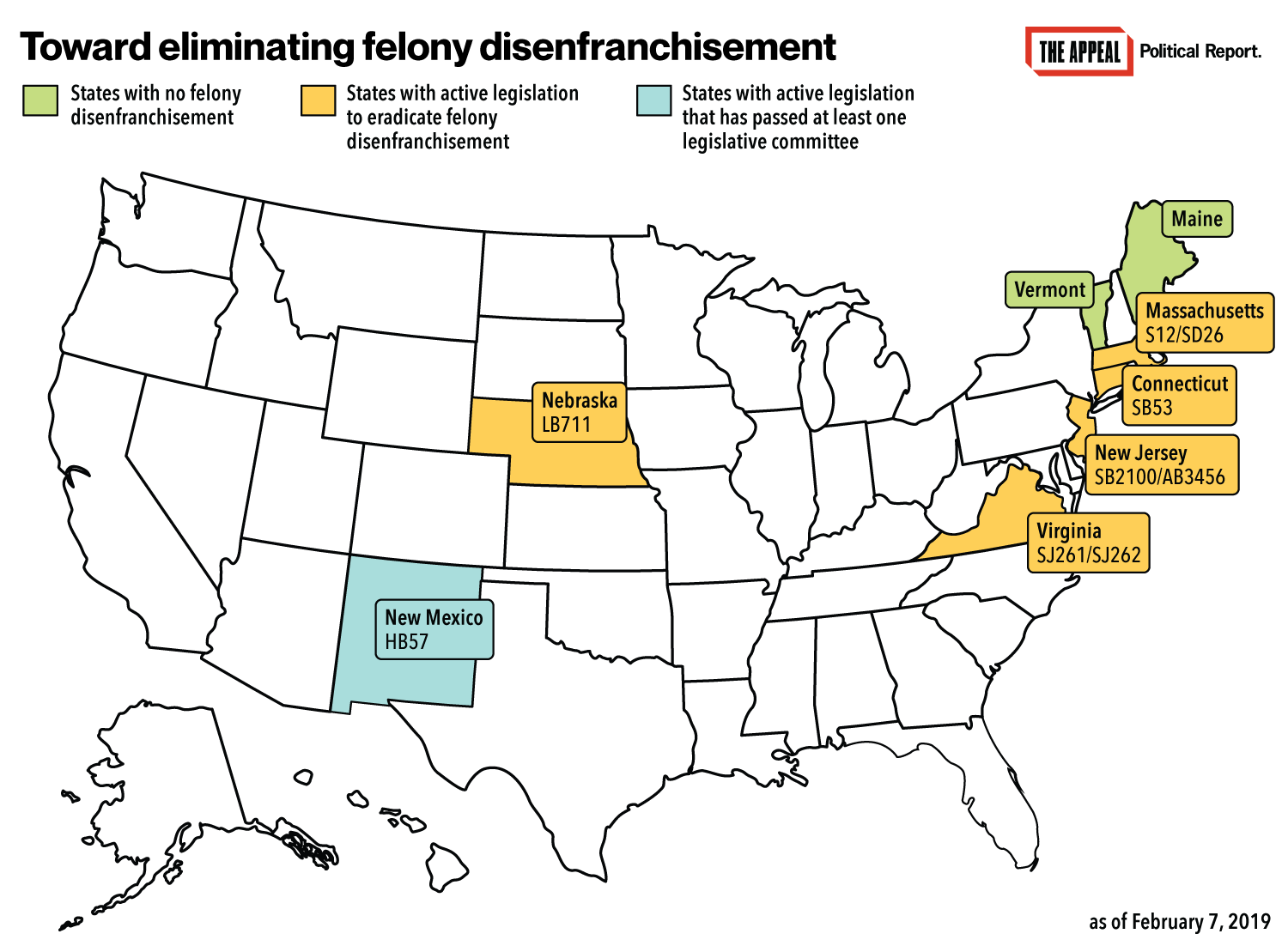

Bills that altogether abolish felony disenfranchisement have been introduced in at least six states in current legislative sessions, and a legislative committee advanced one such bill in New Mexico in January. Last week, 20 national civil rights organizations sent a letter to New Mexico’s legislature in support of ending felony disenfranchisement.

“To have this network of folks who are also working hard on this issue is really exciting,” said Rachel Corey, an organizer with the Emancipation Initiative. “To see this energy come up in different parts of the country is like, ‘OK, we’re not on this island alone.’” She added, “Let’s move to the next level and restore the right to vote to anyone who is impacted by the criminal justice system.”

The Emancipation Initiative has been organizing Bay Staters inside and outside prisons around this goal. Derrick Washington, who is serving a life sentence without parole, founded the Emancipation Initiative in 2012 while incarcerated. He said he has focused on suffrage ever since noticing that the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, makes an exception for punishment of a crime. “It opened my eyes to the reality of my situation,” he said on the phone. “I was a 21st-century slave to a system that is not catering to me or to anyone from the neighborhood that I came from.”

“I can’t impact the people who have designed the environments I’m detained in or are designing the policies that impact me,” he added. “In order to change the fabric of my situation, I would need to have a voice and reshape my environment with the vote. … You have a whole pariah class that are excluded from the process, yet those people are most affected by the laws that are put in place by legislators.”

Today this exclusion disproportionately impacts communities of color. According to a report released by the Sentencing Project, 26 percent of the people that Massachusetts disenfranchised as of 2016 were Black, even though only 7 percent of the state’s voting-age population was Black. A separate Sentencing Project report found that Massachusetts had the country’s largest inequality between the incarceration rates of Hispanics and whites—measures that are tied with each group’s disenfranchisement rate. Outcomes experienced in the criminal justice system inform these disparities. One study of Massachusetts conducted by the Council of State Governments in 2016 found that, among individuals who were convicted, a higher share of Black and Hispanic defendants than white ones received a sentence that included incarceration—as opposed to other forms of punishment that do not induce disenfranchisement. The study did not isolate type of offenses for which people were convicted.

“When you walk through what we’re seeing in the disproportionate arrests of African Americans and how this is targeting people of color in prison, it feels that the original racialized motivation is still what is keeping this in place,” said Hinds, the sponsor of the proposed amendment. Hinds traced the country’s present disenfranchisement statutes to their spread in the decades after African American men secured the right to vote. He called on the state to be “meticulous and deliberate in dismantling forms of discrimination” and to reject “laws that had nefarious intent.”

Hinds acknowledged that the the process of passing a constitutional amendment is arduous, but he added that he believes the politics surrounding this issue have changed since 2000 and that people are now more attentive to concerns of racial justice.

There are 29 state legislators serving today who were present at the 2000 constitutional convention. Seven of them (all Democrats) voted against the disenfranchisement amendment at the time, while 22 (four Republicans, 18 Democrats) voted for it.

At least one of the lawmakers who backed the 2000 constitutional amendment has since changed her views.

Senator Harriette Chandler, who voted for disenfranchisement in 2000, told me that she supports the voting rights of incarcerated people. “I believe it is the right of all citizens to participate in our democracy,” she said in a statement emailed by a spokesperson. “People who are incarcerated are affected by the laws we make just as much as anyone else, and if I have learned anything over the past two decades, it is that we must empower people to have a voice and to use that voice to advocate for themselves and their community.”

None of the other 21 legislators who voted in favor of disenfranchisement in 2000 responded to a request for comment about their current position. One of them is Robert DeLeo, a Democrat who is the state’s current speaker.

By contrast, three of the sitting legislators who opposed disenfranchisement in 2000 (Jehlen, Representative Kay Khan, and Representative David Linsky) told me that they would support this latest effort to undo the practice. “I … over the years have learned that incarceration has been a tool in perpetuating racial inequality throughout the country,” Khan emailed via a spokesperson. She added that “we should help all individuals become more successful members of society, not subject them to further isolation and social exclusion. People in prison are still human beings who have opinions and want to be heard.” Jehlen argued further that avoiding such isolation matters to re-entry given that most incarcerated individuals leave prison. “Maintaining community ties is one of the ways that people avoid recidivism,” she said.

Emancipation Initiative organizers are not waiting for a new constitutional amendment to be adopted to work for people in prison to be heard.

After launching the #DonateYourVote project in 2016, they worked with members of Boston DSA, a chapter of Democratic Socialists of America, in 2018 to draw more people into the project and also to prepare voter guides with information about each race on the ballot. Once paired, the incarcerated and free people were asked to correspond directly.

Nastasia Lawton-Sticklor, a participant who learned about the project through an email from Boston DSA, said it was “out of my comfort zone because I vote in every election and it’s very important for me, and giving that vote up was a really great lesson for me to be in solidarity with people who don’t have that right now.” Corinna Anderson, a member of Boston DSA, framed her interest somewhat differently, noting that she often finds the act of voting incomplete and seeks out “other ways to be political.” “Voting can often feel individualized as a process even though you discuss it with friends and family,” she said. But her experience in 2018 “felt more collaborative,” she said, because it involved “having discussions with someone else about what it means to vote, and about the candidates and the issues, and it’s also a direct service that you’re trying to provide for someone else to have a choice they wouldn’t otherwise have.”

Anderson recounted that she herself had not paid particular attention to the office of state auditor, but that the person with whom she was paired cared deeply about that position. “For him, it was the person keeping the Department of Corrections in check, the one with oversight over the system, so it was important,” Anderson recalled. “It’s important for the people who are incarcerated to have a voice because they are the people who are impacted.”

Corey, the Emancipation Initiative organizer, noted further that incarcerated people also remain impacted by events beyond the criminal justice system. “We’ve separated them from society, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have loved ones who are in the community,” she said. “Their loved ones work and go to school in the community, they have a stake in what is happening in society, in their kids who are in the education system, in healthcare for their families. Folks in prison, against the correctional system’s desires, are still very connected to their communities.”

Corey told me that the group aims to generate enough interest to pair all people who are disenfranchised with someone who retains the right to vote in 2020. Washington said that given the disenfranchisement of people in prison, the Emancipation Initiative hopes to “get people involved, to get organizations involved, to get families involved, getting them to disseminate the information and hold the elected officials accountable to the whole liberal tag that they’re putting on themselves and the government of this state.”

As of Feb. 7, the proposed constitutional amendment was referred to the legislature’s Joint Committee on Election Laws.