Man Sentenced As ‘Career Criminal’ Gets His First Chance At Freedom In 48 Years

Despite a 2015 Supreme Court ruling limiting the mandatory minimum law, few people are seeing relief.

Kenneth Agtuca had been a lifer for most of his life.

Imprisoned for all but six months since he was 17, Agtuca was sentenced to life for unlawful gun possession in 1993 under an unforgiving Reagan-era law, the Armed Career Criminal Act. About 5,500 federal prisoners are serving time on sentences enhanced by ACCA, which carries a mandatory 15-year term and opens the door to life without parole.

In August, Agtuca became one of a handful of prisoners whose sentences were ruled unconstitutional after a 2015 U.S. Supreme Court decision. Having served nearly twice the usual sentence for his crime, Agtuca at 65 is now on track to head home.

“I have traveled full circle and arrived back at the point where I do not believe myself to be a criminal,” the Seattle man said in a letter to U.S. District Judge Robert Lasnik of the Western District of Washington, who resentenced him in August to a time-served term.

A run of Supreme Court decisions capped by the 2015 ruling brought relief to some prisoners who were sentenced under ACCA. The ruling found part of the act to be unconstitutionally vague—it wasn’t clear what qualified a defendant as a “career criminal.” The decision made hundreds of prisoners serving ACCA-enhanced sentences eligible for resentencing.

The Supreme Court limited the prior convictions that qualified a person for sentencing under the act. It did not eliminate prosecutors’ ability to seek ACCA-enhanced sentences, and U.S. attorney’s offices in a handful of jurisdictions continue to regularly use the enhancement against defendants with prior convictions for drug dealing and qualifying violent crimes.

Agtuca was the youngest prisoner at Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla when he arrived there in 1970 under a parole-eligible life sentence for armed robbery. He was awakened just after midnight and walked out of prison in March 1992.

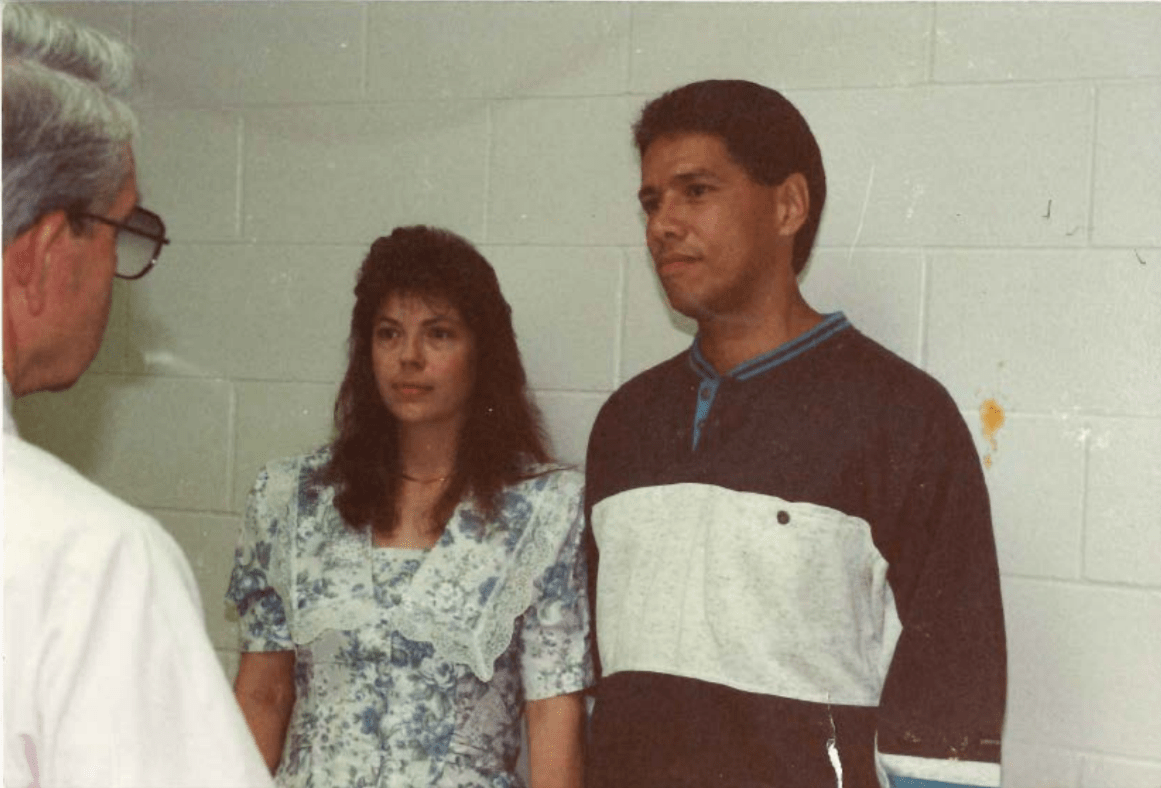

“Looking back,” his wife Susan recalled in a letter to the court, “Kenney was not prepared for freedom and I was very naïve.”

Agtuca was back behind bars by October after robbing a Seattle bank. Then 40, he was prosecuted federally and sentenced to life. Anyone with a gun and three prior convictions for violent crimes or drug distribution offenses could face a 15-year mandatory term, among the longest mandatory minimum sentences in the federal system.

After 25 years in prison, Agtuca crochets pillows for corrections officers, knits winter clothes for prisoners’ children, and raises service dogs.

Agtuca’s Native heritage became a bridge to the outside. He connected with his father’s family and enrolled in their tribe, the northern Wintu. He became an elder to imprisoned Natives, participating in sweat lodge ceremonies and in White Bison, a 12-step program aligned with Native culture. His family has joined him for prison powwows.

“It is important for the younger offenders to see someone who’s been around the block ‘walk the walk,’” said Winona Stevens, executive director of Native American Reentry Services.

It’s not clear how many other prisoners serving ACCA sentences will get the reconsideration Agtuca received. On Aug. 13, Pennsylvania resident Ronald Peppers’s 15-year sentence was revoked after the Third Circuit Court of Appeals found that, like Agtuca, his prior convictions should not have qualified him for an ACCA sentence. A Washington state man previously sentenced to the 15-year minimum under ACCA saw his sentence halved on Wednesday after a similar finding by the Ninth Circuit.

Three years after the Supreme Court decision, prosecutors continue to use ACCA mandatory sentences in patterns that vary significantly from state to state. Whether a defendant faces an ACCA sentence depends on who is prosecuting. Prosecutors in California won just one ACCA sentence in 2016, while New York had only two prosecutions. Florida had 61; Missouri had 29 and Tennessee had 26. Washington state had one ACCA prosecution in 2016.

“It is incredibly arbitrary,” said Molly Gill, vice president for policy at FAMM, an advocacy organization opposed to mandatory sentences.

“One of the ideas behind mandatory minimums … is that they increase the certainty of punishment,” Gill told The Appeal. “When you look at how the law’s applied, that’s really not true.”

Black defendants are far more likely to receive ACCA-enhanced sentences. According to U.S. Sentencing Commission statistics, 70 percent of defendants sentenced under the act in 2016 were Black. Whites, who outnumbered Black defendants that year, accounted for 24 percent of ACCA-enhanced sentences.

Severe sentences and mandatory minimums have long been faulted as unnecessary; the U.S. Sentencing Commission found them onerous and inconsistently applied. They also deliver a compelling advantage to prosecutors during negotiations.

Questioning the government during oral arguments in Johnson v. United States, the case that resulted in the 2015 ruling, Chief Justice John Roberts commented that defendants facing a 15-year minimum will take a deal.

“You said … because there are so many years involved, people will litigate hard,” Roberts remarked to Deputy Solicitor General Michael Dreeben during the April 2015 hearing. “I think because there are so many years involved, people won’t litigate at all. … It gives so much more power to the prosecutor in the plea negotiations.”

About 97 percent of defendants convicted in federal court plead guilty prior to trial. Though ACCA sentences have been declining in recent years, 304 people were sentenced under the act in 2016.

Speaking with The Appeal, JaneAnne Murray, co-chairperson of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers’ sentencing committee, said Johnson and other recent Supreme Court decisions have focused on sentencing enhancements tied to defendants’ criminal histories. Murray said those decisions may indicate the Supreme Court is troubled by mass incarceration.

Murray, a professor of practice with University of Minnesota Law School, said U.S. attorneys’ offices have wide discretion in pulling defendants into the federal system from state courts. She described unlawful gun possession charges as the “low-hanging fruit.” Generally, prosecutors need to prove just two facts to convict: that a defendant has a felony record and that the person had access to a gun.

“State and federal prosecutors may cooperate to charge someone federally because of a particularly egregious criminal record. … Or, more cynically, the local federal prosecutor’s office may simply want to increase case numbers,” Murray said.

Lengthy sentences for people with prior convictions drive incarceration in America. The average sentence for a federal prisoner doubled between 1988 and 2012, and tripled for prisoners serving time on weapons offenses, as prison admissions also increased.

Gill argued that Congress should reduce the length of ACCA-enhanced sentences, make it so older convictions don’t qualify a defendant for harsh punishments, or remove the mandatory minimum entirely.

Currently on his way out of state prison, Agtuca will have a gradual release. He will be moved to a halfway house and slowly returned to free society. He hopes to work as a paralegal and finally make a home with Susan, whom he married in prison.

“I cannot make up for the time I have lost and do not intend to try,” Agtuca told Judge Lasnik. “What I intend is to, for the rest of my days, commit myself to achieving balance.”