Locked up for three decades without a trial

A New York City man has been shuffled between Rikers Island and mental hospitals for 32 years.

Mario Ramos can’t remember much from his life before he was sent to Rikers Island. His brother Frank, visiting him in jail, tries to jog his memory, reminding Mario of the time they saw an Arnold Schwarzenegger movie together in 1986, just before Mario was arrested. But Ramos, a 60-year-old diagnosed with chronic paranoid schizophrenia, says he never saw it. He also has no clear memory of July 27 of that year—the day he allegedly shot three people in broad daylight in Washington Heights.

When Frank asks about that day, Mario gives contradictory answers. At first he says he somehow found himself in a building where someone shot at him. Then he says he was already at Rikers or “Mid-Hudson,” a reference to the Mid-Hudson Forensic Psychiatric Center, where he has received treatment. What Ramos can recall are scattered snapshots of the correctional and mental institutions where he has spent the majority of his life while awaiting trial.

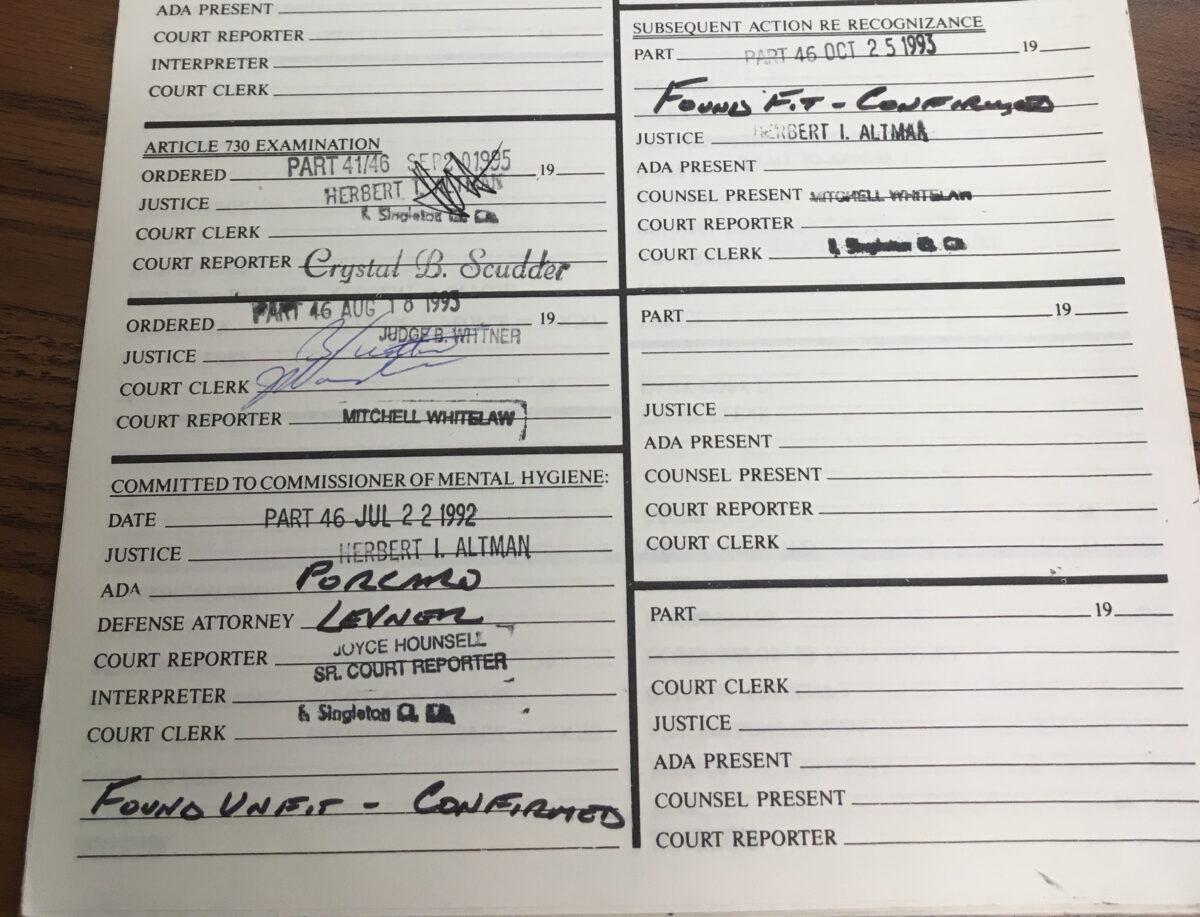

In a news account of the shooting, police noted that Ramos was incoherent and seemingly on drugs. A month after his arrest, Ramos pleaded not guilty. In January 1987, Judge Howard Bell ordered Ramos to undergo a competency evaluation. He was found unfit for trial, and the next month Bell ordered him moved from jail to a secured mental facility to see if he could be restored to competency. Ramos’s available case files do not make clear whether he was deemed competent for trial during this period. But by July of that year, Bell had ordered another mental competency test, triggering the whole cycle again.

Since Ramos’s arrest, eight judges have ordered at least 31 mental evaluations and multiple doctors have diagnosed him with chronic paranoid schizophrenia. Yet because his charges are so serious—initially for attempted murder and later for two intentional murders—Ramos cannot escape the criminal justice system.

Many states set a clear limit on the amount of time they hold people with mental health issues in jails and forensic psychiatric hospitals who have not been found competent to stand trial. But in some states, including New York, authorities can keep attempting to restore a defendant’s mental capacity until the person has served two-thirds of the maximum sentence he or she would receive if eventually found guilty. Ramos’s maximum sentence is life in prison, and so he sits trapped in Rikers, serving out two-thirds of his life, an unofficial sentence with no verdict and no certain end point.

The case is an example of how people with mental health issues can get lost in the criminal justice system, unable to undergo trial or receive permanent care in a civil institution. Ramos’s court-appointed lawyer is now attempting to get a judge to release him from criminal custody, arguing that despite being unfit for trial, his indefinite detention is a violation of due process. For Ramos to be civilly committed to a mental institution or to be released to his family, his attorney needs a judge to agree to a recently filed motion, which the Manhattan district attorney’s office could choose to fight at a hearing on Friday.

‘Sometimes people have to do something wrong to get help’

When he talks to his family at Rikers, Mario Ramos sits back or hunches over, yawning every few minutes. His sleepy eyes rest on his 84-year-old mother, Ita, who has driven from Rhode Island to see him. When Ita and Frank ask him questions, he speaks in quiet Cuban Spanish, never uttering more than a sentence or two. Asked about what he misses about the outside world, he says, “Nada.” His head droops as he speaks. When his brother asks him to explain, he responds, “Estoy aquí.” I’m here. His chin rests on the counter looking at us through the glass divider.

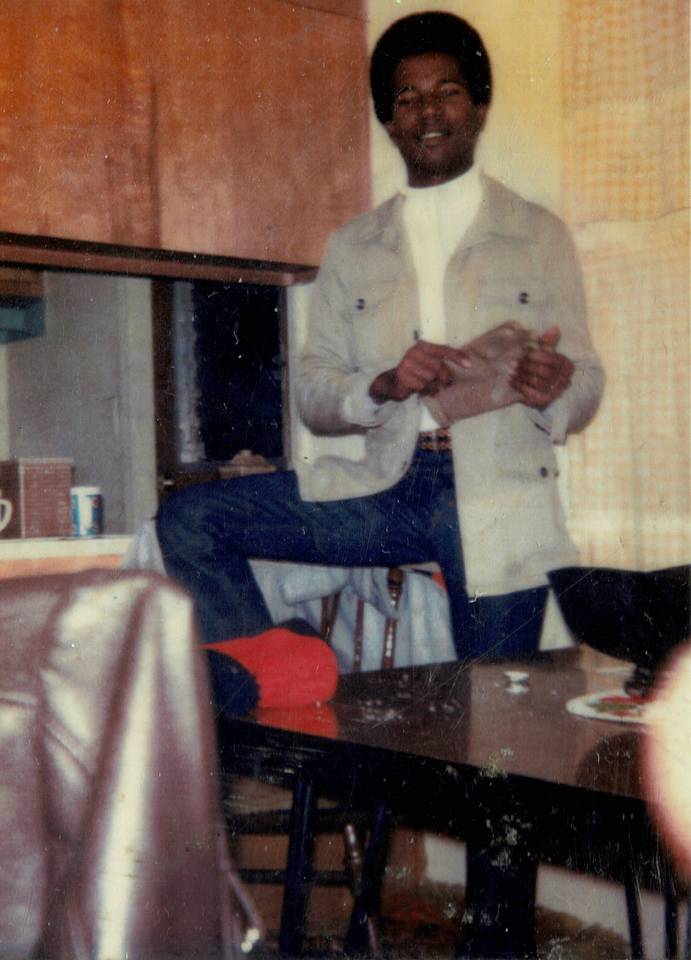

Ramos’s life wasn’t always like this. Along with his brother and his single mother, he came to the U.S. from Cuba by boat in 1980, looking for economic opportunity. Ramos bounced around the country, moving from Miami to New York to Rhode Island and back to New York over the next six years. His brother says it was hard for him to find work, not knowing English, and recalls him doing odd jobs to help provide for the family.

“He had to get a job at whatever he could, anything he could make money in, fixing roofs, painting houses,” Frank Ramos, 50, recalled of their time together in New York. “It was fun. My brother was always there caring for me. He used to take me to school. We used to play baseball and sometimes we used to play card games.”

Odd jobs alone weren’t enough to pay the bills, however, says Maira Soto, Mario’s girlfriend at the time. Soto says that around 1983, they moved from New York to Providence, Rhode Island, and Mario started selling drugs. “He didn’t have any other options. It’s very hard coming from Cuba in the 1980s,” Soto said in a phone interview. “No one wanted to give [us] a job because we [didn’t] speak English.”

“He did so much for me, buy me a car, buy me jewelry. In the ’80s, the money was flying off the street,” Soto said. But the couple soon fell into using cocaine themselves and Ramos’s mental health rapidly deteriorated, Soto recalls. “The mental health issues showed itself after the drugs. He would get violent, paranoid. Drugs made him think people were coming to get him.”

Soto and Ramos eventually moved back to New York, and Ramos resorted to petty crimes to feed the couple’s habit. He tried to sell drugs, but his growing paranoia made it difficult, she said. “Black people got the territory in Harlem; in Washington Heights, the Puerto Ricans wouldn’t let him join because they knew he was crazy,” said Soto, who said she left him in 1984 because of his drug use and occasionally violent outbursts. “He thinks everybody was out to get him.”

Frank Ramos was only a teenager at the time but sensed something was wrong. He said that in the weeks before the arrest, his brother sought help by going to a police precinct. “He said something bad was going to happen, so he wanted to turn himself in,” Frank remembers. “The police wouldn’t help him because he hadn’t done anything wrong. Sometimes people have to do something wrong to get help.”

‘How did it get to this point?’

On July 27, 1986, Ramos was found a few blocks from where a shooting had just taken place; a purse was found on the ground nearby. Police searched the purse and found a gun that matched the ballistics report of the bullets fired in the shooting.

A New York Times article about the incident said that Ramos “appeared to be under the influence of drugs” and shot at a man “for no apparent reason,” wounding two others in the process. Ramos was arrested, and soon more charges were brought against him. The prosecution determined that the gun found in the purse was also linked to a murder that took place on July 21, six days earlier. In November, he was indicted for a second murder, from 1982.

Lawrence Levner, Ramos’s original defense attorney until he died in 2006, argued that the charges should be reduced to manslaughter. Someone with chronic schizophrenia could not commit second-degree murder, he argued, which requires intentionality. But the charges were neither dropped nor reduced.

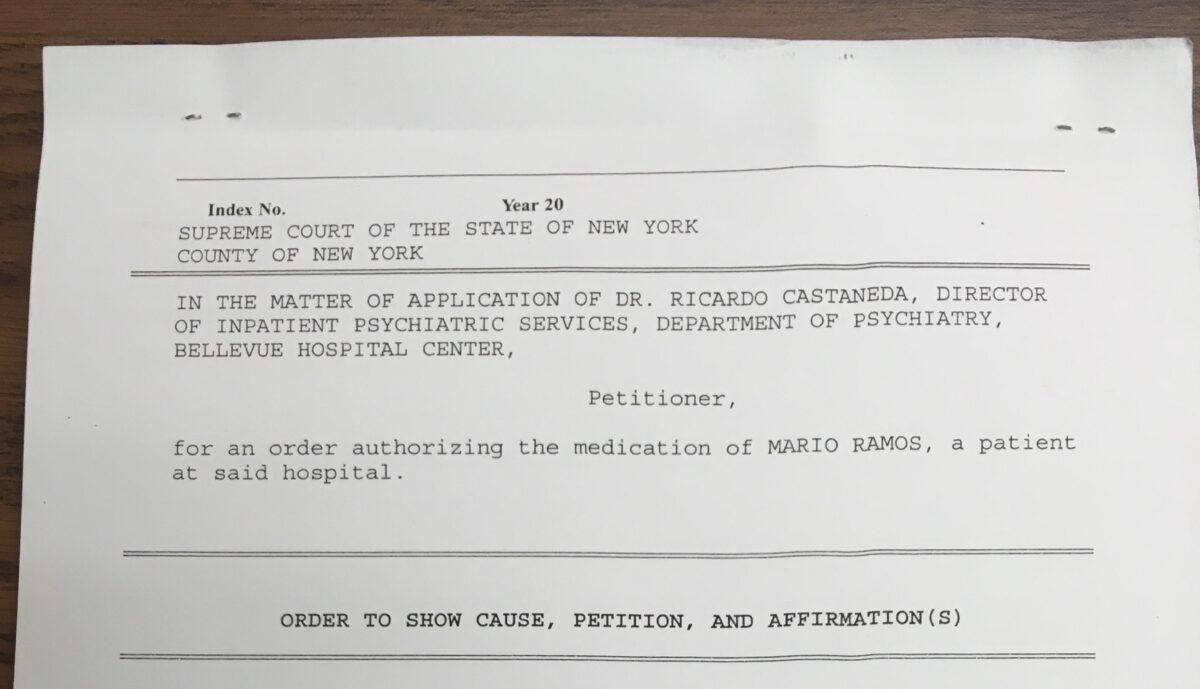

Despite repeated stints at mental hospitals, Ramos’s health never significantly improved in the decades that followed, according to court records. In a 1993 motion, for example, Levner pointed out that Ramos had gone through seven competency evaluations, all of which found him incapable of proceeding. One doctor who petitioned the court for permission to administer antipsychotic medication in 2004 testified that during a stint at Bellevue Hospital, Ramos was “unwilling to eat food because of delusions. He believes that as a ‘disciple of Christ,’ he doesn’t need food. He has disorganized thoughts and behaviors. He is not oriented to place, time, or person (he believes he is in China, and has another name).” Another doctor confirmed this, saying Ramos told him “he has never eaten food.”

During his decades in the system, Ramos has been evaluated at least 31 times and committed to mental institutions at least 29 times by judges. He or his attorneys have appeared in court more than 236 times, as Ramos has jumped between Rikers, court, state psychiatric facilities, and back. A handful of prosecutors have handled the case for the Manhattan district attorney’s office, including Patricia Nuñez, who took over the case in 1988 and prosecuted Ramos until 1997, when she was appointed to a judgeship in New York County Criminal Court.

When contacted by The Appeal, Nuñez remembered the case as unusually drawn out. “What happened over the years is that: I get ready for trial and he would then start acting irrationally, his attorney would ask for a 730 [New York’s term for a competency evaluation], he’d be unfit, go to Mid-Hudson, they’d put him on meds, he’d be fine, he’d go back to court, we start getting ready for trial again, and [while at Rikers] he’d go off his meds, he’d get 730’d, be unfit, go to Mid-Hudson, be OK on meds, but as soon as he comes back to court [and Rikers], he stops taking them. It was just a complete cycle. That’s what happened when I was handling the case. … When I left the office, someone else took it over and I don’t really know what happened to it after that.”

It’s not unusual for patients to resist taking psychotropic medication—and the state must meet a high burden before it can forcefully medicate someone with such drugs. Antipsychotic drugs can cause numerous side-effects, both physical and emotional, including chest pain, cardiac arrest, anxiety, confusion, and depression. In criminal psychiatric institutions, doctors can apply to courts to administer psychotropic drugs involuntarily to inmates. At Rikers, health authorities are not authorized to forcibly administer drugs, said Veronica Lewin, a spokesperson for NYC Health + Hospitals’ Correctional Health Services.

Ramos has been evaluated at least 31 times and committed to mental institutions at least 29 times by judges. He or his attorneys have appeared in court more than 236 times.

The case is now on the desk of Assistant District Attorney Kerry O’Connell, who has had it since 2004. When approached at a recent hearing on Ramos’s case, O’Connell told The Appeal, “You need authorization from my press office to speak with me.” The Manhattan district attorney’s office denied that request along with The Appeal’s request for information about the case.

Peter Zimroth, a longtime prosecutor who worked in the Manhattan district attorney’s office from 1975-80 said that given the seriousness of the charges brought against Ramos, “It’s something that the government isn’t going to want to just dismiss and send away without any kind of adjudication.” But, he adds, “When you look at it now, 32 years later, you look at it holistically, and say, ‘How did it get to this point?’”

He equates it to a plane crash. “If you research why a plane crashes, typically it’s not because of one thing. It’s almost always because of multiple errors, either human or mechanical.” It’s the same issue here, he said. “You need a lot of things to happen to get to the point where you have a case that’s 32 years old. … You have the passing of the baton of the case on all these different levels from the judge, defense attorney and prosecutor—they’re not necessarily errors, but it creates a situation where you can see something like this happen.”

Nuñez said, “The fact that it was a murder indictment [made it] difficult to try to offer him a plea bargain that maybe would have been acceptable to him,” she said. “A lesser case, a lesser charge, might have been more easily resolved with some kind of plea bargain that would have gotten him out of jail. But with a murder, that’s not really something on the desk.”

Defining a ‘reasonable’ period of time

In a recent op-ed, Alisa Roth, author of Insane: America’s Criminal Treatment of Mental Illness, reported that at any given moment, more than 40 percent of Rikers’s population is mentally ill, making it one of the largest providers of psychiatric care in the country. As of April 2018, she noted, in New York City, it took, on average, 43 days to complete an evaluation, and 186 people at Rikers were waiting for a mental health competency exam. Roth acknowledged that in recent years, Rikers has opened new mental health care units with specialized programming. These units have helped detainees take the medicine they need, and driven down self-harm and use-of-force incidents. But, she wrote, these units have far too little bed space for those on the island who are struggling with mental illness.

In an email to The Appeal, Lewin, the spokesperson for NYC Health + Hospitals’ Correctional Health Services, pointed to the agency’s recently announced plans to consolidate the management of its psychiatric evaluation court clinics in an attempt to cut wait times for detainees.

When asked about the quality of care people receive in civil facilities versus jails, Lewin said, “No level of care is superior to another—care is based on the needs of individual patients.” She noted that patients who need a greater level of care than they get in jails are transferred to psychiatric inpatient units “with dedicated psychologists, social workers, mental health clinicians, and psychiatric prescribers.”

But the frequent transfer of patients can wear on their health. In Ramos’s case, it has most likely hampered his ability to be restored to competency and go to trial, explained one Rikers employee, who requested anonymity because the person was not authorized to speak about the case. The added stress of the jail environment means that prisoners’ mental health issues can worsen upon their return to Rikers, even if they have improved to some degree after a hospital stay. In about 80 percent of felony cases, detainees who have been successfully restored to competency eventually revert to being found incompetent while held in the jail awaiting their next court dates, according to a 2012 Vera Institute of Justice study of Rikers detainees.

Going on and off medication, for instance, can exacerbate a patient’s illness. “While mental health staff are aware of this risk and attempt to mitigate repeated cycles to the hospital, Mr. Ramos’s case is an example that maybe these efforts have been exhausted,” the Rikers employee said. “Giving him Jackson relief would mean that he is released or in the hospital indefinitely, and not in a violent, notorious jail,” the employee said, referencing a judicial order that would remove Ramos from detention on the grounds that he will not become competent in the foreseeable future.

Ramos is far from the only defendant trapped in Rikers because of mental health issues, the employee said. “The fact that he’s been going back and forth so many times is a testament to the fact that people are falling through the cracks.”

New York’s failure to limit the amount of time certain defendants with mental illnesses can be held in jail and forensic institutions conflicts with the state’s constitutional obligations, defense attorneys argue. The 1972 U.S. Supreme Court decision Jackson v. Indiana found that courts can only keep people incarcerated for a “reasonable” period of time while they try to restore their mental competency for trial. The definition of “reasonable,” however, has been left to the states. A 2017 survey conducted by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors found that of 37 responding states, 11 said they would commit someone during competency evaluation for at most one year, eight have a limit of one to two years, six will commit someone for over three years and four said the time of detention depends on the sentence length or nature of the case itself (as in New York). Nine said they have no specific limit.

The fact that he’s been going back and forth so many times is a testament to the fact that people are falling through the cracks.

Anonymous Employee Rikers Island

State laws like New York’s, known as Article 730, which directly link the amount of time a defendant can be held during competency evaluations to the charges they face, seem to “stand just in complete contrast” to the Jackson decision, said Jenny Semmel, supervising mental health attorney for the Bronx Defenders. “Whether someone is charged with a robbery or charged with a homicide, it shouldn’t impact the question of whether or not they can be restored to competency. … I would argue that there’s due process, equal protection, all those sorts of issues that could be raised.”

Silvana Naguib, a defense attorney now based in California who has represented scores of clients with mental health issues, was shocked to learn of Ramos’s decades in and out of Rikers. “This strikes me as beyond absurd,” she said. “I would even say 10 years is absurd. To have three times that is unfathomable in its absurdity.” She questioned why prosecutors would continue to pursue the case and why judges would allow it. “You can’t continue detaining the person. There has to be reasonable confidence the person will be restored in the reasonably foreseeable future.”

The 2017 study found that competency evaluations have significantly contributed to a rise in the number of criminal defendants receiving inpatient services at state psychiatric hospitals. The study notes: “Some states are experiencing such a dramatic increase in forensic patients (in particular defendants requiring trial competency evaluations or competency restoration services) that their state hospitals are operating at, or close to, maximum capacity.”

The issue of how to handle defendants deemed incompetent may be coming to a head, explained Richard Cho, director of behavioral health for the Council of State Governments Justice Center. Officials may be “trying to do right by them by taking into account their mental health,” Cho told The Appeal, but the result can be prolonged pretrial detention. “Tying them up in the competency evaluation process often is just kicking the can down the road.” This not only jeopardizes their constitutional rights, he says, it also results in poor treatment for the patient and high costs for the state. States, he added, are “beginning to see how many resources and people are caught up in this competency evaluation process and how that bottleneck is not getting addressed.”

‘This is not a life’

Ita, Mario Ramos’s mother, wants her son to come home with her to Rhode Island, where his younger brother, Frank Ramos, is an elder care specialist and could watch over him. “This is not a life,” she says in Spanish, clutching her green and yellow Santeria necklace and looking around the bare waiting room after visiting Mario. “I don’t see the justice in the U.S.”

Ramos’s family members feel they have no say in whether he remains cycling in the system, is released to an institution, or is given back to them.

On May 18, Ramos’s attorney Michael Conroy filed a motion to dismiss the case and find Ramos permanently unfit for trial. “It seems clear at this point he’s never going to be fit,” the attorney told The Appeal in the hallway outside the courtroom. On Friday, O’Connell, the Manhattan prosecutor, will have a chance to concede the motion, or fight it.

Even if a judge does grant the Jackson motion in this case, Ramos could still be held involuntarily in civil commitment if authorities deem he poses a danger to himself or the public. If Jackson relief is granted, doctors for New York State’s Office of Mental Health would decide whether they want to try to hold him involuntarily, explained Michael Neville, director of New York’s Mental Hygiene Legal Service. If they decide civil commitment is necessary, the office would then apply to the court to retain him in a civil facility outside of Rikers, at first for six months, then for a year, then two years, as deemed necessary, he said. A defendant can challenge these decisions every step along the way, notes Neville, who points out that authorities sometimes use an expansive definition of what it means to be dangerous. “They could argue, for example, that provocative behavior in the outside world could cause others to fight them,” he said. “It can be very broad.”

Sitting across from his family at a table at Rikers, Mario Ramos laughs when he hears about the possibility of spending more years of his life in a hospital, even though he says it would be better than jail, where he says fights often break out. “No quiero ir pa’lla,” he says multiple times. I don’t want to go over there.

The Rikers employee argues that the case’s seemingly never-ending proceedings speak to a larger constitutional issue with New York’s treatment of defendants with mental illnesses. “The overarching issue is that he should have never been detained this long in the first place,” said the employee. “At this point, he’s not guilty of anything. Even if people aren’t sympathetic to his charges, we haven’t proven him guilty beyond a reasonable doubt in the first place.”

Even if Ramos did the crimes he has been accused of, 32 years of being held involuntarily in jail and mental hospitals is punishment enough, argues Ita Ramos. “What is the use of the justice system if you can never finish paying for the crime?”