Formerly Incarcerated Businessowners Sue SBA For Denying Them COVID-19 Emergency Loans

The lawsuit says the Small Business Administration overstepped its authority by imposing ‘arbitrary and capricious’ restrictions on a loan program passed by Congress.

A new lawsuit claims that the Small Business Administration is illegally barring some formerly incarcerated people from receiving emergency loans to address the economic impact of COVID-19 on their businesses.

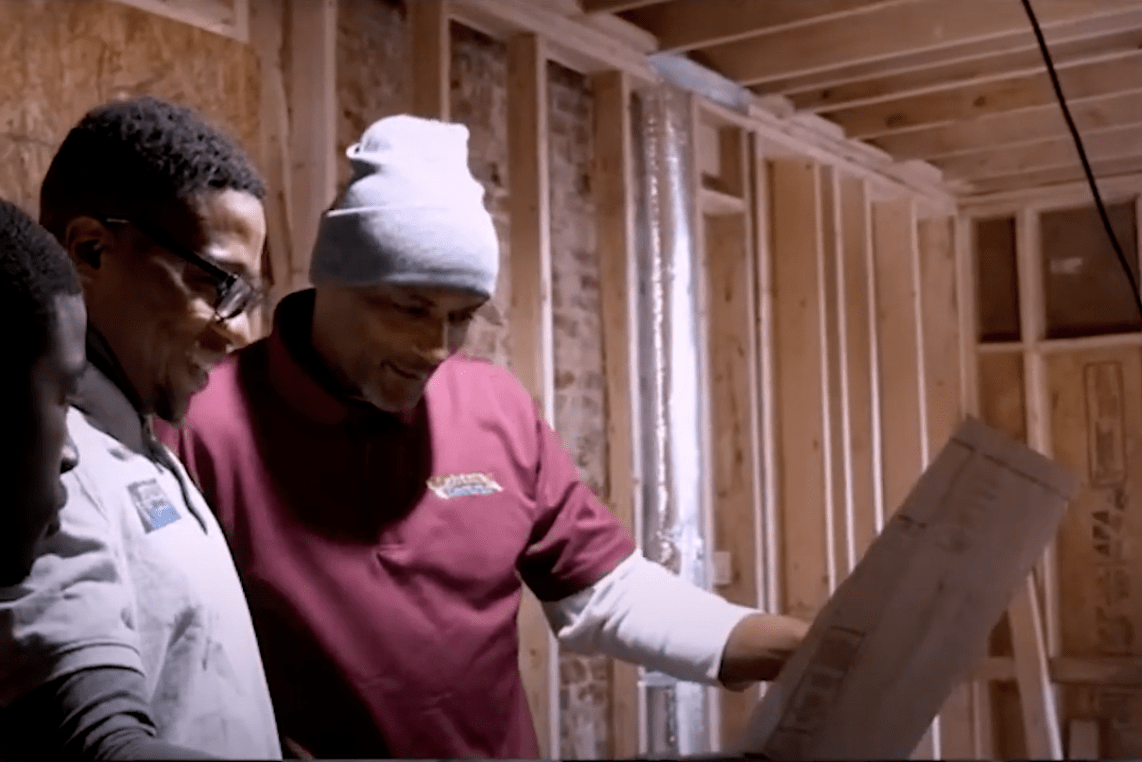

One of the plaintiffs, Sekwan Merritt, started Lightning Electric, an electrical contracting company in Maryland, in October of 2017, shortly after returning home from serving five years in prison after he pled guilty to non-violent drug offenses, according to the lawsuit filed Tuesday. He aims to provide electrical services to underserved communities, the suit notes, and he makes a point of hiring and training formerly incarcerated people; of the five electricians who work for him, four also spent time incarcerated.

But after Maryland Governor Larry Hogan closed non-essential businesses on March 23 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Merritt was forced to shut down his operations almost completely. The intermittent work he has been able to get isn’t enough to pay all of his employees. So when Congress passed the CARES Act on March 27 and created the Paycheck Protection Program, which gives small business owners forgivable loans to cover their payroll costs, he applied as soon as he could. He was hoping the money would allow him to pay his employees and other costs to keep everyone afloat.

Toward the bottom of the application, however, he encountered two troubling questions: Was he, the applicant, subject to criminal charges, currently incarcerated, or on probation or parole? And, within the last five years, had he been convicted of a felony, pleaded guilty to one, or placed in pretrial diversion or any form of parole and probation because of the felony?

Because Merritt is still on parole, he had to mark “yes” for both. As soon as he submitted the application, a screen popped up saying, “Based on the answers provided, your application cannot be processed at this time,” the lawsuit reads.

When Congress passed the CARES Act, it didn’t include any provisions indicating that people with criminal backgrounds should be excluded. And yet the SBA, which is administering the program, issued its own rules in early April, excluding any business owner convicted of a felony in the past five years from getting a loan, as well as those who have been charged but not convicted, and those, like Merritt, who are still on probation or parole.

Now, Merritt, along with another small business owner and a nonprofit, is suing the SBA and the Treasury Department, arguing that the exclusions are “inconsistent with the text and purpose of the CARES Act,” the complaint states. The SBA’s rules, the complaint reads, have been “arbitrary and capricious,” frequently shifting “without explanation or notice.” Both, the lawsuit alleges, violate the Administrative Procedure Act, which governs how federal agencies issue regulations.

In response to a request for comment, Carol R. Wilkerson, press director for the SBA, said, “SBA does not comment on pending litigation.” The Treasury Department did not respond to a request for comment.

The CARES Act stated that “any” business that satisfied the eligibility criteria—one with fewer than 500 employees and in operation during the covered period—“shall” be eligible. But the SBA went beyond its authority, said Claudia De Palma, a staff attorney with the Public Interest Law Center who is representing the plaintiffs along with the American Civil Liberties Union and the Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs. She added that “an agency must act with a rationale,” but the SBA hasn’t explained why it issued the criminal history rules.

Denying loans to people with criminal histories has serious consequences, De Palma noted. “It really is a question of financial life or death for these companies,” she said. And if they can’t afford payroll, their employees suffer. “The whole point of the money is to keep people paid,” De Palma said. “If they are barred from this money, that means that the people that work for them lose income.”

When it passed the CARES Act, Congress left some details for the SBA to clarify—for instance, how much of a PPP loan can be spent on things other than payroll. But “there were no blanks they were invited to fill in” on criminal history, De Palma said.

And while the SBA does include some criminal history restrictions in its other loan programs, these exclusions go much further. The 7a program, for instance, only outright bars people who are currently incarcerated, charged with a crime, or on probation or parole from receiving loans, but not those with closed prior cases. De Palma also argues that the PPP is an emergency grant program, different from a normal loan program, so these restrictions “are not a reasonable thing to import into the PPP.”

The issue has received some attention from Congress. The HEROES Act, passed in the House on May 15, would only bar those who were previously convicted of a felony for financial fraud or deception from the PPP, although it has yet to get a vote in the Senate. Separately, Republican Senators Rob Portman and James Lankford, and Democrats Ben Cardin and Cory Booker, introduced legislation on June 4 to remove the SBA ban on felony convictions.

On June 12, the SBA issued a revision that changed the look-back period for felony convictions from five years to one. But De Palma points out that the rule still bans anyone on parole or probation from applying for a loan. And even newly eligible applicants likely won’t know about the rule revision in time to apply by June 30.

“We feel that’s a really concerning way to operate when this money is so, so vital,” she said.

For now, Merritt is still excluded. His finances “remain highly precarious,” the lawsuit states, even as more work trickles in during the gradual state reopening. He’s poured his own savings and even money from family members into the company to try to keep it afloat, according to the complaint. But without financial assistance, his company may not survive.