Commentary

Joe Manchin’s Voters Aren’t Letting Him Stop $2,000 Checks

The intense backlash to his recent comments criticizing $2,000 stimulus checks signal the growing momentum for guaranteed income programs—and the emerging power of voters who care more about substantive results than partisan skirmishes.

On the same day President Joe Biden sketched out the first details of his $1.9 trillion COVID-19 stimulus proposal earlier this month, West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, a fellow Democrat, dunked its most important component in a bucket of cold water. “Absolutely not. No,” he told The Washington Post, when asked if the party’s top priority should be sending out $2,000 stimulus payments—a pledge that Biden, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, and a multitude of other Democratic politicians made repeatedly on the campaign trail. “Getting people vaccinated, that’s job No. 1.”

When the interviewer pointed out that this position placed him directly at odds with party leadership, Manchin more or less shrugged. “That’s the beauty of our whole caucus,” he said. “We have a difference of opinion on that.”

Manchin went on to explain that he might back a more narrowly targeted round of checks, if he could be persuaded that the money would bring back some of the millions of jobs that evaporated during the pandemic. Even under this hypothetical set of self-imposed conditions, though, he seemed to remain philosophically opposed to the notion of giving people money, and wistfully invoked the New Deal championed by President Franklin Roosevelt almost a century ago. “I don’t know where in the hell $2,000 came from,” Manchin later said, a statement that could only be true if he had not watched TV or listened to any member of his party for the last several months. “Can’t we start some infrastructure program to help people, get ‘em back on their feet? Do we have to keep sending checks out?”

For Manchin, this question is apparently rhetorical. For the 1.8 million West Virginians he represents in Washington, it is assuredly not. An infrastructure job soon is of little use to a family that needs to buy groceries last week. Already among the nation’s poorest states before the pandemic hit, more than half of West Virginians are now struggling to cover their basic expenses, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Since Manchin is the most conservative member of a Senate Democratic caucus that must remain united to act without Republican support, his opposition to sending out checks signaled to many that Biden’s proposal was effectively dead before members of the 117th Congress would even have the chance to vote on it.

Manchin’s constituents wasted little time expressing their feelings on the subject. The backlash was “swift and vocal,” said Stephen Smith, a former Democratic gubernatorial candidate and co-chair of West Virginia Can’t Wait. “People of all stripes and all over the state were saying, ‘This is the difference between whether or not my family gets to stay in their home. This is the difference between whether my small business gets to stay alive. This is the difference between whether or not I get glasses.’”

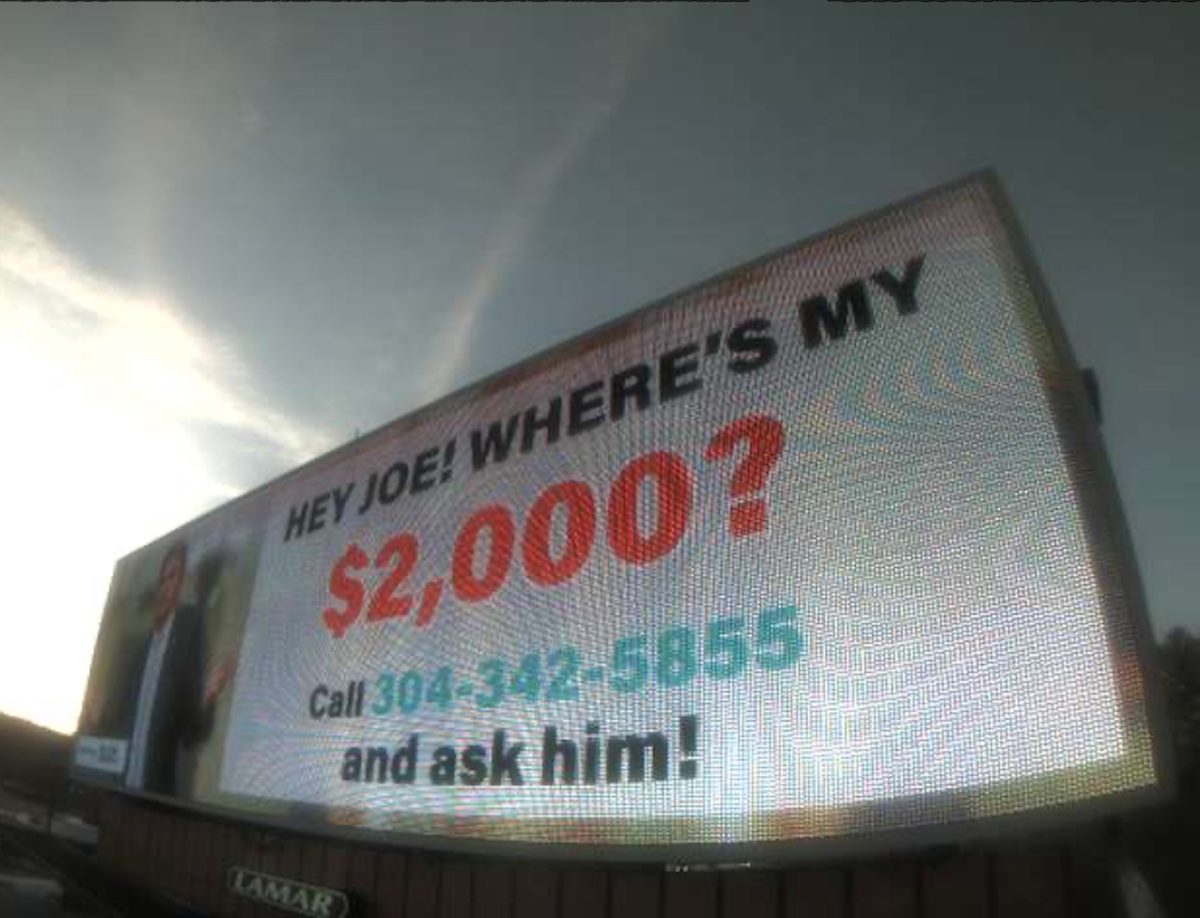

In Beckley, a billboard went up portraying a bewildered-looking Manchin next to “HEY JOE! WHERE’S MY $2,000?”—and, just as importantly, next to his office’s phone number. Radio ads mocked him for accomplishing the rarest of feats in Washington these days: being out of step on an issue with both Trump and his Democratic counterparts. “Our senator, Joe Manchin, thinks he knows better than both our president and the Democrats in Congress,” the narrator said. “I guess Joe just don’t know what it’s been like to live through the pandemic.”

“I think that it was important that we not equivocate on something that was core to the message that won us Georgia and the Senate,” says No Excuses PAC co-founder Corbin Trent, whose group paid for the ads that he narrated himself. “And not to look like Democrats, right out of the gate, are full of shit.”

The message, in some form or another, got through. During an appearance on Inside West Virginia Politics last weekend, Manchin again emphasized the importance of embedding trillions in infrastructure spending in a stimulus bill. But the precise distribution of direct payments, it seems, is no longer among his principal concerns. “Is there a way to target it? Maybe there’s not,” he said. “But we gotta get more money out.”

Manchin’s reversal here is a product of both West Virginia’s unconventional political landscape and the unique position he occupies within it. Voters in the state are less Democrat or Republican than independent and anti-establishment; although Trump won every single county in 2020 and beat Biden by nearly 40 points, registered Democrats actually outnumber registered Republicans, and nearly a quarter of voters are unaffiliated with any particular party. And after some four decades in state politics, Manchin is now the lone Democrat elected to statewide office, a skilled retail politician who prides himself on eschewing the labels by which many of his colleagues define themselves. (Re-elected most recently in 2018, Manchin was the only Democrat to vote to confirm Republican justice Brett Kavanaugh to the U.S. Supreme Court, and memorably made headlines by flirting with the idea of endorsing Trump’s re-election bid.) In an evenly-divided Senate, Joe Manchin’s penchant for refusing to toe the party line makes him arguably the most powerful lawmaker in Washington.

As the backlash to his comments illustrates, however, moderate politicians who overthink the inside-the-Beltway partisan machinations risk whiffing badly when it comes to delivering what voters actually want. Polling conducted by Data for Progress and The Appeal found that about 80 percent of all voters, including nearly three-quarters of Republicans, support a one-time distribution of $2,000 payments, and more than half support making such payments retroactive and recurring until the pandemic is over. As it turns out, the economic devastation wrought by a disaster that brought large swaths of American society to a grinding halt does not discriminate based on party preference. For lawmakers, performing bipartisanship when people are suffering doesn’t burnish your independent bona fides; it just makes your constituents furious.

With stakes this high, the emergence of independent, nonpartisan coalitions like the one banging on Manchin’s office door could redraw entrenched political battle lines in a hurry, even in this hyperpolarized version of Washington, D.C. “The thing that’s going to move Joe Manchin or anyone else positioning themselves on the fence … is the existence of a populist movement,” said Smith. “That is something that Manchin can’t control, and therefore has to listen to.”

Manchin’s objections to direct stimulus payments are as substantively unfounded as they are strategically unwise. For one, endless tinkering with eligibility criteria ignores the fact that the government has tools available to recover money that might flow to unintended beneficiaries—the annual tax filing process, for example. And although preemptive means-testing might sound like a sensible component of a massive cash distribution scheme, experts caution that it often does far more harm than good. “The moment you start to really apply means testing, there’s just a lot of people that fall through the cracks,” says Income Movement president and founder Stacey Rutland, whose organization paid for the billboard in Beckley. “Usually it’s the people who need it the most.”

The high-profile fights over COVID-19 stimulus payments have been a boon to the guaranteed income movement, which has already been the subject of high-profile pilot programs over the last several years. (A coalition of 34 mayors is now running ads in The Washington Post calling on Congress to make those stimulus payments a monthly occurrence: “ONE MORE CHECK IS NOT ENOUGH,” it reads.) Many people who were previously skeptical of “government handouts” now have firsthand knowledge of the woeful insufficiency of the existing social safety net. And the longstanding insistence on tying receipt of assistance to employment—a reliable staple of “welfare reform” language used by Republicans and Democrats alike—loses its rhetorical force when a global emergency prevents so many people from working at all. As Smith points out, the pandemic has not created economic precarity so much as it has democratized it. “People who are not sure how they’re going to put food on the table don’t need a crisis to remind them that things need to change in a fundamental way,” he says.

As Democrats in Washington prepare to tackle the stimulus bill—among the many, many urgent items on their agenda—conventional wisdom dictates that they have to act quickly to accomplish their legislative priorities, but also cautiously, to preserve the majorities that make those successes possible. The parties of incumbent presidents usually lose seats in Congress in the midterm election that follows. Given the narrow margins by which Democrats currently control both chambers, getting too ambitious might lose them the unified Democratic government they worked so hard to earn in 2020.

But Manchin’s rapid about-face here reveals just how shortsighted and obsolete this conventional wisdom really is. As Trent points out, Roosevelt, whose New Deal leadership Manchin cited approvingly to the Post, is the rare incoming president who actually expanded his party’s legislative majorities two years later. “It’s because they were producing,” Trent says. “That led to a generation of majorities and trifectas from the Democratic Party, and we were able to do some amazing shit because of that.” In this moment of crisis, voters are far likelier to punish their lawmakers’ failures to deliver than they are to reward knee-jerk partisan intransigence. Lawmakers who don’t learn this lesson will quickly find themselves out of office.

Jay Willis is a senior contributor at The Appeal.