Why Jails Are Key to ‘Flattening the Curve’ of Coronavirus

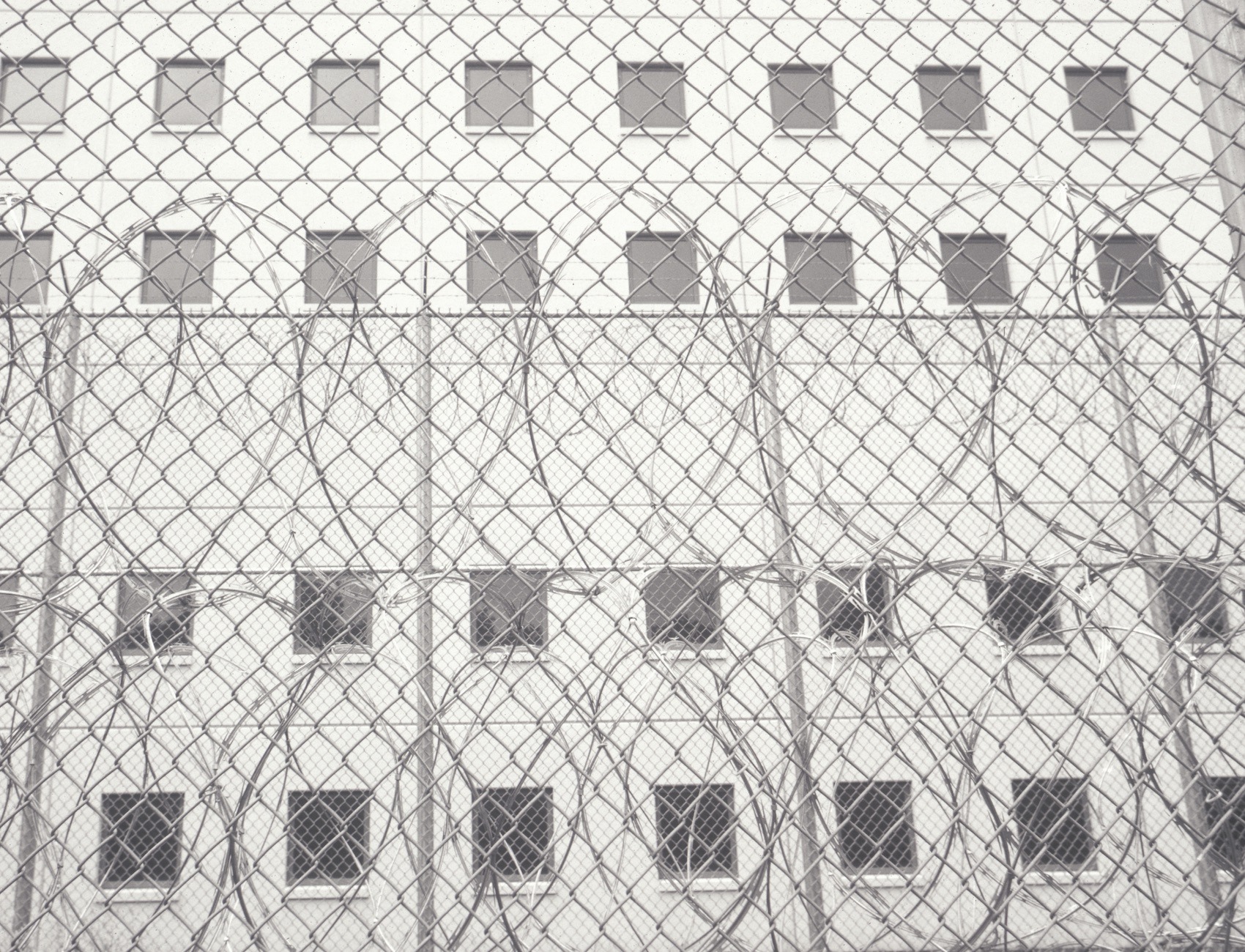

Local jails are notorious amplifiers of infectious diseases. If we don’t move quickly to reduce their population, it may undermine our ability to control the new coronavirus, nationally and locally.

This piece is a commentary, part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis on important issues and actors in the criminal legal system.

“Flattening the curve” so that the infection rate for COVID-19 stays below the healthcare system capacity is now critical to controlling the pandemic in the United States.

For individuals, that means cleaning your hands frequently and limiting social interactions. For governments and institutions, however, “flattening the curve” requires focusing on densely populated places whose inhabitants cannot isolate themselves. That is why the CDC has warned Americans not to go on cruise ships and why colleges across the nation are sending their students home even though few of those students are at risk of dying from COVID-19.

So far, however, we are ignoring what are probably the most important institutions that will undermine efforts to flatten the curve in every community: jails.

Jails are notorious incubators and amplifiers of infectious diseases. On any day, more than 600,000 people—roughly 75 percent of whom have not been convicted of a crime—are being held in one of our nation’s 3,000 local jails, most in congregate confinement, often in overcrowded conditions and with poor sanitation. What will happen when a new and poorly understood infectious disease makes its way inside a jail? It will likely spread like wildfire, not just among the people who live in the jail, but also among those who work there.

COVID-19 is also likely to be deadlier inside jails, where a greater share of the population has “underlying health conditions” than on the outside, including 7 percent with diabetes, 20 percent with asthma, 10 percent with heart-related problems, 7 percent with kidney problems, and 26 percent with high blood pressure. And because disease can spread quickly in crowded jails, they’re likely to produce large numbers of patients at once, overwhelming not just each jail’s primitive healthcare system but also hospitals to which the very sick and dying will be transferred.

So why should free people care that COVID-19 will spread faster and be more lethal inside jails than out? For those lacking in humanitarian impulses, the reason is that jails (unlike prisons) are revolving doors.

While fewer than one million people are in jail today, 10.6 million will cycle through them this year. Indeed, many people are there for only a few days—just long enough to catch the virus and take it home with them, if not to your neighborhood, then perhaps in line behind you at the supermarket or within six feet on public transit.

We can’t eliminate this problem, but we can greatly lessen it by drastically reducing the number of people in jail during this crisis. Courts have the power to do this by (1) releasing anyone who does not present a greater danger to themselves or others than they would if they were infected, and (2) by radically decreasing the number of people being sent there who don’t require immediate confinement. Each jurisdiction would need to develop its own criteria. Two easy ways to immediately reduce the number of people confined would be to release everyone who has fewer than 90 days left to serve, and most people who are in jail because they are too poor to make bail. Meanwhile, probation and parole offices can stop sending people to jail for “technical violations” such as failing to pay a fine, loss of employment, or a missed curfew, as opposed to commission of a new crime.

The only way to flatten the curve in this crisis is for society to act long before the infection rate surges. Immediately and drastically reducing jail populations might seem like an overreaction today. In just a few weeks, not doing it may be considered one of the great public health tragedies of our time.

Kelsey Kauffman is the founder and emeritus director of the higher education program at the Indiana Women’s Prison. She worked as a correctional officer at the Connecticut Prison for Women in the early 1970s and is the author of “Prison Officers and Their World” (Harvard University Press) and other studies of prisons.