‘It Tears Families Apart’: Lawmakers Nationwide Are Moving to End Mandatory Sentencing

Repealing state and federal mandatory minimums will help address the mass incarceration crisis, advocates hope.

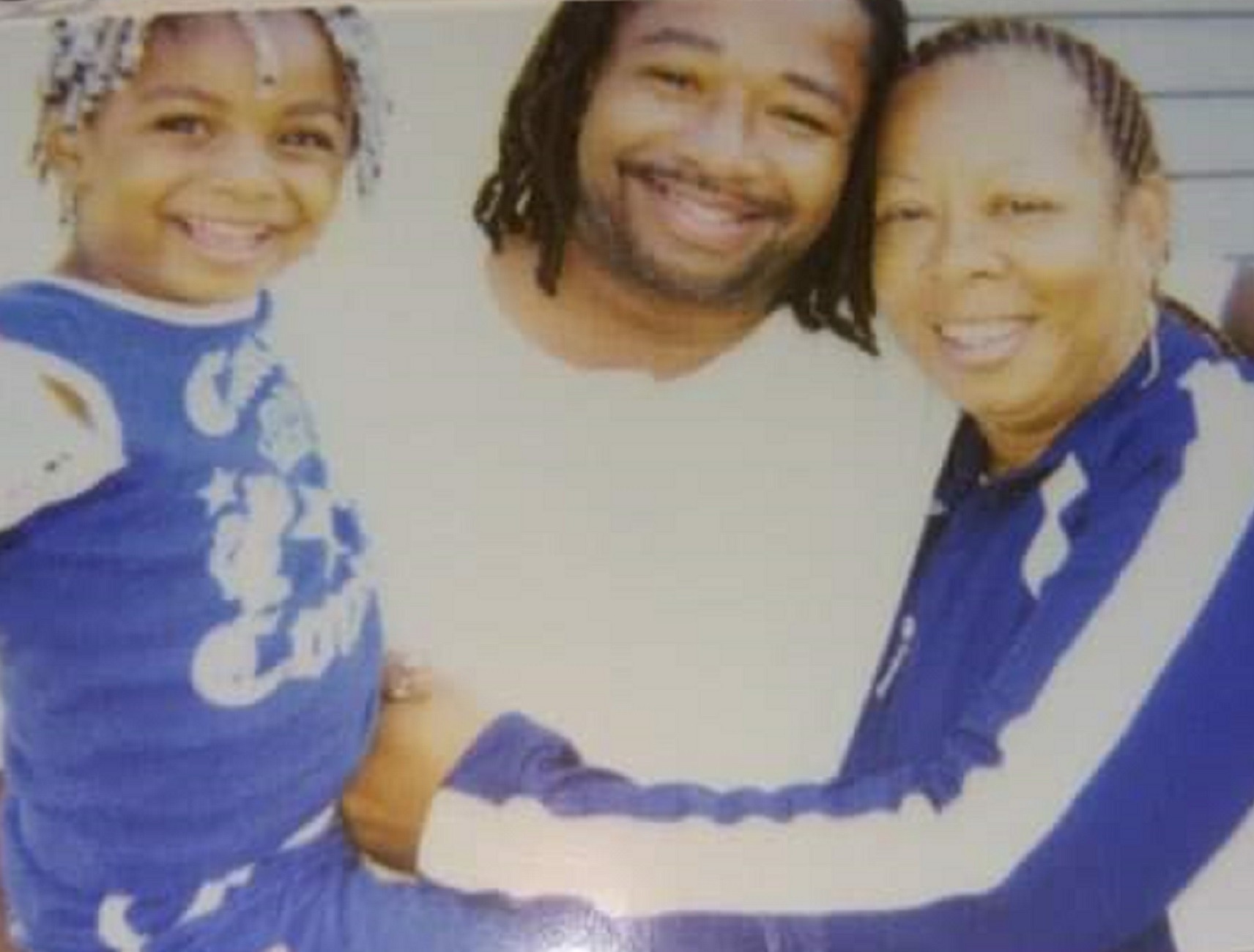

In 2002, Al-Tariq Witcher was sentenced to 20 years in prison, with a 10-year mandatory minimum, for drug and weapons offenses.

Witcher told The Appeal that at the time of his arrest a year earlier in Newark, New Jersey, he was struggling with substance use disorder and on the waiting list for a treatment program. His daughter was about three months old.

Once he went to prison, his mother brought his daughter to visit at least once a month. At the end of some visits, when she was barely a toddler, she grabbed onto him when she heard the announcement that visits were ending, he said.

“My mom used to have to pry my daughter off of me and my daughter’s screaming, hollering, ‘Daddy, Daddy, Daddy, I don’t want to leave,’” he said. When Witcher left to stand with other prisoners on the other side of a curtain he could still hear her crying for him.

“We need to go be strip searched to return to my unit,” he said. “She’s wailing and I’m on the other side. Tears are rolling down my cheeks.”

Witcher said he was released in 2011 after he was resentenced. He’s now part of a growing movement to eliminate mandatory minimums. Repeal of state and federal mandatory minimums will help address the country’s mass incarceration crisis and its catastrophic effect on Black people, according to criminal justice reform advocates. Earlier this year, Witcher testified in favor of Senate Bill 3456, which, if enacted, will eliminate mandatory minimums in New Jersey for certain nonviolent offenses. Lawmakers in several state legislatures, including Oregon, Virginia, and California, have introduced similar proposals.

There has been movement at the federal level as well. Last month, U.S. Senators Dick Durbin and Mike Lee reintroduced the Smarter Sentencing Act, which would reduce, but not eliminate, federal mandatory minimum sentences for some drug offenses. In January, President Biden’s Department of Justice urged federal prosecutors to use discretion in charging decisions and rescinded a Trump-era memo that required them to pursue the most serious charges available.

“Mandatory minimums, it tears families apart. My daughter was three months old when I got arrested. She was 9 going on 10, when I came home,” said Witcher, now an organizer with New Jersey Together, a community group championing S-3456. “Mandatory minimums are hurting Black and brown families.”

S-3456 passed the state legislature, but Governor Phil Murphy, who has had the bill since March 1, has not signed it nor has he publicly indicated if he intends to sign it in its current form. Murphy’s office did not respond to requests for comment. In public statements, Murphy has said he supports the recommendations made by the state’s sentencing commission to remove mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug and property crimes.

In New Jersey, a Black person is more than 12 times more likely to be imprisoned than a white person, according to a 2016 report by the Sentencing Project—the highest racial disparity rate in the nation. Eliminating mandatory minimums for certain nonviolent offenses will help reduce this disparity, according to the state’s sentencing commission’s 2019 annual report. The commission did not include data on the number of people serving a mandatory minimum sentence broken down by race, but it cited a National Academy of Sciences 2014 report that concluded racial disparities are “partly caused and substantially exacerbated” by mandatory minimums.

The New Jersey bill only applies prospectively, but if Murphy signs it, a second bill that would apply retroactively is expected to pass the legislature, explained Alexander Shalom, a senior supervising attorney at the ACLU of New Jersey. To help reduce the state’s prison population, the removal of mandatory minimums must be applied retroactively, said Shalom. But Shalom noted that of the more than 12,000 people imprisoned in New Jersey, most are being held for offenses that wouldn’t be eligible under a retroactive bill. S-3456, he said, should be “a first step in eliminating mandatory minimums, not a last step.”

“Mandatory minimums are bad public policy,” said Shalom. “We can’t stop with the crimes that have been called nonviolent.”

A proposal in California, introduced in December by state Senator Scott Wiener, limits repeal to nonviolent drug offenses. On Monday the bill passed the Senate and is now with the Assembly. “The War on Drugs has failed & has only led to mass incarceration,” Wiener tweeted. “Let’s stop criminalizing addiction & take a health approach to this problem.” South Carolina is considering similar legislation.

Discretion should not be limited to certain crimes, said Kevin Ring, president of FAMM (Families Against Mandatory Minimums). Ring said opposition to some but not all mandatory minimums comes down to people thinking, “I still want mandatories for this class of people that I think we need to be scared of or that I don’t have sympathy for.”

Oregon lawmakers proposed four separate bills that would reform Measure 11, a ballot initiative approved in the 1990s that requires mandatory minimum sentences for a number of offenses classified as violent, including robbery, rape, assault, and arson. Only one bill, Senate Bill 401, is still being considered. SB 401 eliminates mandatory minimum sentences for most Measure 11 offenses. For it to advance to the governor, at least two-thirds of each chamber must pass the bill.

However, because of Oregon law, sentencing reforms cannot be applied retroactively, explained Bobbin Singh, founding executive director of the Oregon Justice Resource Center, which is supporting SB 401. As of March 1, almost half of Oregon’s more than 12,000 prisoners were serving a Measure 11 sentence.

In addition to the bill’s potential impact, reducing the prison population, depends in part on prosecutors and judges, said Singh. Prosecutors will need to show restraint when making charging decisions and judges will need to depart from presumptive sentencing guidelines, he said.

“Optimistically, yes, it should reduce the prison population,” said Singh. “But it’s also completely dependent on the practitioners themselves.”

Before this year, repeal was considered nearly impossible, according to Singh. But the protests last year after George Floyd’s killing in Minneapolis changed that, he said. As of March 1, Black people make up about 10 percent of Oregon’s prison population that is serving a Measure 11 offense, but Black residents accounted for just over 2 percent of the state’s estimated population in 2019.

“Up until recently even bringing up the idea of Measure 11 repeal, it was the third rail. It was too big, too bold,” he said. “What’s happened around the racial justice conversation in the past year, that’s really created, and I think opened up, space for [a] Measure 11 repeal conversation.”

The Oregon District Attorneys Association opposes repeal, claiming that Measure 11 has not had a disproportionate effect on Black residents. In a report by the association, it cites a 2019 study by the Vera Institute of Justice that found that since the measure took effect, the white incarceration rate has increased while the Black incarceration rate has decreased.

“Measure 11 addresses conduct not color,” reads the association’s report on Measure 11. “While racial and ethnic disparities exist in the justice system and require attention, multiple independent studies demonstrate that Measure 11 has not contributed to racial and ethnic disparities in the prison population.”

But a report released last month by the state’s Criminal Justice Commission shows that between 2013 and 2018, a Black male in Oregon was more than four times likelier than a white male to be indicted for a Measure 11 offense. Black women were more than three times more likely than white women to be indicted for a Measure 11 offense.

Severe racial disparities around mandatory minimums persist in Virginia as well, where lawmakers this year considered, but ultimately did not pass, an effort to eliminate all mandatory minimum sentences.

As of June 30, 2019, 41 percent of Black prisoners were serving one or more mandatory minimum sentences, compared with 26 percent of white prisoners, according to a Virginia State Crime Commission report released in January. The commission recommended that the legislature eliminate all mandatory minimums. Virginia has more than 200 offenses that are subject to mandatory minimums.

“Thinking as a trial attorney how many people … I’m going to have this year charged with mandatory minimums who are either going to have to serve those sentences or going to be coerced into taking some kind of plea deal,” said Brad Haywood, the executive director of Justice Forward Virginia and the chief public defender for Arlington County and the City of Falls Church. “That’s going to be thousands of people in Virginia. … Mandatory minimums are going to affect their lives and they’re going to result in them serving unjust sentences.”

In February, Virginia’s Senate passed legislation to repeal all mandatory minimums. The House voted to eliminate mandatory minimum sentences only for certain nonviolent offenses. Ultimately, the two chambers couldn’t reconcile the differing versions.

But with momentum building to repeal mandatory minimums, the bill’s supporters say they plan to try again next session.

“We need to get rid of mandatory minimums,” said Jennifer McClellan, a state senator and gubernatorial candidate who supported the Senate bill. “It takes away the discretion for judges and juries to look at the circumstances of a particular case to figure out what is just and what punishment is proportionate.”