In 1 Day, New Mexico Prison Had 2 Suicides In Solitary Confinement

The state uses solitary at one of the highest rates in the nation.

Keith Kosirog hadn’t been convicted of a crime. But in early 2018, when he was charged with property damage and stalking, the state of New Mexico reviewed his history of mental illness and questioned his competency to stand trial. In July, a judge transferred him from county jail to state prison for “safekeeping.” There, he was placed in solitary confinement.

On Dec. 2, prison employees found him hanging in his cell from a yellow fabric noose. The guards, who the prison had said were supposed to give him “one-on-one watch,” hadn’t noticed when he’d killed himself likely hours earlier.

Roughly four hours later, a second man in solitary confinement at Central New Mexico Correctional Facility (CNMCF)—defined as 22 hours a day or more alone in a cell—also hanged himself. The state said the man, Adonus Encinias, had a medical condition that required him to be in isolation.

The two suicides are not surprising to Matthew Coyte, an Albuquerque-based civil rights attorney who has sued the state’s prisons over deaths in solitary confinement. Coyte pointed out that New Mexico has seen a high number of deaths in its jails and prisons.

“You’ll find that people in isolation are more likely to kill themselves,” he said. “Is this a crazy event? Well, no.”

According to the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics data from 2014 (the last time the agency issued a report on mortality in jails and prisons), 24 individuals died in New Mexico’s prisons that year and 10 died in local jails.

Our numbers of people in solitary have increased. They started climbing back up.

Matthew Coyte civil rights attorney

On Jan. 15, Kosirog’s wife and two children filed a lawsuit against the prison, its staff, and the healthcare company contracted with the facility, claiming they disregarded his history of mental health issues when they chose to house him in solitary without monitoring.

“Given CNMCF’s history of suicide, and the suicide rates in prisons, CNMCF should have known or knew and should have been trained to recognize the significant suicidal risk factors displayed by Mr. Kosirog,” the complaint says.

According to the lawsuit, Keith Kosirog had a traumatic childhood. He watched his father kill his mother and her boyfriend when he was 3 years old and at age 4, he testified against his father in court. His family also had an extensive history of mental illness. One of his sisters died by suicide and another sister attempted to kill herself.

His brother, Ken Kosirog told local reporters that Keith suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder after tours with the Marine Corps in Iraq, Haiti, and Kosovo. “From 2006 to present time, he was deteriorating,” Ken said. Since 2011, Keith had been hospitalized a number of times and had been given one-on-one monitoring as a suicide precaution. He told clinicians that he had attempted suicide at least 14 times.

The New Mexico Corrections Department declined to comment on pending litigation.

Thwarted reform

Someone like Kosirog should never have been in solitary confinement, Coyte said. Research shows that individuals in solitary are seven times more likely to hurt or kill themselves than those in the general population in prison. For those with mental illness, isolation exacerbates symptoms and often cuts them off from necessary mental health care.

Yet New Mexico uses solitary confinement at one of the highest rates in the nation. As recently as 2015, almost 10 percent of its prison population was in solitary.

In an effort to bring reform to the state, Coyte helped Democratic lawmakers write a bill two years ago that would have barred prisons and jails from housing individuals with mental illness and minors in solitary confinement for longer than 48 hours. The proposal passed both chambers of the legislature, but was vetoed by then Governor Susana Martinez, a Republican, in April 2017.

Martinez justified her decision at the time by saying that the bill “oversimplifies and misconstrues isolated confinement” and leaves prison officials with fewer options, endangering corrections officers and prisoners.

While most states house mentally ill individuals in solitary, a number of states have made efforts to reduce the practice. In 2014, Colorado passed a law mandating that mentally ill prisoners are sent to treatment instead of isolation.

Representative Antonio Maestas and Senator Mary Kay Papen, the sponsors of the bill, plan to reintroduce it this week and are hopeful for its success under the state’s new Democratic governor.

“We’re more optimistic it will pass, but there’s no certainty in these things,” Coyte said.

Widespread deaths in solitary

In 2015, New Mexico’s Corrections Department touted the fact that it had reduced its population in solitary confinement from over 10 percent to about 6.6 percent. But the change didn’t last long.

In 2016, the Corrections Department chief stepped down and issues returned. The department began dealing with staff shortages, and amid nationwide prison strikes, the state issued rolling lockdowns. When a facility is in a lockdown, individuals are held in isolation to ease the burden on staff.

“Our numbers of people in solitary have increased,” Coyte said. “They started climbing back up.”

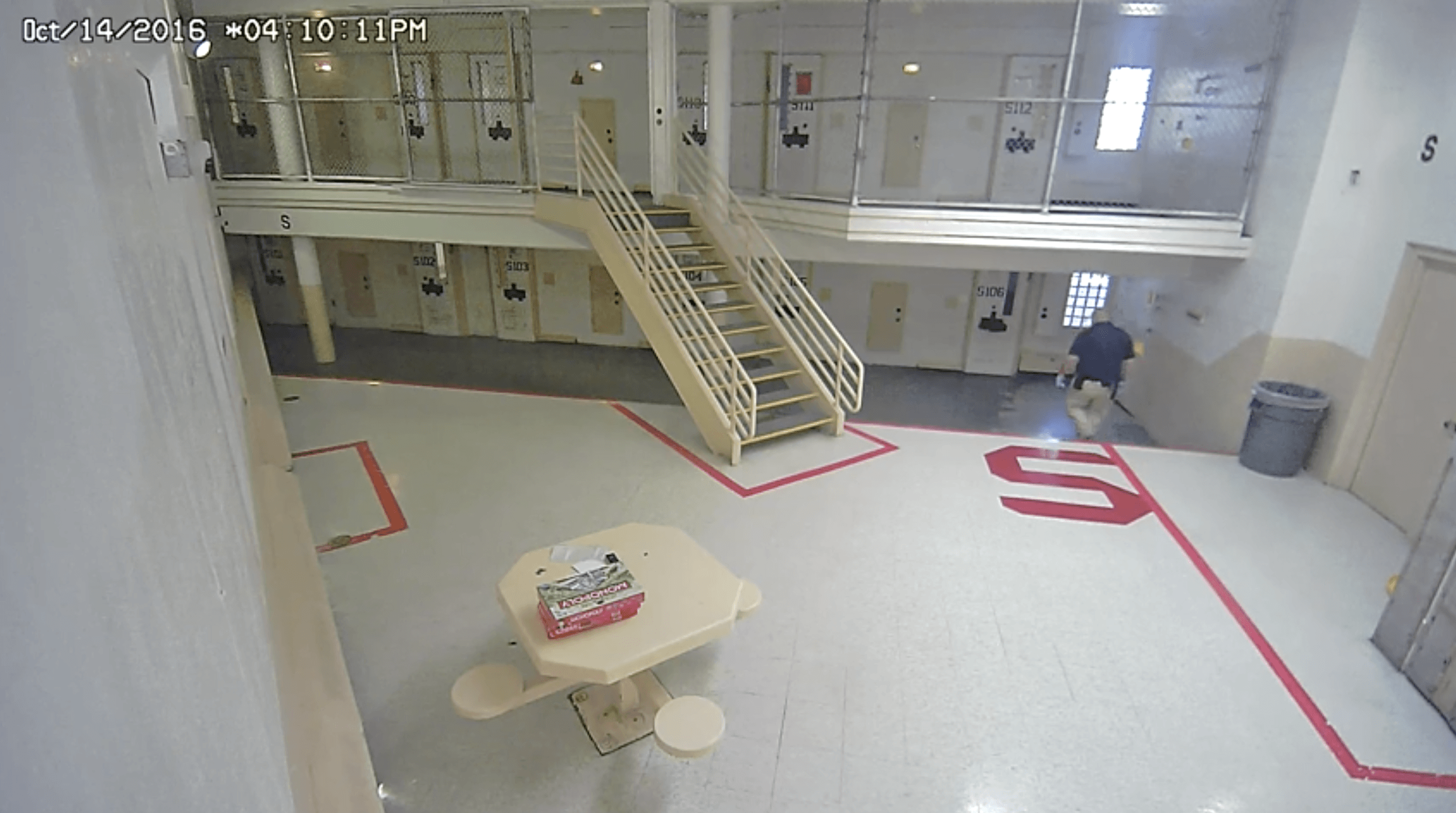

Around that time, in October 2016, guards found 36-year-old Francisco Luevano dead in his cell in the maximum security Penitentiary of New Mexico. His body had developed rigor mortis, meaning he had most likely been dead for hours, even though guards were supposed to check on him every 20 minutes. Coyte, who is representing Luevano’s mother in a lawsuit against the state, shared video with The Appeal showing guards passing Luevano lunch through a slot in the door. His tray is left untouched. He was found dead in his cell several hours later.

The autopsy report did not determine any cause of death. Luevano’s mother, Jonella Luevano, told The Appeal that explanation makes no sense. “I’ve never heard that anybody dies from nothing,” she said. “Have you?”

At the time of his death, Jonella had no idea her son was in solitary. She said he had no history of mental illness and she doesn’t understand how or why a healthy 36-year-old man would be found dead. Coyte filed a lawsuit in December 2017 under New Mexico’s Inspection of Public Records Act, seeking documents that would help explain why he died.

‘Safekeeping’

Coyte said he and other civil rights attorneys have targeted New Mexico’s county jails that use solitary confinement, filing lawsuits to get them to cut back on the practice. In many places, they have been successful.

But Coyte described that success as a “Catch-22.”

When a county jail receives an individual with mental illness, they are now more likely to transfer that person to the state prison system for “safekeeping.” Prisons, meanwhile, have policies that they do not allow pretrial detainees to mix with people who have already been convicted, Coyte said. That means that anyone with mental illness who is transferred to prison is housed in solitary confinement.

That’s exactly what happened to Kosirog, and how he ended up killing himself in a prison cell before he had been convicted of a crime.

“By trying to fix the problem,” Coyte said, “they’ve made it worse.”