ICE-friendly Policies. A String of Jail Deaths. Why Does This Sheriff Keep Getting Elected?

Advocates say Alameda County Sheriff Greg Ahern is an odd fit for the Bay Area, but mounting a challenge has proved daunting.

When Barbara Doss went to claim her son’s body last June, his face was covered in bruises. “The left side of his skull was busted open,” she said, with “staples holding it together.” He had multiple abrasions on his lips and dark bruises on his cheeks.

Her son, Dujuan Armstrong, died soon after reporting to serve the weekend at Santa Rita Jail in Dublin, California. More than seven months later, Doss still did not know how her son died, who was at fault, or who, if anyone, would be held accountable. So in January she traveled from Oakland to Sacramento to confront Alameda County Sheriff Greg Ahern, whose office runs Santa Rita, and who was due in the state capital to preside over a lottery commission meeting.

“I don’t have any answers. I need answers,” she pleaded. “I need to ease my mind.”

Her voice was assured but uneven as she fought back tears. “My son was 23 years old,” she told Ahern. “He left behind a whole family and friends. Not just his mother. Everybody. He has children, understand me?”

Armstrong’s death was not an isolated incident in Alameda County. Three days after he died, another man died while alone in his maximum security cell. According to the sheriff’s office’s own data, 80 people have died in Ahern’s custody since he took office in 2007, a number that includes 18 suicides and 14 deaths ruled accidental. Most of the deaths were natural, Ahern pointed out, and there have been fewer in recent years. Yet between 2015 and 2018, Alameda County paid $4.6 million to resolve lawsuits arising out of five in-custody deaths.

Doss demanded her son’s personal belongings and his autopsy report. She also asked to see body camera footage that, according to officials, shows Armstrong acting “agitated, aggressive, and uncooperative” and saying he was under the influence of cocaine, marijuana, alcohol, and prescription pills, before he was restrained and fell to the ground and stopped breathing. She wanted to know if the deputies involved were still on the job.

Ahern confirmed that the deputies were still working but said no other information could be released, citing an ongoing investigation by the district attorney. (A spokesperson for the sheriff’s office declined to comment further, but told The Appeal that more information would be shared when the investigation is complete.)

Before Ahern walked away, Doss asked him a different question, one that more and more people in Alameda County have been asking about the sheriff, who was recently elected to his fourth term: “Why are you the only person on the ballot?” she asked. “That’s what I want to know.”

A ‘cop’s cop’

Greg Ahern joined the Alameda County sheriff’s office in 1980, climbing the ranks until 2006 when his predecessor, Sheriff Charlie Plummer, announced his retirement and anointed Ahern to run the office. “Quite frankly, I don’t care who would run against Greg Ahern, because they’d lose,” Plummer said at the time. For the last 12 years, Ahern has overseen a sprawling county agency that today has a $444 million budget and 1,000 sworn peace officers providing court security, patrolling the county’s unincorporated areas, and operating the county’s two jails, including Santa Rita, the fifth-largest jail in the country.

Square-jawed and gruff voiced, Ahern is the stereotypical no-nonsense American lawman—a “cop’s cop,” as the president of the county Deputy Sheriffs’ Association said after Ahern’s first election—with a record of conservative policies and aggressive law enforcement. He has been a leader of the California State Sheriffs’ Association (CSSA), a powerful lobby that has opposed criminal justice reform and legal protections for undocumented immigrants. Ahern served as CSSA president in 2013 and has been chairperson of the CSSA Political Action Committee since 2010. In 2016, Ahern endorsed then-Senator Jeff Sessions to be U.S. attorney general, fueling sentiment among local activists that he is anti-immigrant and complicit in the Trump administration’s agenda to deport more people from county jails.

Ahern seems an odd fit for a diverse and deep-blue county that’s home to progressive strongholds like Berkeley and Oakland. County voters not only tend to elect Democratic candidates by enormous margins (Hillary Clinton won 78 percent of the presidential vote in 2016), they directly support criminal justice reform. The county overwhelmingly endorsed recent ballot initiatives to soften California’s “three strikes” sentencing law and expand parole eligibility for people with nonviolent felony convictions. The CSSA, on the other hand, opposed them both.

Through four election cycles, there has never been a single candidate willing to challenge Ahern at the polls.

This disconnect has not gone unnoticed. Reverend Michael McBride, who advocates for criminal justice reform in Alameda County as director of the Live Free Campaign, describes Ahern as a “respectable version of Joe Arpaio from Arizona,” the longtime Maricopa County sheriff infamous for rampant racial profiling and prisoner abuse. McBride said it’s “an indictment of the electorate of this region who claim to hate Donald Trump and his policies but will hire a sheriff who will work with him and Jeff Sessions to operate the deportation machine of this country. The contradictions of this region are too hard to fathom.”

McBride is among a coterie of local advocates, organizers, and community leaders who consistently target Ahern with their advocacy efforts. They see Ahern as a rogue actor who evades meaningful accountability, both from voters and from other government officials, especially the Alameda County Board of Supervisors. They have pushed Ahern with protests, demonstrations, and campaigns. They have organized town halls and made demands at public meetings. They have held vigils for those, like Dujuan Armstrong, who went to jail and did not make it home alive.

But through four election cycles, there has never been a single candidate willing to challenge Ahern at the polls. In 2018, Ahern ran unopposed and won another four-year term with 95.8 percent of the vote.

Dozens of lawsuits

Complaints against Ahern and his office run the gamut of law enforcement misconduct: prisoner abuse, excessive force, inadequate medical care, squalid jail conditions, anti-immigrant practices, and a still-unfolding scandal in which one deputy was caught on video admitting that he illegally recorded conversations between detained youths and their lawyers. Between 2015 and 2018, 41 civil rights lawsuits against the office cost Alameda County $15.5 million in settlements and judgments—the highest amount incurred by any Bay Area law enforcement agency during that time, according to the East Bay Express.

Allegations in some recent lawsuits depict a jail system that punishes rather than treats prisoners who need medical care. Mentally ill prisoners who say they were denied treatment and locked in isolation cells. A prisoner tased and beaten to death while suffering alcohol withdrawal. Women reportedly pressured to get abortions, and one woman forced to give birth on the cold concrete floor of an isolation cell in Santa Rita. (A sheriff’s spokesperson acknowledged at a press conference: “That incident actually did happen.”)

In 2015, 24-year-old Mario Martinez died in Santa Rita during an asthma attack. Martinez had secured two court orders to treat nasal polyps that obstructed his breathing, followed by orders to show cause why the treatment was not provided. A local television station’s investigation into his death revealed that the county’s private correctional healthcare provider at the time, Corizon Health, had secured three no-bid renewals of its county contract while also donating $110,000 to Ahern’s campaign. The board of supervisors approved the no-bid renewals at Sheriff Ahern’s written request. In an email, Ahern told The Appeal that “the contributions from Corizon were for a golf tournament that was for charity and not a conflict of interest.”

Asked about the allegations of abuse and neglect, Ahern denied that jail conditions in Alameda County are inadequate or that jailhouse deaths are taken lightly. He specifically disputed reports that mentally ill prisoners were denied treatment and said in the email, “We have never pressured inmates to get an abortion.” Regarding the woman who gave birth in her cell, Ahern said he couldn’t comment but that his office had denied any wrongdoing. He emphasized that his inmate population consists of “high risk” individuals “that have serious medical issues and problems with substance abuse when they come into our custody.”

In the past, however, he has disparaged and questioned the motives of prisoners who filed lawsuits: “You mean the people who are in custody for murder, rape, and robbery,” Ahern said in November 2018, “and who have lied their entire lives? We deal with people who don’t always tell the truth. That’s why this is called jail. … People are trying to get financial gain on things we don’t think are true.”

Working with ICE

More than any other issue, though, Ahern’s record on immigrant rights has incited opposition. Ahern “has continually opposed protections for undocumented immigrants,” said Yadira Sanchez, an organizer with the California Immigrant Youth Justice Alliance. She blames him for what she calls the “criminalization of undocumented immigrants in Alameda County.”

In 2008, Ahern’s campaign donated $1,000 to support Proposition 6, a California ballot initiative that would have, among other things, prohibited releasing undocumented immigrants on bail or their own recognizance before trial if they were charged with a violent offense. Seventy-three percent of Alameda County voters rejected the failed measure.

Ahern and the CSSA have also fought state sanctuary laws that prohibit local law enforcement from cooperating with federal immigration officials. For years, including while Ahern served as president, the CSSA helped block the California Trust Act before it was ultimately signed in late 2013. That law prohibits sheriffs from detaining undocumented immigrants at ICE’s request.

We have a rich history in Oakland of championing civil and human rights, but we have a sheriff’s department that’s not consistent with that, who dismisses people’s humanity.

Jose Bernal Ella Baker Center for Human Rights

The CSSA also opposed Senate Bill 54, legislation signed in 2017 that bars jail officials from providing ICE with information about a person’s release date. Before SB 54, Ahern’s policy was to provide release-date information to ICE on demand and allow deputies to share such information even when it was not specifically requested. In November 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced a $1 million grant to Ahern’s office under a federal program that prioritizes law enforcement agencies that cooperate with ICE.

In the last year, immigrant rights advocates have accused Ahern of creating a “loophole” in SB 54 with a new policy to publish the release dates of all prisoners on the office’s “inmate locator” website while allowing ICE to execute arrests in non-public parts of the jail. Sanchez said last year that this policy is “further indication that Sheriff Ahern and his department are continuing to side with the Trump administration … and seizing the moment to collaborate with ICE.”

Ahern has said the new policy is for the sake of transparency and unrelated to immigration enforcement. “The Alameda County Sheriff’s Office does no immigration enforcement,” he told The Appeal. “We follow state laws that pertain to undocumented individuals” and “we have an SB 54 compliance review that closely monitors any and all contact with ICE to make sure we are following the law and are protecting the rights of those in our custody.”

The search for a challenger

In 2017, frustrations over these and other issues sparked parallel efforts to force change on the sheriff’s office. One, a very public, ongoing campaign to audit the sheriff’s growing budget; the other, a behind-the-scenes endeavor to remove Ahern from office altogether.

In November 2017, the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights and the Justice Reinvestment Coalition of Alameda County launched the #AuditAhern campaign, asking the county board of supervisors to perform a complete financial and performance audit of the sheriff’s budget and practices. The group questions why the sheriff’s budget has increased by $146 million over the last 10 years despite significant drops in jail population, and fault the board of supervisors for a lack of oversight.

“We have a rich history in Oakland of championing civil and human rights, but we have a sheriff’s department that’s not consistent with that, who dismisses people’s humanity,” said Jose Bernal, a senior organizer and advocate at the Ella Baker Center. Bernal says the audit is the first step toward reinvesting dollars currently controlled by Ahern into the community.

Sanchez of California Immigrant Youth Justice Alliance agrees. “We have a housing crisis. We know that mental health treatment is not accessible to undocumented communities and is so badly needed,” she said. “If we could use [Ahern’s] millions for community alternatives to policing and incarceration, that would alleviate a lot of daily struggles that undocumented people see.”

Sheriff Ahern told The Appeal that there are several reasons for the increased budget, including increased staffing and compensation, rising “costs of doing business,” and more prisoners who need “special handling.”

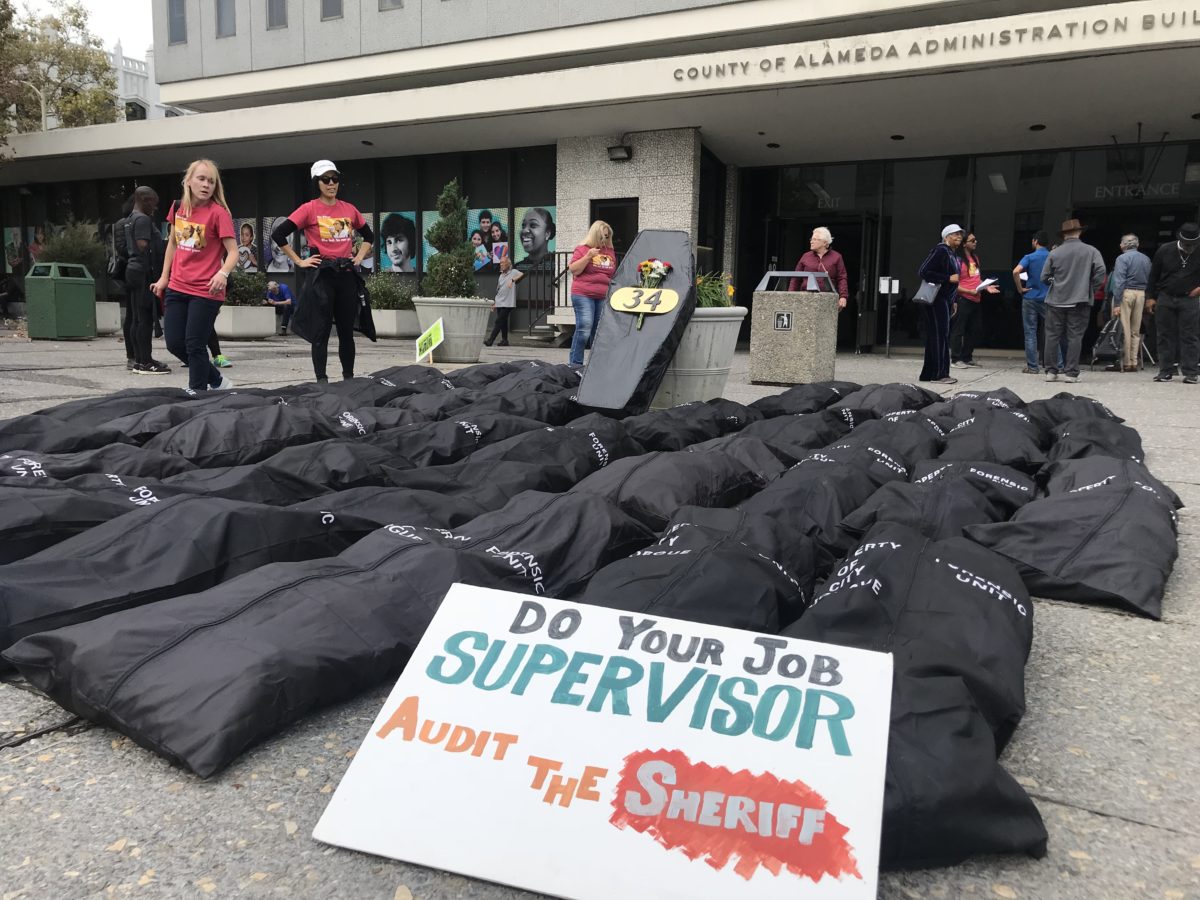

Bernal and others have kept sustained pressure on the board, writing op-eds like one this reporter helped research, organizing public comments at board of supervisor meetings, and staging high-profile actions, like marching with 34 body bags, one for each in-custody death in the last five years, from the county’s Glenn Dyer jail to the county administration building. But while the Berkeley City Council supports calls to audit Sheriff Ahern, the county board of supervisors has yet to agree.

“Right now there is a lack of political will on the part of the supervisors,” Bernal said. (County supervisors either declined or did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

By the time #AuditAhern became a unifying hashtag among county progressives, the most serious effort yet to recruit an election challenger was well underway for the June 2018 primary.

In early 2017, Nayeli Maxson had just been elected political director of the East Bay Young Democrats, and sanctuary policies for Bay Area cities was a frequent topic at policy meetings. “One piece that kept coming up is, well, Ahern isn’t the type of leader that you expect to or want to see in this progressive stronghold,” Maxson recalled. “A number of us kept asking, why? Why is he still here and why does he keep running unopposed?”

Working in her personal capacity, Maxson started to build a network of like-minded people, drawing from the deep pool of advocates who have been on Ahern’s heels for years. With a Facebook page and an email listserv, the Alameda County Coalition for a New Sheriff in Town was born. A research committee figured out the legal requirements to run, and the group started to build a list of names. Rev. Damita Davis-Howard of Oakland Rising Action called it “the first real effort that actually got beyond folks talking philosophically about seeking other candidates.”

But the group quickly hit snags. The first was California’s eligibility law. Sheriff candidates must have either an advanced certificate from the state’s Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, or a certain combination of education and law enforcement experience. The law, enacted in 1988, was devised by a subcommittee of the California State Sheriffs’ Association. Before then, the only requirement was that a candidate be registered to vote in the county.

This eligibility requirement, the coalition found, creates two barriers to a more progressive sheriff. Most obviously, candidates must come from a traditionally conservative field that many communities seeking reform have grown to distrust. “How can we find candidates that reflect our values?” Rev. McBride said. “Even though we’re considered progressive, the pool of potential candidates shrinks considerably because the position is understood as tough on crime, anti-Black, and designed to keep the system intact and not to be transformative.”

It also means that potential candidates are vulnerable to retribution from law enforcement leaders, jeopardizing their professional futures. “People would say, ‘I want to have a career ahead of me,’” Maxson said of promising candidates who declined.

In all, Maxson’s group identified about 10 eligible candidates. Most quickly said no. But one in particular, Sheryl Boykins, an African American woman who was then chief of a local university police force, expressed interest. After four or five meetings, she gave Maxson permission to start circulating her name as a potential candidate. “Oh, my God, we actually have a candidate and she’s amazing,” Maxson thought.

But the would-be campaign ended before it started. Before the filing deadline, Boykins declined to embark on an expensive countywide campaign against the entrenched, well-connected incumbent. (In January 2018, Ahern’s campaign reported over $245,000 cash on hand.) She retired instead, according to the university. Boykins declined to answer questions about her decision.

If you want to defeat an incumbent sheriff in 2022, the work needs to start now.

Nicole Boucher California Donor Table

Nicole Boucher is co-executive director of the California Donor Table, a community of political donors who invest in electing people who represent the values and needs of communities of color. She pointed to structural reforms needed to run a serious challenger campaign in California, in particular investing earlier in local field operations too often neglected in favor of advertising. Right now, she said, “you’re asking people to put their careers on the line for something that we might not have the infrastructure to support them to be successful.”

McBride agreed. “Anyone who put their hat in the ring would be doing it on their own and depending on their own networks. It becomes such a heavy cross and that has become the challenge for us.”

“If you want to defeat an incumbent sheriff in 2022,” Boucher said, “the work needs to start now.”

Looking ahead

Dujuan Armstrong was sentenced to serve nine weekends at Santa Rita. He did not survive the third and advocates want to know why.

His death has become a rallying point for the Ella Baker Center’s campaign to audit Ahern, encapsulating what activists see as the disregard for human life and lack of transparency that have defined Ahern’s tenure as sheriff and the board of supervisors’ reluctance to take action.

Rev. Davis-Howard, of Oakland Rising Action, says advocates will continue working to make Alameda County part of a growing national trend to elect more progressive sheriffs, or at least break the county tradition of uncontested races. “We are going to be intentional in the next four years to identify someone who is interested in running against him,” she said. “In Alameda County, people think once they’re elected it’s a lifetime appointment.”

For Bernal, the Ella Baker Center organizer, change is overdue. “There’s a long history in this country of the local sheriff who suppresses civil rights, from Bull Connor to Joe Arpaio to Sheriff Ahern. And if we can’t hold the sheriff accountable here, in Oakland, in progressive Alameda County…” His voice trailed off, exasperated.

Kyle C. Barry is senior legal counsel for The Justice Collaborative.