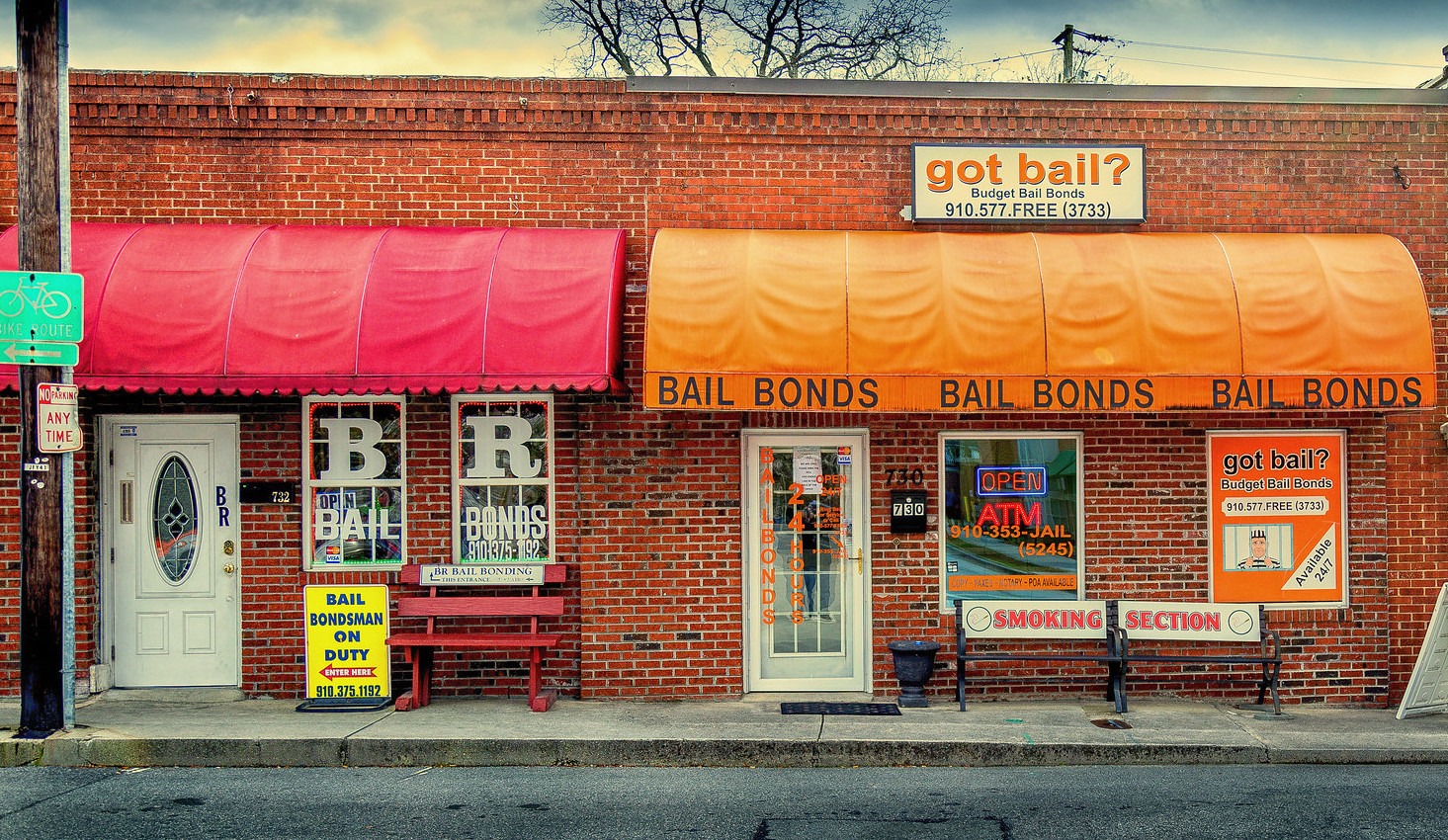

I Worked As a Bail Bond Agent. Here’s What I Learned.

Low-income women are fueling bail industry profits—and getting harmed in the process.

Toward the end of a long, boring shift, a young Laotian woman named Anna flew into the bail office. Her ex was in jail, and she had to bail him out. I explained that she needed to pay $150 (10 percent of the $1,500 bail) and co-sign the bond. As she read the co-signer agreement, she sighed and shook her head. She had recently left the defendant because she was tired of taking care of him. Here she was, taking responsibility for him again.

“So, why do it?” I asked. Anna felt she had no choice: If she didn’t bail out her ex, he would remain in jail, unable to work or help care for their child. Anna hurried through the paperwork and paid the cash, eager to get back to her mother, who was facing deportation to Laos.

I worked as a bail bond agent in a large urban county for a year and a half to study firsthand the operations of big-city bail and its effects on defendants and their families. Anna was just one of an enormous group of women positioned at the bottom of a system that generates huge profits for a relatively small number of players—primarily large insurance companies.

Before working bail, I assumed people paid their own bail. I was wrong.

These underwriters, or sureties, are insurance corporations with which most states require bail companies to partner. There are about 35 major industry players; with their backing, bail companies can write bonds far above their cash on hand. In exchange, the insurance corporations typically take 10 percent of each bond premium. In 2012, sureties secured more than $13.5 billion in bonds. These corporations risk little: In auto and property cases, insurance companies typically pay out 40 to 60 percent of their revenue in annual losses. Bail underwriters, records suggest, pay less than 1 percent in losses.

Women of color anchor the bail industry

Due to patterns of crime, policing, and prosecution, defendants in the U.S. are disproportionately poor men of color. (In 2016, 85 percent of people in jail were male and 52 percent were non-white.) Before working bail, I assumed people paid their own bail. I was wrong, and the reason was pretty simple: Most criminal defendants are poor; around 80 percent qualify for publicly provided legal counsel. Locked up and lacking resources, most people need someone on the outside to pay the bondsman. Their desperate plight offers the bail industry a way to tap their social networks for profit.

Defendants’ female relations (mothers, grandmothers, aunts, wives, and friends) typically come up with the funds to get them out of jail. Often, these women—disproportionately women of color—also agree to co-sign the bond (a requirement of many bail companies and sureties). Although anyone is allowed to pay the premium, co-signers must meet eligibility requirements. For example, the company I worked for required a co-signer to be at least 21 and have a decent-paying job.

By paying premiums and co-signing bonds, women like Anna provide the foundation of industry profits. At some point or another, I mentioned this observation to nearly all of my co-workers and agents at other companies. Without exception, they found my insight unremarkable; it was just “common sense.” And yet the burden on these women has far-reaching consequences, on both their financial security and well-being.

A debt of care

As Victoria Piehowski, Joe Soss, and I argue in a recent article, bail agents and their employers assume that women will take on the burden of bail. Women are expected to care for the young, sick, old, and, yes, the incarcerated, so bail agents and their bosses know they can be counted on to pay the premiums and sign the contracts.

These assumptions lead agents to actively target defendants’ female relations. Our managers regularly instructed us to ask defendants questions like “What’s mom’s name and number?” Mothers, they assumed, would care enough to bail out their children and make sure they showed up for court. Grandmothers and long-term romantic partners ranked second-best. “Girlfriends” were riskier: Supervisors told us to learn what we could about the relationship’s length and stability as a gauge for the girlfriend’s commitment to the defendant. Men co-signed sometimes, yet agents rarely mentioned men when discussing “best options.”

Women are expected to care for the young, sick, old, and, yes, the incarcerated.

When friends and family were reluctant to bail out someone, agents used care-based strategies to lock in a co-signer. By describing jail conditions as dangerous and unhealthy, for instance, agents evoked fear and guilt in potential co-signers. They emphasized negative legal outcomes tied to a person remaining in jail. Even people who aren’t guilty, for example, are more likely to take a plea bargain if detained and might “look guilty” appearing in court in an orange jumpsuit rather than their own clothes. Freed from lockup, defendants can strategize with attorneys, contact witnesses, and aid their case in other ways.

The bottom line agents conveyed was: If you really care—if you really want to take care of defendants in this awful situation—you will pay the premium and co-sign the bond.

Expanding inequality

There is a growing recognition that cash bail intensifies inequality based on race and class. Unable to afford cash bail or round up a co-signer, poor people often languish in jail with dire consequences, like job loss and even death. Alongside other criminal justice-related expenses like court fines and fees, bail payments drain wealth from low-income communities of color, further entrenching disadvantage.

There is less appreciation of how cash bail harms low-income women and reproduces inequality based on gender (in combination with race and class). Of course, poor female defendants experience a range of negative consequences. But another vast population of women, largely invisible in public discussions of bail reform, is brought into the system through the co-signing process. Handing over hundreds or thousands of dollars, these women may drain their savings or go into debt. Co-signing produces untold stress as the person considers whether to pay for bail or their bills. The process sometimes strains relationships—for example, when a co-signer’s romantic partner does not want them to use scarce resources to bail out a loved one. On several occasions, a co-signer emphasized the need to keep their action discreet and refused to list their partner’s contact information on the contract.

Co-signing produces untold stress as the person considers whether to pay for bail or their bills.

Co-signing is more than putting up money. Contract terms can give bail companies or their representatives (bounty hunters) permission to search co-signers’ homes, track their vehicles, and gain access to their private information, including medical records. Signatories are subjected to repeated phone calls, text messages, and emails. The process puts the co-signer in a similar position as the defendant, enduring surveillance and harassment sometimes long after the legal case concludes.

As an act of caregiving, co-signing can strengthen ties between the co-signer and defendant. But, as seen with Anna, those ties may be unwanted. Still, many co-signers may feel they have no choice, even when they personally suffer from a defendant’s alleged criminal behavior. For example, I worked with a Native woman named Angie whose partner, Johnny, had cheated on her with a minor. Angie was furious and hurt, but felt she had to bail out Johnny “for the kids.” Giving up $750 and signing the bail contract, Angie anxiously took responsibility for Johnny making his court dates. If he didn’t, she would face additional costs.

Cash bail systems draw poor women of color not only into extractive relations with bail companies and complex legal entanglements, but also, in many cases, undesirable social relations with the defendants. As policymakers and the public undertake difficult conversations about bail reform—including many county and state initiatives to end cash bail—we cannot forget the extreme costs of care that the bail industry and criminal legal system impose on already disadvantaged women.

Joshua Page is an associate professor of sociology and law at the University of Minnesota, and he is the author of “The Toughest Beat: Politics, Punishment, and the Prison Officers’ Union in California.” Victoria Piehowski, a University of Minnesota graduate student in sociology, and Joe Soss, the university’s Cowles Chair for the Study of Public Service, contributed to this commentary.