Commentary

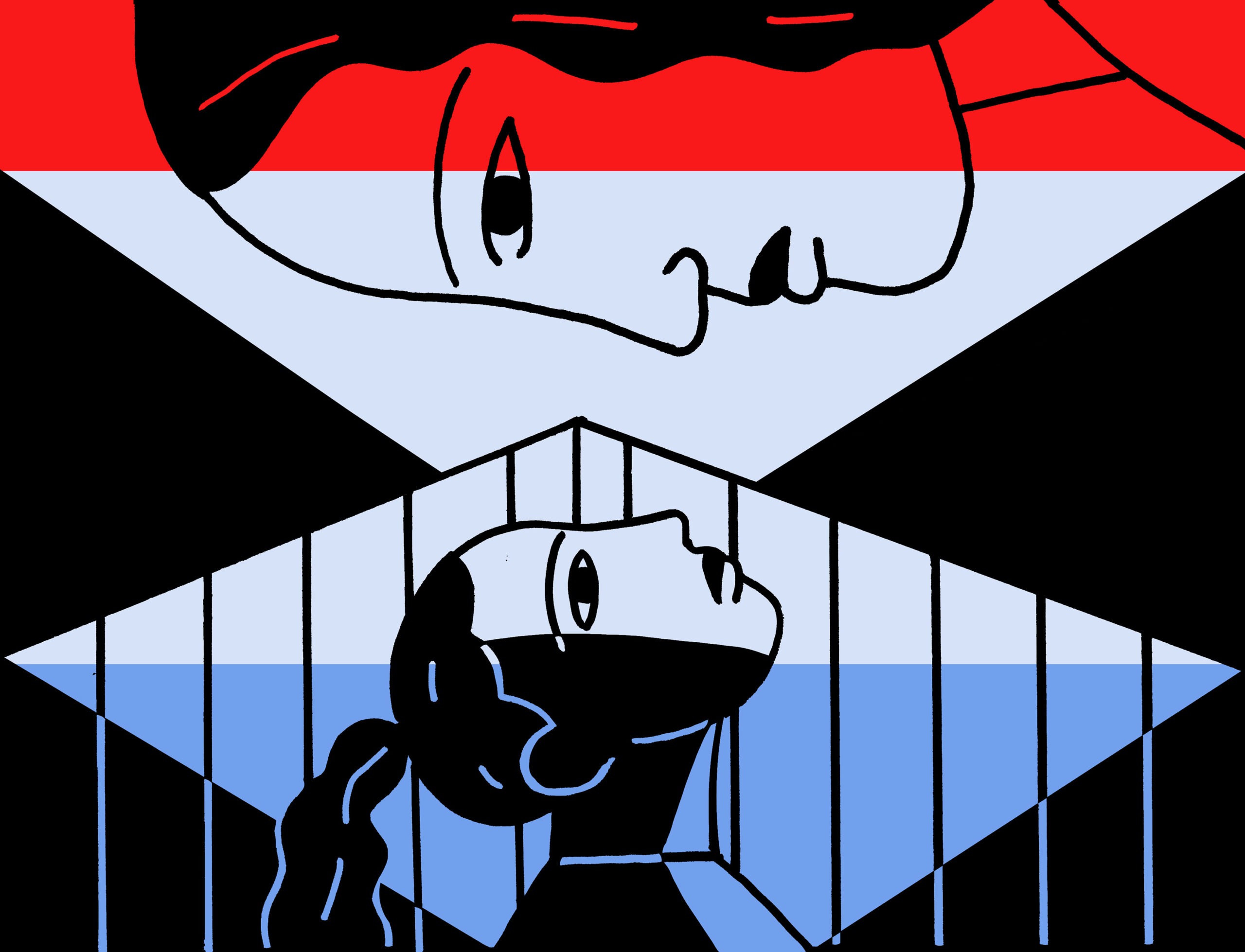

I Was A Child In An Adult Prison System. Now I Fight For Those, Like Me, Who Deserve A Brighter Future When They’re Released

As a staff member of the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, I fight for all children, especially those impacted by systemic racism in our criminal justice system.

“Left Behind,” a collaboration between The Appeal and Oregon Justice Resource Center, presents firsthand accounts of growing up in prison from individuals sentenced as children to 25 years-to-life. Inspired by the Supreme Court’s ruling in Miller v. Alabama, which prohibits the imposition of a mandatory sentence of death in prison for children, this series reveals the humanity of those given life sentences by asking: What obligations do we have as a community of not leaving them behind?

I’ve had a long time to think about what I did when I was 13. That was how old I was when I ceased to be a daughter, sister, niece, student, and friend and became instead a murderer, super predator, killer, felon, criminal, and inmate. What little innocence I had I exchanged for an inmate identification number. I was a 13-year-old charged with second-degree murder.

I don’t tell the story of how this came about to excuse what I did. I know nothing can undo the past. I can’t bring back the life I took or ease the pain. I was a broken, abused child using a child’s logic in making a decision with very adult consequences. I want people to understand that I was still a child, despite what I did, and so are the others like me. People are horrified at the thought of leaving a dog in a hot car, but readily allow children to be sentenced to death by incarceration. Until we can all understand that young people who commit these types of crimes are still human, we will not be able to heal the harm caused or offer everyone involved the chance of a better future.

I didn’t keep quiet. I tried to tell people around me what was happening to me, what my uncle was doing to me, but they wouldn’t listen. I told my father, my school counselors, Department of Human Services workers, and even a local preacher about how my uncle was sexually abusing me, but they did nothing. The abuse began when I was about 5 years old and continued right up until I was arrested. I don’t know when I decided the solution was to kill my family, but it seemed to me at the time like it was my only option. But, having murdered my stepmother, I didn’t end up going through with the others. My younger brother and co-defendant saved them.

I don’t have space to tell you every story of the more than 16 years I spent inside the adult prison system. How, for over 10 years, I became a product of my environment: hard, callous, mean. It wasn’t until I met my mentors, Ma Betty and Papa Charles, who saw through my tough exterior and saw my potential, that I realized there was more to life—more to my life—than what was inside the barbed wire. Love, empathy, and compassion changed my life and the lives of everyone around me. I will say that I live every day in repentance. I try to save others every day in the hope it will somehow absolve me of the life I took.

From the moment I was incarcerated, I was working toward my release. In my imagination, when I walked out of those gates, I would be walking into a new beginning. I would have a blank slate and could become anyone I wanted to be. Every possibility would be open to me. It wasn’t easy to keep moving forward while I was in prison. Priority for programs and services inside is given to people who are being released soonest. In the view of the Department of Corrections, it’s a waste to educate someone who won’t be free anytime soon to use the skills they’ve gained. I had to fight for the certifications and training I’ve gotten. When I couldn’t get what I needed from the prison I was in, I took correspondence courses by mail and earned my degree in religious education. I pored over all the information I could find about re-entry and how to successfully transition back into the community. So much so, I even ended up teaching other women in the re-entry class during the last six months I was there. I was ready.

The day I had been waiting for finally arrived on Aug. 1, 2015. I had been dreaming of that moment for more than half my life. At last it was time for me to put the past behind me and begin fresh. I felt full of hope and excitement about what was ahead as I walked out of the prison gates. On my list: reuniting with my family, going to college to get a degree, finding a good job, getting married, and having a family. I felt ready for anything. Hadn’t I spent years making sure I would be prepared for every part of my life after prison? I even took marriage and parenting classes during my stay, despite not being married or a parent. That’s how certain I was that if I only took the trouble to read one more book, take one more class, I could be ready for anything.

It didn’t take a week for reality to come crashing down. Within days, I saw that the fantasy of life after prison that I had built in my mind wasn’t real. My family who had learned to survive without me for most of my life, couldn’t seem to figure out where I fit in. They had missed my growing up years. I had missed most of their lives. I was essentially a stranger, living in a strange house, confused and unsure where I belonged.

The biggest reality check came when I checked learning to drive off my list and set out to find a job. With all the preparation I had done, my interview skills were top-notch. I left most places with a job offer. I was upfront about my past and, while it dimmed the light in their eyes a little, most employers told me they were willing to look past it, if the higher-ups said it was OK. By the third or fourth time, I realized that meant I would never get a call back. I can’t tell you how many times I left an interview and sat in my car for an hour crying in disappointment.

It wasn’t all bad. A highlight was receiving a presidential academic scholarship at the local community college. Another highlight was relationships with people who care about me. My brother, my mentors, and the family I’ve made through ICAN, the Incarcerated Children Advocacy Network, helped me remain grounded and reminded me that I am not defined by my past mistakes. That truth isn’t easy to hold on to when society keeps labeling me a felon and a murderer. With every rejected rental application and failed job interview, I was falling deeper into despair. But I kept going. My worst day out here is better than my best day in prison. Prison time breeds resilience. You learn to take the punches and keep going.

Joining ICAN has been a saving grace for me. This group is made up entirely of people formerly incarcerated as children who had lengthy and even lifetime sentences but are now free due to changes in the law or advocacy efforts. A place for me to belong, surrounded by people just like me, who understand exactly what I’ve been through as a child in prison, and what it’s like to come home almost two decades later to an unfamiliar world. My fellow ICAN members understand my pain, confusion, and struggles and are on the same journey of restoration and redemption. Until I joined this community, I didn’t know the value of a support system. I thought I could do it alone. I now know that a support system is vital.

Four years after joining ICAN, I became a full-time staff member of ICAN’s parent organization, the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth. Now, I had a job I could be proud of that allowed me to pursue my purpose: fighting for those I left behind and creating a brighter future for all children, especially those marginalized and impacted by systemic racism in our criminal justice system. This was a way for me to channel all the emotions I had when I was cast out by the community, my chance to make a difference.

The fantasy I had about freedom may not have come true, but I have realized over the years that it doesn’t need to. I am making a new life for myself that’s better than anything I could have imagined while I was in prison. It’s not all sunny skies and rainbows, but it’s mine, and I’m free to make it whatever I want.

Catherine Jones was in Florida State Prison until her release in 2015. This column was edited by Alice Lundell, director of communication for the Oregon Justice Resource Center.