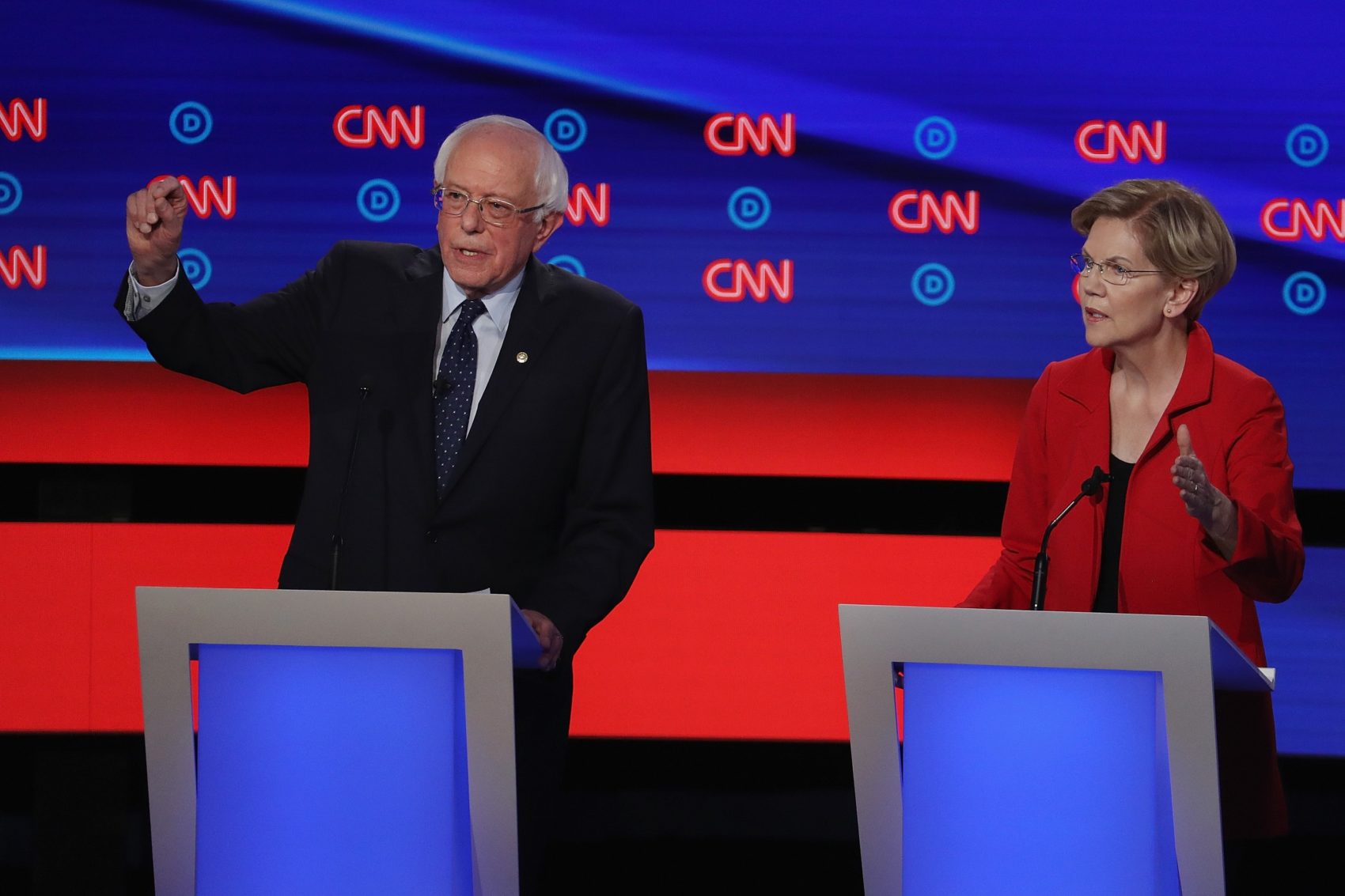

How Warren And Sanders Would Overhaul The Criminal System

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. This week, the two most progressive frontrunners for the Democratic presidential nomination, Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, added their criminal justice proposals to the pile. They […]

|

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. This week, the two most progressive frontrunners for the Democratic presidential nomination, Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, added their criminal justice proposals to the pile. They presented the world with two similar pictures of a far more enlightened system, one that takes no pleasure in the suffering of others and respects the dignity of each person involved. The plans generally cover the same ground, both of them opposed to the death penalty, cash bail, solitary confinement, private prisons, and the school-to-prison pipeline. Both would legalize marijuana and safe injection sites, provide support for survivors of crime, and invest in re-entry services, mental health treatment, officer training, and public defenders. Sanders and Warren both emphasize the racial disparities and discrimination that underlie the current system. Both candidates, crucially, call for expanded data collection on police use of deadly force. Either of these plans, if implemented, would be a tremendous and welcome change. The difference between the two seems dispositional. Warren begins her plan with a panorama shot, suggesting that we “reimagin[e] how we talk and think about public safety,” because “it is a false choice to suggest a tradeoff between safety and mass incarceration.” Public safety, she says, “should mean providing every opportunity for all our kids to get a good education and stay in school,” “safe, affordable housing,” “violence intervention programs,” “policies that recognize the humanity of trans people and other LGBTQ+ Americans and keep them safe from violence,” and “accessible mental health services and treatment for addiction.” Warren would invest less in incarceration and more in “services that lift people up” to “decarcerate and make our communities safer.” It’s not that Sanders wouldn’t support such policies—in fact his plan has strong proposals on each of them (except on the protection of LGBTQ people, which he does not mention). But Sanders begins in his comfort zone, with a section calling for an end to “the practice of corporations profiting off the suffering of incarcerated people and their families.” Warren addresses this need, too, but not until she has thoughtfully urged a rethinking of public safety, a change in what “we choose to criminalize,” reforms in “how the law is enforced,” and a “restructuring of incarceration and re-entry.” Warren’s approach makes clear that her thinking and approach are methodical. Warren also works harder to explain how she would accomplish each proposal. Warren and Sanders both support various policies over which a president has, at best, indirect influence, such as bringing down the state prison population and eliminating collateral consequences. Warren, however, takes more opportunities to identify the specific mechanisms she would use to effect these changes, and tends to be more upfront about the reforms that will simply be difficult. “The federal government oversees just 12% of the incarcerated population and only a small percentage of law enforcement and the overall criminal legal system. To achieve real criminal justice reform on a national scale, we must move the decisions of states and local governments as well,” Warren writes toward the end of her proposal. “Federal grants make up nearly one third of state budgets, and states and local authorities spend about 6% of their budget on law enforcement functions. My administration would reprioritize state and local grant making toward a restorative approach to justice, and expand grant funding through categorical grants that require funds to be used for criminal justice reform and project grants that require funding to be allocated to specific programs. When necessary, my plan would also use federal enforcement authority.” Warren also keys into one of the most important issues over which presidents do have some control: appointing federal judges. Warren promises to “appoint a diverse slate of judges, including those who have a background defending civil liberties or as public defenders.” Federal judges matter because they effectively set the rules for policing. They often decide whether police or corrections officers used excessive force or otherwise violated a person’s rights, and they decide the legality of tactics such as stop-and-frisk. They are also the key to accountability when officers break the rules, deciding whether officers are entitled to immunity in civil suits, and monitoring compliance with consent decrees when departments must implement systemic reforms. They rule on habeas petitions, filed by people who believe they are wrongfully imprisoned. Warren’s promise to appoint public defenders, in addition to her opposition to the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, could breathe new life into habeas. Sanders ignores the issue of judicial appointments entirely. But in many ways, the world presented by Sanders might be preferable. Unlike Warren, Sanders would “limit ‘absolute immunity’ for prosecutors,” which shields prosecutors and their offices from liability, even when they are found to have committed wild acts of misconduct. Warren does not mention absolute immunity, although she does support open-file discovery and forming a commission on prosecutorial conduct. Both Sanders and Warren would “limit” qualified immunity, the permissive standard that often allows police to hurt or kill civilians without consequence. Neither candidate made clear how they would limit this standard. Sanders would, importantly, establish a “federal no-call policy, including a registry of disreputable federal law enforcement officers, so testimony from untrustworthy sources does not lead to criminal convictions.” He would also “provide financial support to pilot local and state level no-call lists.” Under Sanders, federal parole would be reinstated and people serving long sentences would “undergo a ‘second look’ process to make sure their sentence is still appropriate.” Both candidates support responsible use of police-worn body cameras, but only Sanders would establish third-party agencies to oversee the storage and release of police videos, an issue close to this writer’s heart. Sanders also says he would “ban the prosecution of children under the age of 18 in adult courts,” and, if he intends for this to be implemented without qualification, it would include younger people tried as adults based on the severity of the charge, a policy shift that would be radical, necessary, and completely sensible. But the path toward such a shift in every state is not made clear. On more general issues of poverty and inequality, which are crucial to any comprehensive criminal justice plan, Sanders is on firmer ground. He would use federal funds to expand a “sustainable community school model which will fund trauma-informed care and services in schools,” end payday lending, tie transportation funding to improvements in transit in urban centers, provide grants to entrepreneurs of color, and pass the WATER Act “to create a $35 billion annual fund to remove and replace lead pipes in communities throughout the country.” Although both candidates express concern about prison and jail conditions, neither mentions the Prison Litigation Reform Act, a 1996 law that was passed during a wave of incarceration, when prisoners were bringing lawsuits claiming that their constitutional rights were being violated. Instead of addressing prison conditions, Congress decided to severely limit the amount and type of relief that federal judges can grant, and prisoners can receive. Repealing the PLRA should be a natural suggestion for any presidential candidate that cares about the way we treat prisoners in this country. Both of these plans are impressive, and reflect a tremendous effort to understand the causes of our mass incarceration crisis and the solutions. They are also both massively ambitious and, even if Warren or Sanders takes the White House, and even if Democrats control one or both legislative bodies, many of the proposals would still be long shots. But it is meaningful to see the points together, forming a coherent vision encompassing housing, education, healthcare, labor, and discrimination, along with more traditional criminal justice issues. It seems that both candidates understand that the problems undergirding our criminal system are systemic and widespread. “We must move away from an overly-punitive approach to public safety and start focusing on how to safeguard our communities, prevent the conditions that lead to arrests, and rehabilitate people who have made mistakes,” writes Sanders. According to Warren, “We cannot achieve this by nibbling around the edges—we need to tackle the problem at its roots. That means implementing a set of bold, structural changes at all levels of government.” These statements alone from two frontrunners for the Democratic nomination are remarkable. The Sanders plan is slightly more aspirational; Warren’s is somewhat more practical. But what else did we expect? |