How COVID-19 Is Affecting Assault Survivors Seeking Care

In New York, fewer people who have experienced sexual assault or rape have sought forensic exams at hospitals during the pandemic. But advocates suggest that’s not evidence of declining sexual violence.

In the 22 years she conducted forensic exams before retiring in the spring, Karen, a nurse in the New York City area, treated thousands of sexual assault victims. There was always an ebb and flow to her caseload. At her last place of work—which she asked The Appeal to withhold, as well as her last name, since she didn’t have permission to speak with the media—anywhere between 15 and 40 people would come in each month requesting an exam.

Only twice in her career was this ebb and flow interrupted, she said. The first time was 9/11: After the Twin Towers fell, Karen said she went six weeks without seeing a case. Yet nothing has compared to the changes wrought by the coronavirus crisis, she said. Between March 1 and March 19, 18 individuals entered Karen’s hospital requesting a forensic exam. Between March 20 and May 1, her last day of work, the number dropped to four.

Yet Karen knows the drop in people requesting exams doesn’t necessarily mean there’s been a drop in sexual violence. In fact, most experts believe that sexual assaults, like all other forms of interpersonal violence, will and have only become more frequent as the pandemic continues.

In New York City and across the country, medical practitioners and advocates are concerned that too few survivors have sought care amid the COVID-19 crisis, and suggested that emergency preparedness measures could have helped address the problem from the start. And as the economic fallout from the crisis continues and some states and cities begin to open up, the numbers of individuals vulnerable to sexual violence may only grow larger, they fear.

In the U.S., 85 percent of forensic nursing programs operate out of emergency departments, according to the International Association of Forensic Nurses (IAFN), and in recent months, emergency departments across the country have had a sharp decrease in the number of individuals seeking care for non-COVID-19 related medical issues. In a survey conducted in the spring by IAFN and released to The Appeal, four out of five programs reported seeing a change in the volume of patients coming in for care. Of those who reported seeing a change, 94 percent said they experienced a noticeable decrease in patient volume.

Although the placement of forensic nursing in emergency departments may have streamlined access to services in the past, right now the opposite is most likely true: Recent survivors, like others with medical needs, are fearful they could become sick simply by going to the emergency department.

Amy Smith is a New York City nurse practitioner and forensic examiner and also helps train nurses to conduct the exam. “Part of me is like, phew! Because it’s a very long exam and now you’re keeping somebody in a contaminated situation for a long period of time,” she says. “But the other part of me knows in my heart that it’s only a relative decrease, not an actual decrease. So that means [survivors are] not getting help.”

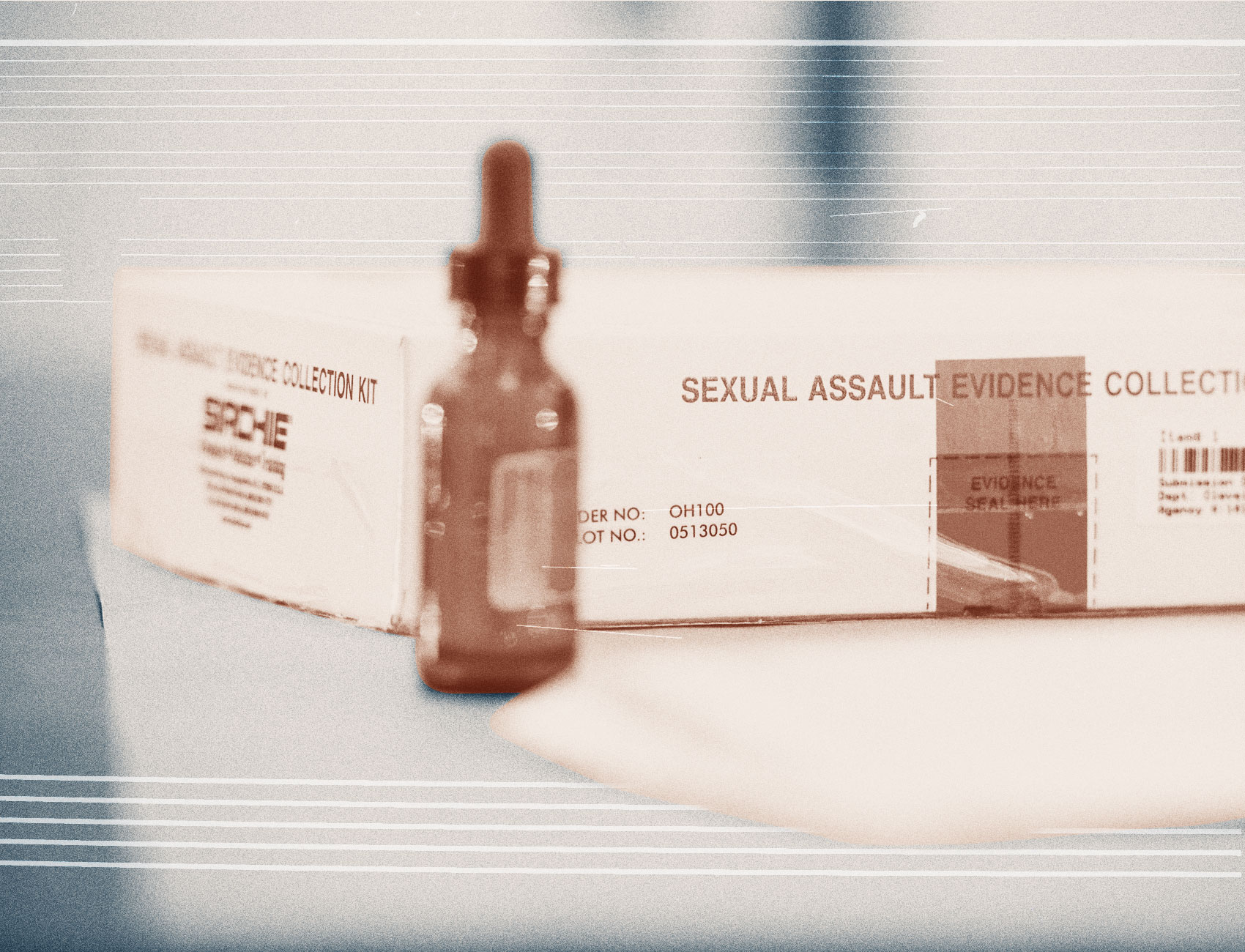

Yet not visiting the emergency department for a forensic exam has a cost: Survivors could lose the opportunity to gather physical evidence of the assault or rape. There’s a very small window to collect this evidence; usually exams aren’t performed more than 72 hours after an assault. If someone is uncertain about pressing charges, they can generally choose to undergo the exam and ask the hospital to hold their kit before turning it over to the police. Once the three-day window closes, however, any forensic evidence left on the victim’s body is lost forever.

In New York State, the Office of Victim Services (OVS) covers the cost of forensic rape exams for anyone who doesn’t have access to private health insurance or opts not to use their private insurance for the exam. That includes paying for any pharmaceuticals given or prescribed over the course of the exam. Individuals who have other injuries related to the crime, such as a broken arm, can also file a claim to have the expenses covered by OVS.

But hospitals and medical providers have filed far fewer forensic rape exam reimbursement requests with OVS since the pandemic began, compared to previous years. Indeed, OVS received 273 requests in March and 143 in April, compared to 547 and 502 requests during the same months of 2019, according to data provided to The Appeal by OVS.

However, these numbers should not be used to draw any definitive conclusions about survivors’ willingness to seek medical assistance since the pandemic began, said Janine Kava, the OVS director of public information. For one, some individuals use their own insurance to cover the cost of the exam, and not all providers ask the state for reimbursement. In addition, many providers “bundle” their OVS claims as a means of streamlining the process—meaning a host of requests are sent all at once, rather than as they occur. Given the immense pressure placed on hospital administrations since the pandemic began, it’s possible facilities have been especially slow to file claims with OVS during this time.

The issue isn’t merely whether fewer people are coming in for forensic exams, but how the exam experience is changing for people who do go to the emergency department. Normally, a person who goes to aNew York City emergency department and reports experiencing sexual or physical violence is paired with a social worker or extensively trained volunteer advocate, who provides trauma-informed emotional support and stays in the room while the patient undergoes the exam, if that’s requested.

For months, volunteer advocates were barred from physically entering many emergency departments. Although the staff is offering to connect patients to advocates by phone, it’s an option few survivors are using, said Camille Cooper, the vice president of public policy at the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN). “The loss of that support is incredibly significant,” she said.

In New York and other areas hit hard by the virus, the task of conducting exams stressed an already overburdened hospital system. Forensic exams can take four hours or longer to complete, and providers are sometimes interrupted or under pressure to finish as quickly as possible.

As Smith, the nurse practitioner, explained it, the exams have always strained resource-starved and understaffed facilities. The coronavirus has simply exacerbated those difficulties. “All of the things that were maybe a little bit of a concern are now completely elevated—just like everything else.”

These stressors are significantly affecting patient care. In April, Sara Zaidi, the assistant director of intervention at the New York City Alliance Against Sexual Assault, told The Appeal she had heard stories of survivors being turned away from emergency departments, even though hospitals are required to conduct the exams upon request. By late May, she said things had improved at the city’s hospitals—there’s more personal protective equipment, or PPE, for providers and more clarity on the process for survivors seeking exams. She also said there have been locations set up off-site from emergency rooms, including in obstetrician and gynecologist offices, where survivors can undergo exams.

Even though the numbers of people going to hospitals to undergo forensic exams has decreased across the country, the number of children and adults actually experiencing sexual violence at the hands of family members or friends has most likely grown considerably. In March, for the first time ever, minors constituted half of the victims who called RAINN, according to data released by the organization. Of the minors who called the organization’s hotline and discussed COVID-19-related concerns, 67 percent said their perpetrator was a family member and 79 percent said they were living with the person causing them harm. News reports from the United Kingdom, mainland Europe, and Latin America also indicate that the virus has led to a considerable increase in the frequency and severity of intimate partner violence.

Past research, including a study that tracked rates of violence in West Africa after the Ebola epidemic, have suggested that even pandemics do not reduce the chances of stranger-based sexual assaults. In an interview with The Appeal, Alina Potts, a research scientist with the Global Women’s Institute at the George Washington University, explained that the Ebola epidemic produced new relationships of dependency between the population at large and those able to provide critical care, some of which were exploitative. For example, Potts explained, a vaccinator told someone she would only receive an innoculation in exchange for sex. Children whose parents or extended family died needed to find a way to eat, and that sudden vulnerability placed them at great risk of sexual exploitation.

There’s already evidence that the social and economic upheaval brought about by the pandemic is placing women, children, and other vulnerable populations, including trans and gender nonconforming people, at greater risk of violence. In May, BuzzFeed News reported that some landlords have been demanding sex from tenants unable to pay rent. In June, the BBC reported that COVID-19 was placing street sex workers at a heightened risk of sexual assault.

Perpetrators of assault are “opportunistic,” said Cooper of RAINN. “When people are vulnerable, when they have food security issues, when they have job security issues, when they have housing security issues, when you see large numbers of people in these temporary medical facilities—there are going to be opportunities for people to offend in those contexts too.”

Experts told The Appeal, previous natural disasters have shown that the heightened risk of violence can be mitigated with the appropriate planning and foresight. Laura Palumbo is the communications director at the National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC). In a survey conducted by the center of 47, self-identified survivors assaulted during or immediately following Hurricanes Rita and Katrina, almost a third of respondents said the violent incident had occurred at an evacuation site or other shelter.

For Palumbo, the data laid bare the blind spots of planners in attempting to create safe emergency housing. “We can help mitigate that risk of domestic and sexual violence during natural disasters and be building our response systems to natural disasters with this information in mind,” she said. The NSVRC has since published a guide about how to prevent and respond to sexual violence after a disaster, which includes many practical and tangible recommendations like ensuring adequate lighting will remain in shelters even if the electricity goes out.

To some degree, the current inability of emergency departments to meet the needs of survivors indicates the necessity of considering other long-term options. The Philadelphia Sexual Assault Response Center is a physical space solely dedicated to providing forensic services to survivors: Individuals only need to call the center’s emergency hotline and a trained nurse will meet them shortly thereafter at the office space. The one-to-one care means that a provider’s attention can be undivided during an exam, explains director Barbara Osborne, and the different model also means the center’s services have been affected very little in recent weeks.

Still, Osborne emphasizes that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to providing forensic care. “I always want survivors to know that regardless of the outlet for care, we’re still here, we’re still providing services,” she said. “Even in the midst of a pandemic, we want survivors to seek the care they need.”