How a Tool to Help Judges May Be Leading Them Astray

In Cook County, Illinois, 99 percent of defendants deemed ‘high risk’ for pretrial violence don’t reoffend.

On any given day in Chicago, roughly 90 people charged with felonies file into the hearing room of Cook County’s Central Bond Court. One by one, each stands before the judge overseeing court that day, who confirms their name and reads out the charges against them.

Then, the judge is given a crucial piece of information: a computer-generated recommendation regarding whether to release the defendant and with what level of supervision. Each recommendation is based on the person’s scores on the Public Safety Assessment (PSA), a tool designed to measure someone’s risk of missing future court hearings or committing a new crime if released. The PSA also attempts to predict which people are at an especially high risk of committing violent crimes if released.

After brief statements from the prosecutor and defense attorney, the judge decides whether to release the defendant, and under what conditions. The whole process often takes less than a minute.

PSA scores are one of many factors judges use in deciding someone’s fate, but they carry significant weight: Nearly three-quarters of defendants categorized as low risk will be released immediately after their hearings, sometimes with an order to check in regularly with pretrial services officers. But nearly all considered high risk will be sent to Cook County Jail, where they will either have to make bail, which averages about $6,000, or sit in jail for weeks, months, or even years while they wait for their cases to finish. About a third of “high risk” defendants will be denied any chance at bail.

Cook County began using the PSA four years ago in response to concerns that it kept too many people in jail before trial. The PSA, launched in 2012 by Arnold Ventures, a nonprofit that funds evidence-based policy interventions, promised to take some of the guesswork out of pretrial release decisions, giving judges overseeing bond hearings a supposedly objective measure to lean on and reducing the chance of bias.

But new data released by the Cook County Circuit Court in May and analyzed by The Appeal suggests the PSA may be overstating the risk defendants actually pose if released. Between October 2017 and December 2018, 99 percent of people flagged as high risk for violence who were released before trial were not charged with any new violent crimes during the release, a percentage virtually identical to the one for those deemed low to moderate risk.

“Half of 1 percent of people without a risk of new violent offense were rearrested, and 1 percent of people with the violence flag were rearrested,” said Sharlyn Grace, executive director of the Chicago Community Bond Fund. “That’s not a very effective prediction.”

Experts on risk assessment share her concerns. “A vast majority of even the highest-risk individuals will not commit a violent crime while awaiting trial,” several wrote in a recent New York Times op-ed. “If these tools were calibrated to be as accurate as possible, then they would simply predict that every person is unlikely to commit a violent crime while on pretrial release.”

Risk assessment and bail reform in Cook County

When it adopted the PSA in 2015, Cook County was home to the largest jail in the country, and 90 percent of the people there were detained pretrial, so they had not been convicted of any crime. Local officials promoted the PSA as a “scientifically validated” approach to pretrial detention, allowing them to distinguish people who could be safely released from those who posed a true threat to public safety.

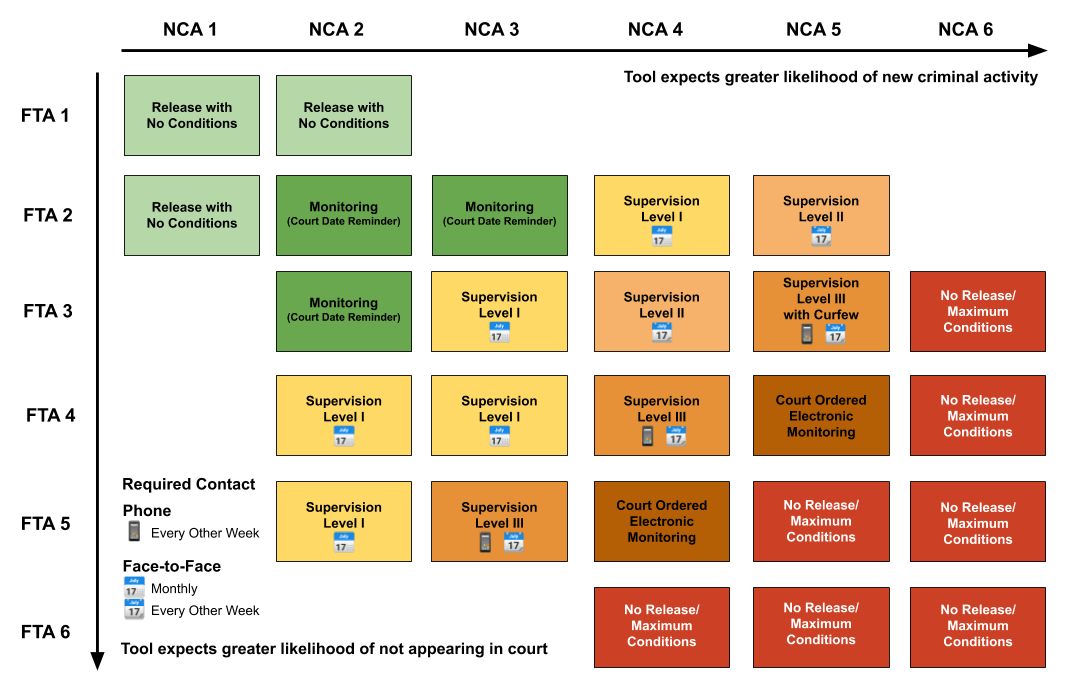

In Cook County, people with the lowest risk scores are recommended for release with no conditions attached, while people with the highest risk score are recommended for pretrial detention. Those in the middle are recommended for release with varying levels of supervision by Cook County’s pretrial services division.

The program saw fast results. In the two months after the PSA’s full implementation, 67 percent of defendants in nonviolent, non-weapons cases were released without having to pay a money bond, compared with 52 percent three months earlier. But overall detention rates remained stubbornly high; the increase in release rates for defendants considered low risk was offset by high detention rates for those labeled high risk.

In 2017, the circuit court went one step further when Chief Judge Timothy C. Evans issued an order requiring judges to impose “the least restrictive conditions” needed to ensure defendants appeared in court proceedings and did not pose a threat to anyone’s physical safety. The order also required judges to avoid money bail whenever possible.

Though critics have noted that many judges still set onerous bail amounts, Cook County jail populations have fallen by nearly 20 percent since the order went into effect in September 2017. Release rates for those in the lowest risk category now exceed 97 percent.

But most “high risk” defendants are still detained pretrial. More than half are not released at any point before their cases are resolved, and most of those who are must pay at least $2,000 for bond or agree to electronic monitoring.

Criminal legal reform advocates say this disparate treatment is most likely because judges overestimate the threat “high risk” defendants pose.

“In many ways, I think risk assessments are lazy,” said Grace. “Part of the reason they’re popular is because it’s really hard and we’re uncomfortable with admitting that … we actually can’t predict and possibly shouldn’t even be trying to predict what will happen in the future.”

One potential problem with the PSA is that it was created with data from jurisdictions other than Cook County, producing standards that don’t reflect the actual risk the county’s defendants pose. In the data that Arnold Ventures used to create the PSA, 55 percent of people who received the highest risk score for new criminal activity were rearrested during their pretrial release, and 7 percent of people who received the highest risk score for violence were rearrested for a violent crime during their release.

But Cook County Circuit Court data shows much lower pretrial recidivism rates. Just 24 percent of people released between October 2017 and December 2018 who were given the highest risk scores for new criminal activity on the PSA were actually charged for new criminal offenses during their release, less than half the rate reported in the training materials. And fewer than 1 percent of defendants flagged as high risk for violence were charged with new violent crimes during their release, a rate more than 10 times lower than reported in the training documents.

Even though the vast majority of people released pretrial aren’t charged with any new offenses, critics of bail reform have blamed people released pretrial for violent crime. On July 18, Mayor Lori Lightfoot expressed concern that the PSA excludes gun possession from its definition of violent crime that pretrial services uses to calculate risk scores. Two weeks later, the Chicago Police Department released a public database listing the names of every person charged with gun possession released on bond since May 1.

According to circuit court data, however, fewer than 1 percent of people charged with weapons possession committed violent crimes during their pretrial release. Additionally, the Chicago police data shows that just 41 of the 1,095 people charged with a gun-related offense who have been released since May 1 have been rearrested for any crime.

Grace says confusion and inflated fears about the risk of releasing defendants are widespread among judges, attorneys, and local advocates. That may be why risk scores are rarely challenged, she said.

“I could probably count on one hand the number of times I’ve seen defense counsel contest the risk assessment scores when they’re high,” she said. “There’s absolutely not a literacy among defense counsel or advocates even about what the actual categories mean.”

In a statement, Cook County Circuit Court spokesperson Pat Milhizer told The Appeal that “all bond court judges, pretrial services staff, and stakeholders were trained on the use of the PSA tool” before it was introduced, and more training was offered before the chief judge’s order was carried out. Milhizer also said that judges receive quarterly reports updating them on new criminal activity rates for people they release before trial that includes the defendants’ PSA risk scores.

A ‘universal’ risk assessment tool

In 2012, when Arnold Ventures introduced its PSA, pretrial risk assessment tools were relatively uncommon. Fewer than 10 percent of jurisdictions used such tools for pretrial release, and many that were in use, such as the Virginia Pretrial Risk Assessment Instrument, were developed with historical data from just a handful of jurisdictions, meaning their predictions were often inaccurate outside the places where they were created.

Arnold Ventures created the PSA as a lower-cost alternative to existing tools, giving jurisdictions that wanted to adopt pretrial risk assessment a ready-made solution that could be implemented in eight months or less. In hopes of creating a “universal” risk assessment tool that could make accurate predictions in every jurisdiction, two prominent researchers hired by Arnold Ventures, Marie VanNostrand and Christopher Lowenkamp, analyzed nearly 750,000 cases from 300 jurisdictions to identify factors that could reliably predict defendants’ risk of missing future court appearances, committing new crimes, and committing violent crimes if released pretrial.

Since then, the PSA has expanded rapidly: According to Arnold Ventures, more than 40 jurisdictions, comprising more than 15 percent of the U.S. population, use the tool, including the entire states of New Jersey, Arizona, Utah, and Kentucky, as well as cities like San Francisco and Cleveland.

But many experts say that using a risk assessment tool that is calibrated with national data may lead to inaccurate predictions on the local level, as could be the case in Cook County. Criminal-legal practices differ widely across jurisdictions, as do demographics. In cities with racial disparities in arrest rates, for instance, those disparities can be mirrored in the risk assessment.

“One jurisdiction might have particularly heinous racial biases in arrest data, where another jurisdiction might be a 98 percent white jurisdiction,” explained Logan Koepke, a senior policy analyst at Upturn, a group that researches the impact of digital technology on civil rights and social equity. “These local differences matter a lot in terms of porting a risk assessment into a local context.”

Only a handful of jurisdictions that use the PSA have released data on the accuracy of its predictions, but so far, the results highlight the vast differences in localities. For instance, a 2018 study funded by Arnold Ventures that examined more than 160,000 defendants released pretrial in Kentucky between July 2013 and December 2014 found that only 3 percent of defendants flagged as high risk for violent crime were arrested for new violent offenses upon release, compared with 1 percent of defendants overall.

Despite these low rates of violence, training materials used by the Kentucky court system as recently as last month claimed that people flagged as high risk for violence were 17 times more likely to commit violence. When The Appeal asked about this discrepancy, a spokesperson for the court system said the figure was a mistake and would be corrected.

In contrast, New Jersey reported much higher rates of pretrial recidivism: According to the New Jersey Courts’ annual report for 2018, 14 percent of those in the highest risk category who were released were then rearrested for violent crimes. These discrepancies may be partly attributed to differing release rates between jurisdictions, according to Peter McAleer, communications director for the New Jersey Administrative Office of the Courts. New Jersey releases 96 percent of defendants pretrial, while Kentucky releases 69 percent, and Cook County releases 84 percent.

Additionally, using a national tool like the PSA makes it difficult for jurisdictions to recalibrate their risk assessment tools if local conditions change, creating the specter of what Koepke calls “zombie predictions,” or estimates of risk based on data that doesn’t reflect the effect of reforms. For instance, studies have found that text message reminders for court dates can reduce missed court dates by as much as 25 percent. If a jurisdiction that recently started text message notifications uses a risk assessment tool based on data from before the notifications began, the risk assessment will overestimate the possibility of missed court appearances.

In a statement, David Hebert, a spokesperson for Arnold Ventures, told The Appeal: “The PSA’s focus and functionality remain consistent, regardless of the geographical location of any particular jurisdiction,” and that “local factors and considerations” can be taken into account in deciding what release conditions to set for each risk level.

But Matthew DeMichele, the lead author of the Kentucky study, suggested that jurisdictions could improve the accuracy of their risk assessment tools by regularly recalibrating scores to reflect local conditions, though he noted that many jurisdictions don’t collect adequate data to evaluate their pretrial release programs.

“How many judges you think know their FTA [failure to appear] rate? How many pretrial officers, how many prosecutors?” he said. “I think the criticism of risk assessment is great, but it suggests that the field is further ahead than it is.”

How risky is too risky?

Beyond the issue of local validity, some critics of pretrial risk assessment tools question the logic of using “risk” to justify pretrial detention at all. Sandra Mayson, a professor at the University of Georgia School of Law, noted in a 2018 law review article that the U.S. Supreme Court hasn’t offered any clear guidance about what level of risk is necessary to justify such detentions.

Mayson proposes the “parity principle,” which she defines as the idea that courts should apply the same standard of danger for pretrial detention as it would for people not accused of crimes. If a 3 percent risk of violent crime wouldn’t justify detaining someone not facing criminal charges, then it shouldn’t justify pretrial detention either, Mayson argues.

“I think people discount the well-being and liberty of people accused of crime, because we see them as already guilty,” Mayson told The Appeal. “I think we’ve been willing to tolerate exorbitant rates of pretrial detention in part because of that.”

Nonetheless, Mayson doesn’t dismiss the usefulness of pretrial risk assessment altogether. She supports using assessments that clearly communicate statistical probabilities of pretrial failure as part of a broader adversarial release hearing, with ample defense for the accused.

“I think they can play a useful role first, in giving judges some political cover and second, in helping people understand just how limited the risk is for the vast majority of people,” Mayson said.

Hannah Sassaman, policy director for Philadelphia-based Media Mobilizing Project, hopes that Cook County will follow the lead of other jurisdictions that are rethinking how they use pretrial detention. In April, for instance, Dallas County District Attorney John Creuzot announced a new pretrial release policy that calls for a presumption of release with no conditions for people charged with misdemeanors and low-level felonies, while limiting the use of risk assessment tools to defendants who prosecutors believe won’t show up for their court date or are dangers to the community.

In May, Philadelphia DA Larry Krasner and Chief Public Defender Keir Bradford-Grey withdrew their support for the city’s locally developed risk assessment tool, which they said relied on “stale” data and lacked transparency about how risk scores were calculated.

Sassaman said such changes represent a growing understanding that pretrial release should be the default option for the vast majority of people. “What we are guaranteed by the United States Constitution is a truly individualized look at our humanity and at the circumstances of what put us in the situation of being charged with a crime,” Sassaman said. “If we can find ways to clear entire segments of the population out of the system … then we’ll be able to unwind a lot of its harms.”