How a D.C. Lawmaker is Challenging the Racist Roots of Prison Voting Restrictions

Right now, only the whitest states—Maine and Vermont—allow prisoners to vote. Washington, D.C., could change that.

Kareem McCraney has never voted. The 39-year-old Washington, D.C., resident was arrested when he was 17 and spent 21 years in various federal prisons across the country before he was released last year.

When he was convicted, D.C. law allowed prosecutors to charge him as an adult. The irony isn’t lost on him.

“You charged me as an adult, but I never got to participate in any of these processes as an adult,” he told The Appeal, explaining that he has never had the chance to influence policy or politics.

Most U.S. states and D.C. prohibit people from voting if they are serving time in prison for felonies. But the city disenfranchises an outsize number of people because it has a higher incarceration rate than any state in the country. More than 4,500 of its residents are incarcerated in federal prisons, and over 90 percent of them are Black.

Last week, D.C. Councilmember Robert C. White Jr. introduced the Restore the Vote Amendment Act of 2019, a bill that would make the city the first jurisdiction in the country to restore voting rights to people who are incarcerated. Currently, only Maine and Vermont—the country’s two whitest states—allow people to vote from prison.

With just under half of its population African American, if D.C. were a state, it would be the country’s Blackest one. So the new push for voting rights there has special significance. White told The Appeal that “it’s no coincidence” that states with large African American populations often have strict disenfranchisement policies.

“The majority of states and most Southern states,” he said, prohibited incarcerated residents from voting “right around the time that African Americans were getting the right to vote.

That’s why the bill is so important, he said. Not only does it recognize the racist origin of these laws, but it would also change the electorate in one of the most diverse major cities in the country.

White and other advocates for the abolishment of felony disenfranchisement policies say the laws stem from the Jim Crow era. After the Civil War, states with newly freed slaves enacted laws intended to keep incarcerated people from political power. According to the Sentencing Project, by 1869, 29 states had enacted such laws, which continued to be passed and strengthened for decades after. A 2013 study found that the more Black residents in a state, the more likely the state was to pass a strict disenfranchisement law that permanently denied people convicted of crimes the right to vote.

In 1955, before D.C. had home rule and the ability to pass its own laws, the federal government enacted a law to disenfranchise incarcerated residents. White called that bill “an active effort to disenfranchise African Americans.”

Before he was arrested, McCraney said he wasn’t aware of the systemic racism that guides so many of the country’s criminal justice and civil rights policies. His Northeast D.C. community was mostly Black, he told The Appeal, so he was surrounded by people like him.

“I never had the opportunity to really experience direct, one-on-one, overt racism,” he said.

But in the federal prisons where he spent his 20s and 30s, he quickly realized how racism had shaped his life. Roughly two decades into his sentence for first-degree murder, he filed a pro se petition for resentencing under a D.C. law that allows people convicted as children to get a second chance.

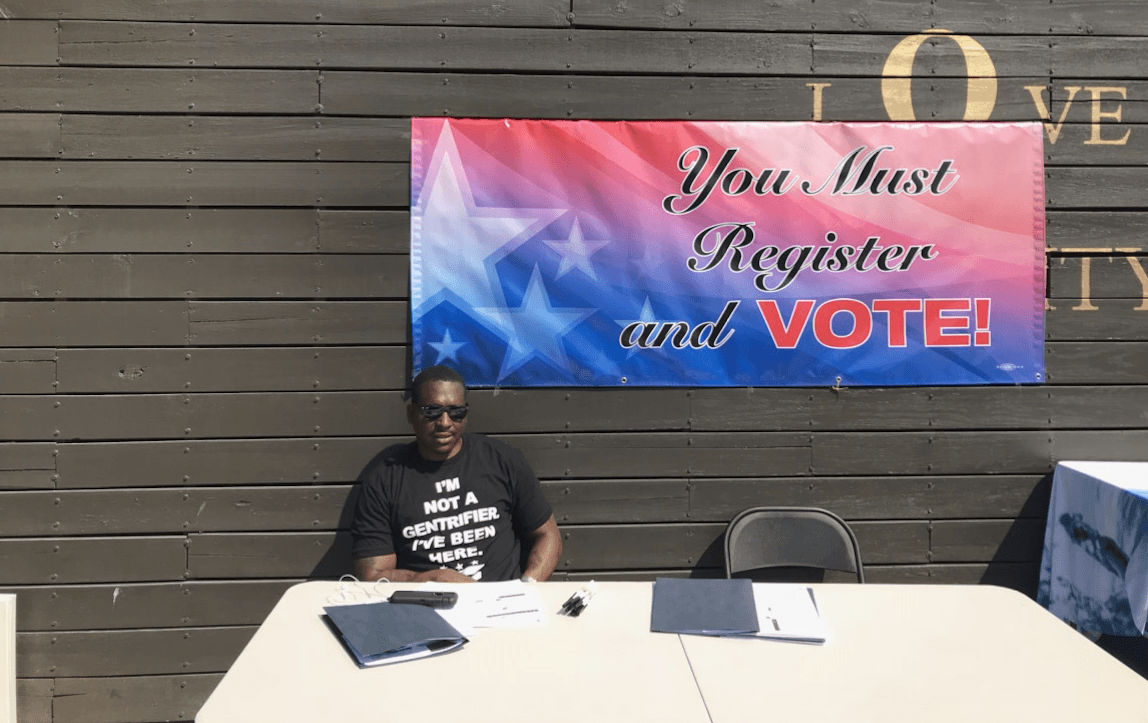

After that was successful, McCraney moved back to Northeast D.C. and worked as a program analyst for the Corrections Information Council. He also became the district’s delegate for the Democratic Caucus for Returning Citizens, and as part of that job, talked with community leaders about the potential to restore voting rights to people who are incarcerated.

It’s a crucial demand and a reasonable one, he said, because there is nothing in the U.S. Constitution prohibiting people convicted of felonies from voting. “All of us who feel like we don’t have a voice—that would give us a voice to push an agenda.”

McCraney was at the table when White met with stakeholders and community groups to discuss the proposal this year. The meeting coincidentally came on the heels of a 2020 presidential candidates forum that aired on CNN in April, where the contenders were asked about the potential for people to vote while incarcerated, sparking a national debate.

Senator Bernie Sanders, who represents Vermont, was the first to say that he thinks all incarcerated people should be allowed to vote. “If you are an American citizen, whether you’re rich, whether you’re poor, whether you’re Black, whether you’re white, whether you are a really wonderful person or not such a nice person, but because you are an American citizen you have the inalienable right to vote,” he told The Appeal: Political Report soon after. A few other Democratic candidates said they would consider the same position, while others, including Beto O’Rourke and Pete Buttigieg, came down against it.

Around that time, dozens of civil rights organizations wrote a letter to the candidates urging them all to consider joining Sanders in his support for abolishing disenfranchisement.

“Felony disenfranchisement is not just anti-democratic and bad for public safety, it is an unpopular practice that sprang from the most shameful era of American history, a vestige of our past wildly out of step with international norms,” the letter said. “And now is the moment for its abandonment.”

Though he was encouraged by those like Sanders who were open to a substantial change, White said he was also “nervous” that the national conversation about voting while incarcerated happened before he could introduce his bill—which had been in the works since he became chairperson of a committee that oversees D.C.’s Commission on Re-Entry and Returning Citizen Affairs.

“At first blush, this issue hits people wrong sometimes, and so it requires a more detailed understanding of history and constitutional rights and rights of citizenship,” he said. “I would have preferred to be able to frame it before there was a national conversation, but the national conversation allowed me to pick up on the strongest opposition arguments and really dissect those arguments.”

Part of the problem, he said, was the inclination for so many to shape the debate around the worst-case examples, like the Boston Marathon bomber, who was cited in the original CNN question to the candidates about voting rights for people in prison.

“Any time you have to jump to the extreme to make a point, you are making less of an argument and more inciting a reaction,” he said.

Amani Sawari, national coordinator for the Right 2 Vote campaign, told The Appeal that the effort in D.C. is exciting because it has been able to “transcend all the negative comments” and send its own positive message.

“When we incorporate [incarcerated people] politically, especially in the most incarceration-heavy area of our country, then we’re saying something different about the value of our incarcerated citizens,” she said.

Every member of the D.C. Council has already agreed to co-introduce White’s bill, making him confident that he can get it passed in the next six to nine months. Mayor Muriel Bowser has not yet indicated if she would sign it and did not respond to requests for comment, but Attorney General Karl Racine has indicated his support.

In many other states, Republican lawmakers have opposed efforts to lift disenfranchisement laws. Many advocates suspect that’s because the new voters—disproportionately people of color—are more likely to vote for Democrats. Washington, D.C., however, is a largely Democratic city and is unlikely to see that kind of opposition. But as with all legislation in D.C., Congress would have the ability to veto the bill before it becomes law.

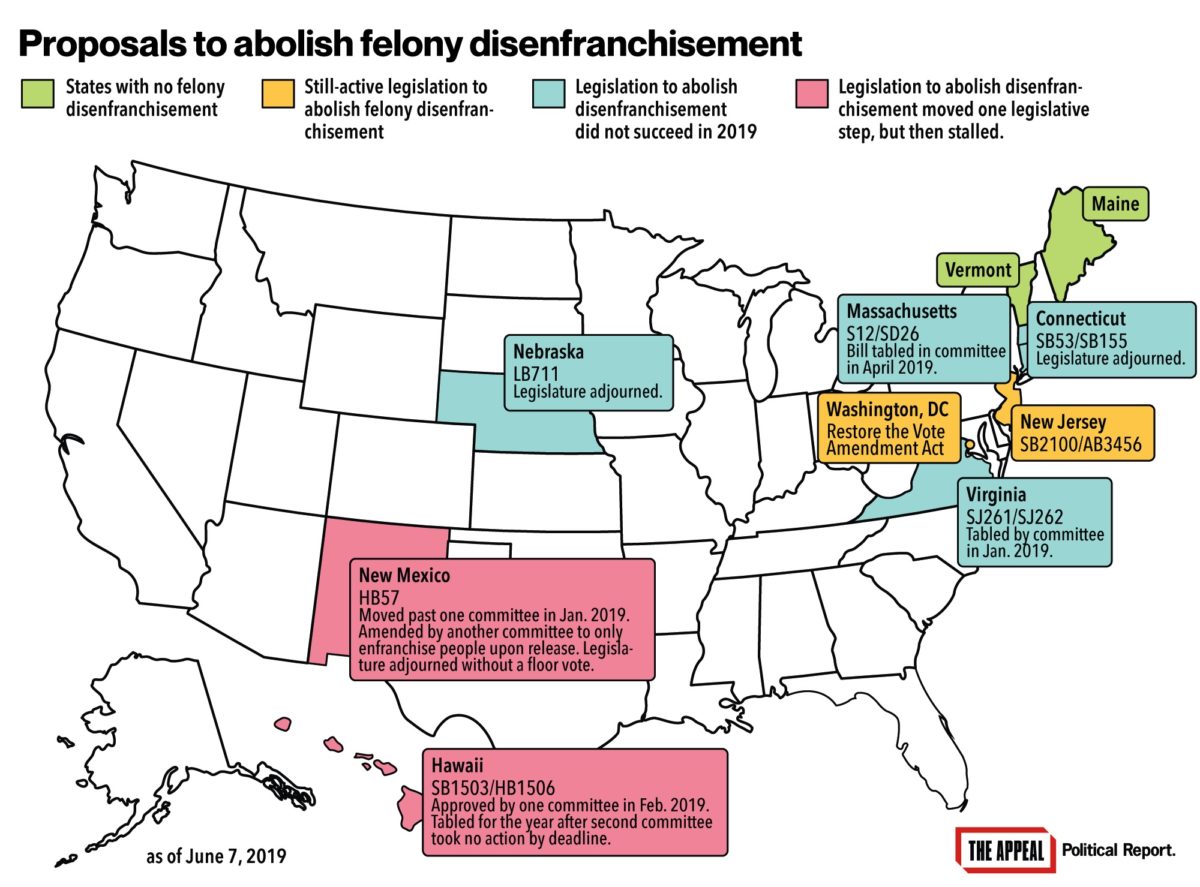

Since last year, bills to allow people to vote while incarcerated have also been introduced in at least seven states. The proposals did not succeed in Nebraska, Virginia, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. Legislative committees passed proposals in Hawaii and New Mexico, but they ultimately stalled. In Massachusetts, organizers are pushing for a popular initiative that would have the same effect.

And some states have chipped away at their strict disenfranchisement policies— like Florida, where voters in November restored civil rights to most people who have completed their sentences.

White said he is hopeful that if the proposal were to pass in D.C., it could set an example for states about the importance of extending civil rights to all citizens.

“People who are incarcerated, the vast majority of them are going to come home,” White said. “We have to make sure that we have policies and programs in place to support them.”

If it were to pass, he said, politicians would be forced to consider policies that are important to incarcerated people—like prison conditions and the use of solitary confinement.

“People who don’t have the right to vote generally have their needs ignored, and that’s something we see in our prison systems,” he said.

McCraney agreed, saying that politicians will no longer be able to “sweep under the rug” the concerns of people serving time for felonies. If they do, he said, “that’s a whole lot of votes that you’re going to miss out on.”